Lately I often have been asked about cloud counter-measures to rubber-hose risks, and as I begin to explain I get interrupted with “wait, hold on, but why is it called rubber-hose?”

It is a fair question and, as a historian, I am eager to indulge those willing to ask a “how did we get here from there” security question.

Rubber-hose implies a means a type of physical torture used to extract a secret without leaving evidence of torture. Rubber-hose cryptanalysis is rooted (pun not intended) in American traditions of torture to disclose secrets and preserve power.

Physical Torture to Break American Cryptography

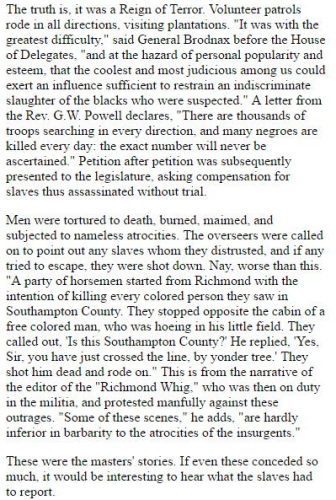

To understand why this phrase is so commonly used in America, we have to remember first that slave rebellions in 1830s led to a reign of brutal white-supremacist terror escalating until they started a full Civil War in 1861.

New York abolished slavery in 1827, around the time many countries around the world were doing the same. Abolition and/or laws prohibiting slavery spread quickly:

1824 – Mexico

1831 – Bolivia

1833 – British Empire (led by Mary Prince, an escaped slave from Bermuda)

1835 – France

1836 – Portugal

An important footnote here is that the Mexican abolitionist movement greatly angered white immigrants to Mexico. These settlers to the “wild” Texas territory demanded they be allowed to keep slaves.

This came to a head at the Alamo in 1836 when violent secession formed a new nation for slavery. That is right, every time you hear someone say “Remember the Alamo” think of white supremacists expressing pride at preserving slavery while globally it was condemned.

This fits a pattern more widespread, that between 1831 and 1861 many US slaveholders thought a “reign of terror” was their best method of preserving white power.

In case you are wondering, encryption was very present in America during the next 30 years, and needed key management that could withstand physical torture by those who did not want slavery to end.

Had the US not declared independence from the King of England, slavery arguably would have ended in the US by 1834 if not earlier (colony of Georgia abolished slavery in 1735, colony of Vermont abolished slavery in 1777… revolution and independence restarted slavery).

Alas, this was not to be the case under a pro-slavery President Jackson who had been elected in 1828. By 1835, around the time of Texas seceding to preserve slavery, Jackson was harshly criminalizing speech in order to prevent even the discussion of abolition (his federal Postmaster General Kendall called it his patriotic duty to illegally intercept, inspect and destroy US mail).

Black Americans who stepped off a ship found with a copy of 1829 Walker’s Appeal were thrown in jail and subjected to surveillance, if not tortured, as though they were a threat to the white police states of the South.

As you can imagine, encryption becomes very useful for those working towards freedom under a white supremacist President inspecting all written materials in the mail.

The punishment for anyone discussing abolition was severe. Abraham Lincoln famously gave a speech in 1838 condemning the surveillance and torture methods used upon Americans who believed in the kind of freedom found in other nations:

Thus went on this process of hanging, from gamblers to negroes, from negroes to white citizens, and from these to strangers; till, dead men were seen literally dangling from the boughs of trees upon every road side; and in numbers almost sufficient, to rival the native Spanish moss of the country, as a drapery of the forest.

Turn, then, to that horror-striking scene at St. Louis. A single victim was only sacrificed there. His story is very short; and is, perhaps, the most highly tragic, of any thing of its length, that has ever been witnessed in real life. A mulatto man, by the name of McIntosh, was seized in the street, dragged to the suburbs of the city, chained to a tree, and actually burned to death; and all within a single hour from the time he had been a freeman, attending to his own business, and at peace with the world.

Such are the effects of mob law; and such are the scenes, becoming more and more frequent in this land so lately famed for love of law and order; and the stories of which, have even now grown too familiar, to attract any thing more, than an idle remark.

Sadly a great many Americans, from large plantation owner to poor white laborers, aspired to dreams of sudden wealth by harming others. America, long after the rest of the world was moving in a better direction, continued to think of an expansion of slavery practices as their get-rich-quick scheme.

Certain American men, as well as their enablers, kept arguing that the Constitution “enriched” whites by giving them the exclusive right to torture and murder without penalty as long as they were preserving their right to leisure time and preference for avoiding work by playing golf instead. There is a simple reason why many golf courses to this day market themselves by highlighting pro-slavery terrorists:

When Southwick G.C. in Graham, North Carolina first opened in 1969, it was known as Confederate Acres G.C. for no apparent reason other than to appeal to golfers who might be [pro-slavery].

Mountaintop G. & Lake C. in Cashiers, North Carolina one of the newest members of America’s 100 Greatest Golf Courses, has in its clubhouse suites named in honor of Confederate generals such as Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and Turner Ashby, all of whom fought [to preserve slavery] alongside early Cashiers resident General Wade Hampton

Yes, golf courses around America are out in the open about being pro-slavery, as if it is comforting to golfers if they can celebrate men who tortured and murdered Americans to enrich themselves. But I digress…

Managing secrets in the 1840s context of Americans surviving torture and murder by violent pro-slavery militants, even Edgar Allen Poe by 1843 entered the fray, publishing instructions in a story set in South Carolina to help increase the use of cryptograms. It was his most popular story during his lifetime.

In 1844 former-President Adams won an eight-year long campaign in the House of Representatives and overturned the Jacksonian bans on free speech, but torture and murder by pro-slavery terrorists continued to rise. Although Texas agreed to annexation by the US in 1845 they came with the stated hard requirement that slavery remain legal (foreshadowing their second secession, remembering the Alamo by declaring a war on abolitionists again in 1861).

It was because John Brown witnessed the wholesale torture and murder of abolitionists at this time that he became compelled to answer with force the literally burning question “are we free or are we slaves under Southern mob law?” His forceful attempts ended with his execution in 1859. And his demise was thought by slaveholders in 1860 as a great victory; sort of a proof at the highest federal levels that brutally murdering abolitionists and slaves carried no consequences, while resistance to slavery would continue to be fatal.

And yet the situation worsened further, with abolition demands of course growing. By 1861 the white mobs who had for three decades been torturing and murdering fellow Americans raised their violence even further and declared an all-out war to preserve slavery.

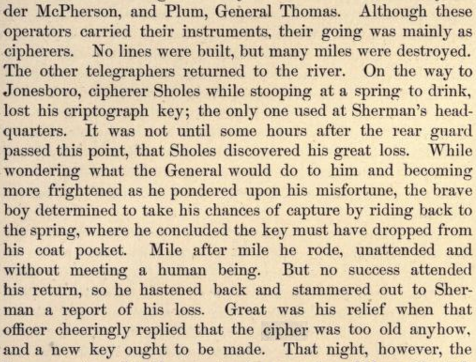

At this point I just want to mention key management in American history continues to be documented. Now it is soldiers in the US Army talking about fighting to preserve the Union, deploying encryption that has to withstand attacks by people who would torture anyone just to continue slavery practices.

Here’s an example from “The Military Telegraph During the Civil War in the United States: an Exposition of Ancient and Modern Means of Communication, and of the Federal and Confederate Cipher System” by code-breaker Captain William R. Plum

Fast Forward to the Rubber Hose Years

With the 1860s encryption in mind, we need to skip 100 years ahead to the 1960s. The American south still had white supremacists infiltrating departments of authority such as the police as a means to perpetuate their unjust power over non-whites, through violent means including torture.

Freedom riders gives a good snapshot of the situation at hand (no pun intended):

Freedom Riders is the powerful harrowing and ultimately inspirational story of six months in 1961 that changed America forever. From May until November 1961, more than 400 black and white Americans risked their lives—and many endured savage beatings and imprisonment—for simply traveling together on buses and trains as they journeyed through the Deep South. Deliberately violating Jim Crow laws in order to test and challenge a segregated interstate travel system, the Freedom Riders met with bitter racism and mob violence along the way, sorely testing their belief in nonviolent activism.

Those savage beatings were with rubber-hoses, as well as with phone-books and other soft materials that caused maximum pain with minimum evidence.

Cyber-security-historian protip: we won’t ever say phone-book cryptanalysis to refer to physical torture methods because that becomes confused with logical brute force techniques (use of the contents of a phonebook to reveal secrets).

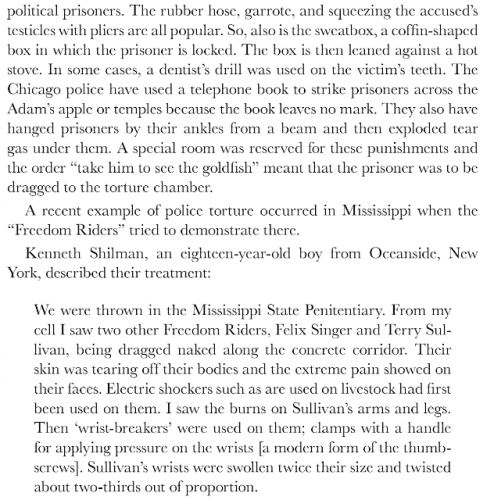

Thus one can read about torture techniques used by white supremacists during the 1950s and find exact reference to the rubber hose method as a subset of “third degree” questioning.

For example, in a History of Torture text, you can read about US police methods used to force confessions and reveal secrets:

Another example to consider is Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge who from 1972 to 1991 led what he called a “Midnight Crew” to systematically torture 100 black men and women into false confessions. Many served decades in prison for crimes they did not commit, while at least 10 were sent to death row.

Think about the circumstances for someone like Madison Hobley in 1987. He lost his wife and son in an apartment fire. Burge’s men soon after brutally tortured him until they said he confessed to murdering his own family. Hobley, sentenced to death, received a pardon only sixteen years later in 2003 after it became abundantly clear how police lied and planted false evidence. The entire case that sent him to death row was false, even beyond the torture he underwent right after his family died in a tragic fire.

There you have it. The rubber hose is a political tool of American power that has commonly used in attempts to claim access to secrets through excessive means without being held accountable.

Cryptography withstanding a rubber-hose really refers to politics of torture in America from the mid-1800s resurfacing in the mid-1900s related to rubber being a more common and inexpensive material.

Bringing It Back to Cryptanalysis Today

This is not just about the past, unfortunately, as I implied at the start of this post. People considering cloud computing are asking daily lately about the rubber-hose. There still is a real threat of torture. World Affairs vividly explains this situation in a political analysis of American traditions:

Decent people and decent countries do not engage in [torture] under any circumstances, whatever the consequences, and that’s really all there is to it.

[…]

Ideals are one thing, the reality of American history quite another. There is, in fact, a well-established American tradition of torture. The definitive text on it is Torture and Democracy by Darius Rejali, himself an opponent of torture. He sees “a long, unbroken, though largely forgotten history of torture in democracies at home and abroad.” What the torture techniques of democracies have in common is that they leave no lasting marks on the victims, no proof. Rejali calls this “clean torture.”

Electroshock began in democracies, and it was in the United States that interrogators first used rubber hoses to administer beatings that left no bruises. Sleep deprivation and stress positions (the “third degree”) were once common practices of American police.

It’s not only the police who have tortured or used other harsh methods. The U.S. military has, too. During the war in the Philippines at the beginning of the twentieth century, American troops employed the “water cure,” a forerunner of waterboarding. During the Vietnam War, torture was probably even more extensive. Whatever its professed ideals, the United States has tortured in the past. It has tortured in the near-present. And should needs arise and circumstances dictate, it will probably torture in the future.

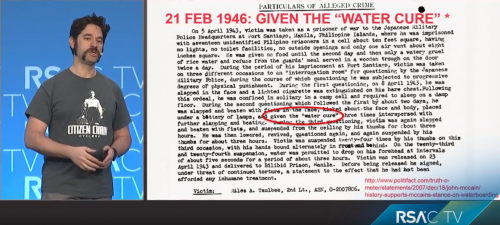

My only addition to this analysis is that “water cure” was treated as a war crime by the US and cited in its court cases against the Japanese during WWII. I spoke about this in my RSAC presentation “Security Humanitarianism: Extraordinary Examples of Tech Improving Lives”

It is a sad footnote to history that war crime cases before 1945 and prosecuted in 1946 were sealed after WWII and the US then began engaging in the exact practices they earlier had argued were a clear violation of human rights. As the quote above warns: “ideals are one thing, the reality of American history are quite another.”

If you seek a more contemporary example, November 2003 was when the US Army tortured to death an Iraq army general who had served under Saddam Hussein. General Abed Hamed Mowhoush died aged 56, beaten and then suffocated to death by Americans using methods including a rubber hose to forcibly extract secrets. Case details were revealed in 2005 court-martial proceedings for two men, without getting into details of government agencies giving orders.

Conclusion

Rubber-hose cryptanalysis is rooted (pun not intended) in American traditions of torture to disclose secrets and preserve power. Despite white supremacists losing their war of aggression against own country, their history of torture methods still seems nowhere near being abolished. And perhaps most dangerously, despite being proven ineffective, some groups may still see themselves as maintaining or gaining power with old “reign of terror” practices.

Hopefully now you can see how we got here from there. This is why when helping with key management solutions for cloud workloads running in America, I increasingly hear requests from people to discuss models that address threats like rubber-hose cryptanalysis techniques.