At this year’s ISACA-SF conference I will present how to stop malicious attacks against data mining and machine learning.

First, the title of the talk uses the tag #HeavyD. Let me explain why I think this is more than just a reference to the hiphop artist or nuclear physics.

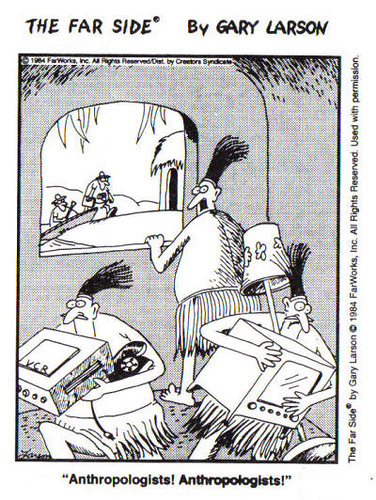

Credit for the term goes to @RSnake and @joshcorman. It came up as we were standing on a boat and bantering about the need for better terms than “Big Data”. At first it was a joke and then I realized we had come upon a more fun way to describe the weight of big data security.

What is weight?

Way back in 2006 Gill gave me a very tiny and light racing life-jacket. I noted it was not USCG Type III certified (65+ newtons). It seemed odd to get race equipment that wasn’t certified, since USCG certification is required to race in US Sailing events. Then I found out the Europeans believe survival of sailors requires about 5 fewer newtons than the US authorities.

Awesome Race Equipment, but Not USCG Approved

That’s a tangent but perhaps it helps frame a new discussion. We think often about controls to protect data sets of a certain size, which implies a measure at rest. Collecting every DB we can and putting it in a central hadoop, that’s large.

If we think about protecting large amounts of data relative to movement then newton units come to mind. Think of measuring “large” in terms of a control or countermeasure — the force required to make one kilogram of mass go faster at a rate of one meter per second:

Hold onto that thought for a minute.

Second, I will present on areas of security research related to improving data quality. I hinted at this on Jul 15 when I tweeted about a quote I saw in darkreading.

argh! no, no, no. GIGO… security researcher claims “the more data that you throw at [data security], the better”.

After a brief discussion with that researcher, @alexcpsec, he suggested instead of calling it a “Twinkies flaw” (my first reaction) we could call it the Hostess Principle. Great idea! I updated it to the Evil Hostess Principle — the more bad ingredients you throw at your stomach, the worse. You are prone to “bad failure” if you don’t watch what you eat.

I said “bad failure” because failure is not always bad. It is vital to understand the difference between a plain “more” approach versus a “healthy” approach to ingestion. Most “secrets of success” stories mention that reaction speed to failure is what differentiates winners from losers. That means our failures can actually have very positive results.

Professional athletes, for example are said to be the quickest at recovery. They learn and react far faster to failure than average. This Honda video interviews people about failure and they say things like: “I like to see the improvement and with racing it is very obvious…you can fail 100 times if you can succeed 1”

So (a) it is important to know the acceptable measure of failure. How much bad data are we able to ingest before we aren’t learning anymore — when do we stop floating? Why is 100:1 the right number?

And (b) an important consideration is how we define “improvement” versus just change. Adding ever more bad data (more weight), as we try to go faster and be lighter, could just be a recipe for disaster.

Given these two, #HeavyD is a presentation meant to explain and explore the many ways attackers are able to defeat highly-scalable systems that were designed to improve. It is a technical look at how we might setup positive failure paths (fail-safe countermeasures) if we intend to dig meaning out of data with untrusted origin.

Who do you trust?

Fast analysis of data could be hampered by slow processes to prepare the data. Using bad data could render analysis useless. Projects I’ve seen lately have added weeks to get source material ready for ingestion; decrease duplication, increase completeness and work towards some ground rule of accurate and present value. Already I’m seeing entire practices and consulting built around data normalization and cleaning.

Not only is this a losing proposition (e.g. we learned this already with SIEM), the very definition of big data makes this type of cleaning effort a curious goal. Access to unbounded volumes with unknown variety at increasing velocity…do you want to budget to “clean” it? Big data and the promise of ingesting raw source material seems antithetical to someone charging for complicated ground-rule routines and large cleaning projects.

So we are searching for a new approach. Better risk management perhaps should be based on finding a measure of data linked to improvement, like Newtons required for a life-jacket or healthy ingredients required from Hostess.

Look forward to seeing you there.