I used to fly five days a week or more before COVID. Now I probably fly less than five days a year. The improvement to my quality of life is wonderful. And in case you needed another reason to skip your next jet…

Airbus has just issued an emergency directive affecting over 6,000 A320 aircraft worldwide, the most flown commercial aircraft on Earth.

Flight Control Data Integrity Breach

The trigger event for investigation was a JetBlue flight on October 30 that pitched violently downward without pilot input, injuring a dozen passengers during the pitch-down (the remainder of the flight was classified as uneventful).

The physics is well understood, and this type of issue has happened before. So why did it happen again, and why is it such a big recall?

New Airbus software created an old data integrity vulnerability.

While solar radiation has remained predictably dangerous, a specific software change removed needed integrity controls, as transistor shrinkage increased risks, and release tests clearly weren’t being done thoroughly enough.

Particle Attack

At usual cruising altitudes (35,000-40,000 feet), an aircraft operates with roughly 100 to 300 times the cosmic ray and solar particle flux we experience at ground level. The Earth’s atmosphere shields from this radiation, so commercial aviation loses a significant portion of protection.

During a solar flare, the sun ejects high-energy protons that travel at nearly the speed of light. When these particles (or the secondary neutrons created when they collide with atmospheric molecules) pass through a semiconductor, they can deposit enough electrical charge to flip a bit in memory or logic circuits (0 becomes a 1, or vice versa). This is a known phenomenon called the Single Event Upset (SEU).

The Airbus advisory traces the exact vulnerability to their ELAC B (Elevator Aileron Computer) hardware running software version L104, the upgrade from L103. Flight control computers process sensor inputs and compute control surface positions many times per second. When a bit flip corrupts a value mid-calculation, such as an elevator deflection command, the output can be wrong without any error-checks.

It is notable in the recall that rolling back to earlier software fixes the Airbus problem. This suggests more robust error detection was reduced, or a vulnerable code path was introduced, or tighter bounds checking was lost that used to reject corrupted values rather than acting on them.

The Precedents

The most famous case is Qantas Flight 72 in October 2008. An A330 cruising at 37,000 feet over Western Australia experienced two sudden, uncommanded pitch-down maneuvers that injured 119 people, 12 seriously. The Australian Transport Safety Bureau investigation examined multiple causes, including the possibility that cosmic rays caused bit flips in one of the aircraft’s Air Data Inertial Reference Units.

The ATSB concluded that the incident:

…occurred due to the combination of a design limitation in the FCPC software of the Airbus A330/A340, and a failure mode affecting one of the aircraft’s three ADIRUs.

The software couldn’t properly handle multiple erroneous data spikes arriving 1.2 seconds apart—a scenario that had never been envisioned during development, despite extensive safety assessment processes.

Critically, investigators declared:

…only known example where this design limitation led to a pitch-down command in over 28 million flight hours on A330/A340 aircraft.

The ADIRU failure mode itself had occurred only three times in over 128 million hours of unit operation. The investigation explicitly examined “secondary high-energy particles generated by cosmic rays that can cause a bit flip” as a potential trigger, though a definitive root cause could not be established.

A similar ADIRU event occurred on another Qantas A330 just weeks later, in December 2008. This time, the crew used revised procedures Airbus issued after QF72 and shut down the affected unit, preventing any data integrity breach.

The radiation vulnerability in software isn’t limited to Airbus. Boeing 737 MAX Cosmic Ray Testing quietly slipped under most people’s radar.

During recertification, following the two very high profile fatal crashes, regulators conducted tests specifically designed to simulate cosmic ray bit flips. According to reporting by the Seattle Times in August 2019, tests that flipped bits in the memory of the MAX’s flight control computers caused pilots to lose control of a simulated aircraft during ground exercises.

The tests focused on flipping five bits controlling the most crucial parameters: positioning of flight controls and activation state of flight control systems, including the infamous MCAS anti-stall system.

What makes this particularly striking is the 737’s flight control architecture seems to have exploited a loophole. The aircraft has two flight control computers, but until the post-crash redesign, they never cross-checked each other’s operation. Each “redundant” channel operated as a single non-redundant channel. The system simply alternated which computer was “master” after each flight. If the active computer produced a bad output, there was no second computer validating it in real time.

This architecture dated back to the mechanical 737-300 in the 1980s and persisted through the computerized MAX. Why was this allowed? The 737’s type certificate traces back to 1967, and the FAA’s “Changed Product Rule” permits derivative aircraft to be certified partially under the original requirements rather than current standards, provided someone argues the changes don’t “materially affect” areas already approved. Boeing positioned the materially different MAX as a derivative of the 737NG rather than a new aircraft type. This preserved pilot type ratings (a major selling point to airlines) because certain legacy design decisions carried forward, but it also obscured vulnerabilities.

The contrast with newer designs is stark. The Boeing 777 uses a triplex architecture with three flight control computers running on different processor architectures. A microcode flaw or radiation-induced error in one processor type won’t affect all three simultaneously. Airbus fly-by-wire aircraft use dual cross-checking between redundant systems, which clearly have weaknesses and gaps.

Boeing’s MCAS compounded their integrity flaws; it relied on a single angle-of-attack sensor with no cross-check, had virtually unlimited authority to move the stabilizer, and could activate repeatedly. When that sensor failed on Lion Air 610 and Ethiopian 302, the system did exactly what it was programmed to do, with fatal results. A former Boeing engineer told the Seattle Times:

A single point of failure is an absolute no-no. That is just a huge system engineering oversight.

The recertified MAX now uses both flight control computers with cross-checking, compares both AOA sensors, limits MCAS to a single activation per event, and disables the system entirely if the sensors disagree. These are the redundancy features that should have been there from the start.

Modern Systems, More Vulnerable

The physics cuts against us as transistors shrink. In 1979, when IBM researchers first described the mechanism for cosmic ray-induced upsets, transistors were measured in micrometers. Today they’re measured in nanometers—a thousand times smaller. Smaller transistors require less charge to flip a bit. The same particle that would have been harmless in 1979 can now corrupt modern chips.

Robust safety-critical systems typically defend against SEUs through redundancy and voting (multiple computers cross-checking each other), error-correcting memory, range checks on computed values (rejecting implausible outputs), and watchdog timers that detect anomalous states.

When these defenses have gaps, such as when a software update inadvertently weakens them, the physical environment starts to matter in ways designers didn’t adequately anticipate.

An IEEE paper by Taber and Normand established this in 1992:

…typical non-radiation-hardened 64K and 256K static random access memories can experience a significant soft upset rate at aircraft altitudes due to energetic neutrons created by cosmic ray interactions in the atmosphere.

Their recommendation:

…error detection and correction circuitry be considered for all avionics designs containing large amounts of semiconductor memory.

Here we are, three decades later.

What Happens Next

The immediate disruption is significant: a three-hour maintenance action per aircraft during the Thanksgiving travel period, affecting the backbone of global short-haul aviation. The longer-term lesson is that software doesn’t exist in a vacuum. The assumptions at ground level during testing, oriented towards proof of engineering activity, will not provide safe outcomes at 37,000 feet during a geomagnetic storm.

We’re approaching solar maximum in the current 11-year cycle. October 2025 saw elevated solar activity. The timing isn’t coincidental.

Aviation has generally been excellent at learning from incidents. The Qantas 72 investigation led to software changes across the A330/A340 fleet. The 737 MAX recertification exposed radiation vulnerabilities that had gone unexamined. This Airbus directive, inconvenient as it may seem, represents the system working by identifying a vulnerability and addressing it before another catastrophic outcome.

But the pattern is still concerning. Each vulnerability was discovered only after an incident or during extraordinary scrutiny. The question is where remaining gaps exist in systems that haven’t yet been tested by a well-timed wayward solar proton.

Investigations have revealed new software removed protections against radiation-induced bit flips. We still don’t know if that’s exactly what happened on October 30, but Airbus clearly understands the problem with integrity breaches and isn’t waiting to fly around and find out.

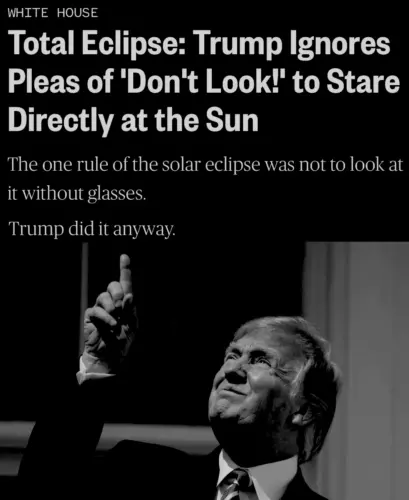

Stop looking at the sun like you don’t know it can kill you.

It is not just solar flares that can cause bit flips. Nuclear in chip packaging causes the same problem.