The traditional drop cake (also called drop biscuit) was a popular historic treat in America copied from Europe. However, somehow in America the act of baking a common and popular British drop cake with common and popular chocolate turned into a fancy narrative about how chocolate chip cookies had just been “invented” by a woman in 1938.

Is the invention story true? Are they even American?

Let’s start by scanning through the typical drop cake recipes that can easily be found in the first recipe book publications in English:

- 1883: Ice-cream and Cakes: A New Collection

- 1875: Cookery from Experience: A Practical Guide for Housekeepers

- 1855: The Practical American Cook Book

- 1824: A New System of Domestic Cookery

- 1792: The London Art of Cookery

- 1765: The art of cookery, made plain and easy

Now let’s see the results of such recipes. Thanks to a modern baker who experimented with a 1846 “Miss Beecher’s Domestic Recipe Book” version of drop cake, here we have a picture.

Raisins added would have meant this would be a fruit drop cake (or a fruit drop biscuit). There were many variations possible and encouraged based on different ingredients such as rye, nuts, butter or even chocolate.

Here’s an even better photo to show drop cakes. It’s from a modern food historian who references the 1824 “A New System of Domestic Cookery” recipe for something called a rout cake (rout is from French route, which used to mean a small party or social event).

That photo really looks like a bunch of chocolate chip cookies, right? This food historian even says that herself by explaining “…[traditional English] rout cakes are usually a drop biscuit (cookie)…”.

Cakes are cookies. Got it.

This illustrates quickly how England has for a very long time had “tea cakes with currants”, which also were called biscuits (cookies), and so when you look at them with American eyes you would rightfully think you are seeing chocolate chip cookies. But they’re little cakes in Britain.

More to the point, the American word cookie was derived from the Dutch word koek, which means… wait for it… cake, which also turns into the word koekje (little cake):

Dutcheen koekje van eigen deeg krijgen = a little cake of your own dough (literal) = a taste of your own medicine (figurative)

So the words cake, biscuit and cookie all can refer to basically the same thing, depending on what flavor of English you are using at the time.

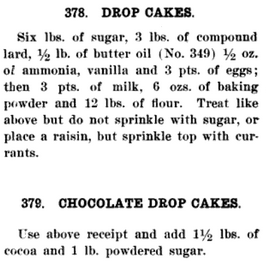

Expanding now on the above 1855 recipe book reference, we also see exactly what is involved in baking a drop cake/koekje/cookie:

DROP CAKES: Take three eggs, leaving out one white. Beat them in a pint bowl, just enough. Then fill the bowl even full of milk and stir in enough flour to make a thick, but not stiff batter. Bake in earthen cups, in a quick oven. This is an excellent recipe, and the just enough beating for eggs can only be determined by experience.

DROP CAKES. Take one quart of flour; five eggs; three fourths of a pint of milk and one fourth of cream, with a large spoonful of sifted sugar; a tea-spoon of salt. Mix these well together. If the cream should be sour, add a little saleratus. If all milk is used, melt a dessert-spoonful of butter in the milk. To be baked in cups, in the oven, thirty to forty minutes.

I used the word “exactly” to introduce this recipe because I found it so amusing to read the phrase “just enough” in baking instructions.

Imagine a whole recipe book that says use just enough the right ingredients, mix just enough and then bake just enough. Done. That would be funny, as that’s the exact opposite of how the very exact science of modern baking works.

Bakers are like chemists, with extremely precise planning and actions.

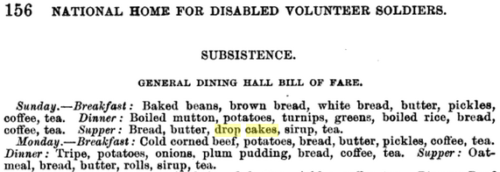

And finally just to set some context for how common it became in America to eat the once-aristocratic drop cakes, here’s the 1897 supper menu in the “General Dining Hall Bill of Fare” from the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers:

Back to the question of chocolate chip cookies versus drop cake, and given all the current worry about disinformation, a story researched on Mental Floss explains that a myth has been created around someone making “Butter Drop Do” and inventing cookies because she accidentally used a “wrong” type of chocolate.

The traditional tale holds that Toll House Inn owner Ruth Wakefield invented the cookie when she ran out of baker’s chocolate, a necessary ingredient for her popular Butter Drop Do cookies (which she often paired with ice cream—these cookies were never meant to be the main event), and tried to substitute some chopped up semi-sweet chocolate instead. The chocolate was originally in the form of a Nestle bar that was a gift from Andrew Nestle himself—talk about an unlikely origin story! The semi-sweet chunks didn’t melt like baker’s chocolate, however, and though they kept their general shape (you know, chunky), they softened up for maximum tastiness. (There’s a whole other story that imagines that Wakefield ran out of nuts for a recipe, replacing them with the chocolate chunks.)

There are three problems with this story.

One, saying “butter drop do cookies” is like saying butter cake do little cakes. That’s hard on the ears. I mean “butter drop do” seems to be some kind of a misprint or a badly scanned script.

This very uniquely named recipe can be found under a cakes category in the 1796 American Cookery book (and don’t forget many drop cake recipe books in England pre-dated this one by decades).

Butter drop do .

No. 3. Rub one quarter of a pound butter, one pound sugar, sprinkled with mace, into one pound and a quarter flour, add four eggs, one glass rose water, bake as No. 1.

The butter drop cake (do?) here appears to be an import of English aristocratic food traditions, which I’ve written about before (e.g. eggnog). But what’s really interesting is this American Cookery book in 1796 is how actual cookie recipes can be found and are completely different from the drop cake (do?) one:

Cookies.

One pound sugar boiled slowly in half pint water, scum well and cool, add two tea spoons pearl ash dissolved in milk, then two and half pounds flour, rub in 4 ounces butter, and two large spoons of finely powdered coriander seed, wet with above; make roles half an inch thick and cut to the shape you please; bake fifteen or twenty minutes in a slack oven–good three weeks.

And that recipe using pearl ash (early version of baking powder) is followed by “Another Christmas Cookey”. So if someone was knowingly following the butter drop cake (do?) recipe instead, they also knew it was explicitly not called a cookie by the author.

Someone needs to explain why the chocolate chip cookie “inventor” was very carefully following a specific cake/koekje recipe instead of a cookie one yet called her “invention” a cookie.

Two, chocolate chips in a drop cake appear almost exactly like drop cakes have looked for a century, with chips or chunks of sweets added. How inventive is it really to use the popular chocolate in the popular cake and call it a cookie?

Three, as Mental Floss points out, the baker knew exactly what she was doing when she put chocolate in her drop cakes and there was nothing accidental.

The problem with the classic Toll House myth is that it doesn’t mention that Wakefield was an experienced and trained cook—one not likely to simply run out of things, let accidents happen in her kitchen, or randomly try something out just to see if it would end up with a tasty result. As author Carolyn Wyman posits in her Great American Chocolate Chip Cookie Book, Wakefield most likely knew exactly what she was doing…

She was doing what had been done many times before, adding a sweet flavor to a drop cake, but she somehow then confusingly marketed it a chocolate chip cookie. I mean she came up with a recipe sure, but did she really invent something extraordinary?

Food for thought: is the chocolate chip cookie really just Americans copying unhealthy European habits (i.e. tipping) to play new world aristocrats instead of truly making something new and better?

What about the chocolate chip itself? Wasn’t that at least novel as a replacement for the more traditional small pieces of sweet fruit? Not really. The chocolate bar, which precipitated the chips, has been credited in 1847 to a British company started by Joseph Storrs Fry.

Thus it seems strange to say that an American putting a British innovation (chocolate bar chips) into a British innovation (drop cake/biscuit/cookie) is an American invention, as much as it is Americans copying and trying to be more like the British.

The earliest recipe I’ve found that might explain chocolate chip cookies is from 1912 (20 years before claims of invention) in “The Twentieth Century Book for the Progressive Baker, Confectioner, Ornamenter and Ice Cream Maker: The Most Up-to-date and Practical Book of Its Kind” by Fritz Ludwig Gienandt.

Important insights come from reading “

Important insights come from reading “