Next time you bang on a vending machine for a bottle that refuses to fall into your hands, ask yourself if restaurants soon will have only robots serving you meals.

Next time you bang on a vending machine for a bottle that refuses to fall into your hands, ask yourself if restaurants soon will have only robots serving you meals.

Maybe it’s true there is no future for humans in service industries. Go ahead, list them all in your head. Maybe problems robots have with simple tasks like dropping a drink into your hands are the rare exceptions and the few successes will become the norm instead.

One can see why it’s tempting to warn humans not to plan on expertise in “simple” tasks like serving meals or tending a bar…take the smallest machine successes and extrapolate into great future theories of massive gains and no execution flaws or economics gone awry.

Just look at cleaning, sewing and cooking for examples of what will be, how entire fields have been completely automated with humans eliminated…oops, scratch that, I am receiving word from my urban neighbors they all seem to still have humans involved and providing some degree of advanced differentiation.

Maybe we should instead look at darling new startup Blue Apron, turning its back on automation, as it lures millions in investments to hire thousands of humans to generate food boxes. This is such a strange concept of progress and modernity to anyone familiar with TV dinners of the 1960s and the reasons they petered out.

Blue Apron’s meal kit service has had worker safety problems

Just me or is anyone else suddenly nostalgic for that idyllic future of food automation (everything containerized, nothing blended) as suggested in a 1968 movie called “2001”…we’re 16 years late now and I still get no straw for my fish container?

I don’t even know what that box on the top right is supposed to represent. Maybe 2001 predicted chia seed health drinks.

Speaking of cleaning, sewing and cooking with robots…someone must ask at some point why much of automation has focused on archetypal roles for women in American culture. Could driverless tech be targeting the “soccer-mom” concept along similar lines; could it arguably “liberate” women from a service desired from patriarchal roles?

Hold that thought, because instead right now I hear more discussion about a threat from robots replacing men in the over-romanticized male-dominated group of long-haul truckers. (Protip: women are now fast joining this industry)

Whether measuring accidents, inspections or compliance issues, women drivers are outperforming males, according to Werner Enterprises Inc. Chief Operating Officer Derek Leathers. He expects women to make up about 10 percent of the freight hauler’s 9,000 drivers by year’s end. That’s almost twice the national average.

The question is whether American daily drivers, of which many are professionals in trucks, face machines making them completely redundant just like vending machines eliminating bartenders.

It is very, very tempting to peer inside any industry and make overarching forecasts of how jobs simply could be lost to robots. Driving a truck on the open roads, between straight lines, sounds so robotic already to those who don’t sit in the driver’s seat. Why has this not already been automated, is the question we should be answering rather than how soon will it happen.

Only at face value does driving present a bar so low (pun not intended) machines easily could take it over today. Otto of the 1980 movie “Airplane” fame comes to mind for everyone I’m sure, sitting ready to be, um, “inflated” and take over any truck anywhere to deliver delicious TV dinners.

Yet when scratching at barriers, maybe we find trucking is more complicated than this. Maybe there could be more to human processes, something really intelligent, than meets a non-industry specific robotic advocate’s eye?

Systems that have to learn, true robots of the future, need to understand a totality of environment they will operate within. And this begs the question of “knowledge” about all tasks being replaced, not simply the ones we know of from watching Hollywood interpretations of the job. A common mistake is to underestimate knowledge and predict its replacement with an incomplete checklist of tasks believed to point in the general direction of success.

Once the environmental underestimation mistake is made another mistake is to forecast cost improvements by acceleration of checklists towards a goal of immediate decision capabilities. We have seen this with bank ATMs, which actually cost a lot of money to build and maintain and never achieved replacement of teller decision-trees; even more security risks and fraud were introduced that required humans to develop checklists and perform menial tasks to maintain ATMs, which still haven’t achieved full capability. This arguably means new role creation is the outcome we should expect, mixed with modest or even slow decline of jobs (less than 10% over 10 years).

Automation struggles at eliminating humans completely because of the above two problems (need for common sense and foundations, need for immediate decision capabilities based on those foundations) and that’s before we even get to the need for memory and a need for feedback loops and strategic thinking. The latter two are essential for robots replacing human drivers. Translation to automation brings out nuances in knowledge that humans excel in as well as long-term thoughts both forwards and backwards.

Machines are supposed to move beyond limited data sets and be able to increase minimum viable objectives above human performance, yet this presupposes success at understanding context. Complex streets and dangerous traffic situations are a very high bar to achieve, so high they may never be reached without human principled oversight (e.g. ethics). Without deep knowledge of trucking in its most delicate moments the reality of driver replacement becomes augmentation at best. Unless the “driver” definition changes, goal posts are moved and expectations for machines are measured far below full human capability and environmental possibility, we remain a long way from replacement.

Take for example the amount of time it takes to figure out risk of killing someone in an urban street full of construction, school and loading zones. A human is not operating within a window 10 seconds from impact because they typically aim to identify risks far earlier, avoiding catastrophes born from leaving decisions to last-seconds.

I’m not simply talking about control of the vehicle, incidentally (no pun intended), I also mean decisions about insurance policies and whether to stay and wait for law enforcement to show up. Any driver with rich experience behind the wheel could tell you this and yet some automation advocates still haven’t figured that out, as they emphasize sub-second speed of their machines is all they need/want for making decisions, with no intention to obey human imposed laws (hit-and-run incidents increased more than 40% after Uber was introduced to London, causing 11 deaths and 5,000 injuries per year).

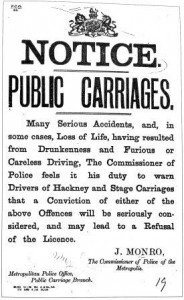

For those interested in history we’re revisiting many of the dilemmas posed the first time robotic idealism (automobiles) brought new threat models to our transit systems. Read a 10 Nov 1832 report on deaths caused by ride share services, for example.

The Inquest Jury found a verdict of man- slaughter against the driver,—a boy under fifteen years of age, and who appeared to have erred more from incapacity than evil design; and gave a deodand of 50/. against the horse and cabriolet, to mark their sense of the gross impropriety of the owner in having in- trusted the vehicle to so young and inexperienced a person.

Young and inexperienced is exactly what even the best “learning” machines are today. Sadly for most of 19th Century London authorities showed remarkably little interest in shared ride driving ability. Tests to protect the public from weak, incapacitated or illogical drivers of “public carriages” started only around 1896.

Young and inexperienced is exactly what even the best “learning” machines are today. Sadly for most of 19th Century London authorities showed remarkably little interest in shared ride driving ability. Tests to protect the public from weak, incapacitated or illogical drivers of “public carriages” started only around 1896.

Finding balance between insider expertise based on experience and outsider novice learner views is the dialogue playing out behind the latest NHTSA automation scales meant to help regulate safety on our roads. People already are asking whether costs to develop systems that can go higher than “level three” (cede control under certain conditions and environments) autonomous vehicle are justified. That third level of automation is what typically is argued by outsiders to be the end of the road for truck drivers (as well as soccer moms).

The easy answer to the third level is no, it still appears to be years before we can SAFELY move above level three and remove humans in common environments (not least of all because hit-and-run murder economics heavily favoring driverless fleets). Cost reductions today through automation make far more sense at the lower ends of the scale where human driver augmentation brings sizable returns and far fewer chances of disaster or backlash. Real cost, human life error, escalates quickly when we push into a full range of even the basic skills necessary to be a safe driver in every environment or any street.

There also is a more complicated answer. By 2013 we saw Canadian trucks linking up in Alberta’s open road and using simple caravan techniques. Repeating methods known for thousands of years, driver fatigue and energy costs were significantly dropped though caravan theory. Like a camel watching the tail of one in front through a sandstorm…. In very limited private environments (e.g. competitions, ranches, mines, amusement parks) the cost of automation is less and the benefits realized early.

I say the answer is complicated because level three autonomous vehicle still must have a human at the controls to take over, and I mean always. The NHTSA has not yet provided any real guidance on what that means in reality. How quickly a human must take-over leaves a giant loophole in defining human presence. Could the driver be sleeping at the controls, watching a movie, or even reposing in the back-seat?

The Interstate system in America has some very long-haul segments with traffic flowing at similar speed with infrequent risk of sudden stop or obstruction. Tesla, in their typically dismissive-of-safety fashion despite (or maybe because of) their cars repeatedly failing and crashing, called major obstructions on highways a “UFO” frequency event.

Cruise control and lane-assist in pre-approved and externally monitored safe-zones in theory could allow drivers to sleep as they operate, significantly reducing travel times. This is a car automation model actually proposed in the 1950s by GM and RCA, predicted to replace drivers by 1974. What would the safe-zone look like? Perhaps one human taking over the responsibility by using technology to link others, like a service or delegation of decision authority, similar to air traffic control (ATC) for planes. Tesla is doing this privately, for those in the know.

Ideally if we care about freedom and privacy, let alone ethics, what we should be talking about for our future is a driver and a co-pilot taking seats in the front truck of a large truck caravan. Instead of six drivers for six trucks, for example, you could find two drivers “at the controls” for six trucks connected by automation technology. This is powerful augmentation for huge cost savings, without losing essential control of nuanced/expert decisions in myriad local environments.

This has three major benefits. First, it helps with the shortage of needed drivers, mentioned above being filled by women. Second it allows robot proponents to gather real-world data with safe open road operations. Third, it opens the possibility of job expansion and transitions for truckers to drone operations.

On the other end of the spectrum from boring unobstructed open roads, in terms of driverless risks, are the suburban and urban hubs (warehouses and loading docks) that manage complicated truck transactions. Real human brain power still is needed for picking up and delivering the final miles unless we re-architect the supply-chain. In a two-driver, six-truck scenario this means after arriving at a hub, trucks return to one driver one truck relationship, like airplanes reaching an airport. Those trucks lacking human drivers at the controls would sit idle in queue or…wait for it…be “remotely” controlled by the locally present human driver. The volume of trucks (read percentage “drones”) would increase significantly as number of drivers needed might actually decline only slightly.

Other situations still requiring human control tend to be bad weather or roads lacking clear lines and markings. Again this would simply mean humans at the controls of a lead vehicle in a caravan. Look at boats or planes again for comparison. Both have had autopilots far longer, at least for decades, and human oversight has yet to be cost-effectively eliminated.

Could autopilot be improved to avoid scenarios that lead to disaster, killing their human passengers? Absolutely. Will someone pay for autopilots to avoid any such scenarios? Hard to predict. For that question it seems planes are where we have the most data to review because we treat their failures (likely due to concentrated loss of life) with such care and concern.

There’s an old saw about Allied bombers of WWII being riddled with bullet holes yet still making it back to base. After much study the Air Force put together a presentation and told a crowded room that armor would be added to all the planes where concentrations of holes were found. A voice in back of the crowd was heard asking “but shouldn’t you put the armor where the holes aren’t? Where are the holes on planes that didn’t come back”.

It is time to focus our investments on collecting and understanding failures to improve driving algorithms of humans, by enhancing the role of drivers. The truck driver already sits on a massively complex array of automation (engines and networks) so adding more doesn’t equate to removing the human completely. Humans still are better at complex situations such as power loss or reversion to manual controls during failures. Automation can make both flat open straight lines into the sunset more enjoyable, as well as the blizzard and frozen surface, but only given no surprises.

Really we need to be talking about enhancing drivers, hauling more over longer distance with fewer interruptions. Beyond reduced fatigue and increased alertness with less strain, until systems move above level three automation the best-case use of automation is still augmentation.

Drivers could use machines for making ethical improvements to their complex logistics of delivery (less emissions, increased fuel efficiency, reduced strain on the environment). If we eliminate drivers in our haste to replace them, we could see fewer benefits and achieve only the lowest-forms of automation, the ones outsiders would be pleased with while those who know better roll their eyes with disappointment.

Or maybe Joe West & the Sinners put it best in their classic trucker tune “$2000 Navajo Rug”

I’ve got my own chakra machine, darlin’,

made out of oil and steel.

And it gives me good karma,

when I’m there behind the wheel