In private circles I was agitating for a while on the humanitarian crisis in North Korea. Although I have collected a bit of data and insights over the years it just hasn’t seemed like the sort of thing people were interested in or asking about. Not exactly good conversation material.

Then earlier this year I was at Bletchley Park and reading about Alan Turing. A quote of his prompted me to post my thoughts here on North Korea’s humanitarian crisis. Turing said basically (paraphrasing)

I helped my country defeat the Nazis, who used chemical castration to torture people including gays and Jews. In 1952 my country wants to give me the same treatment as a form of “managing” gays.

Turing’s life story was not well known until long after he died. And as we learn more about his tragic end it turns out despite exceptional service to his country he was horribly misunderstood and mistreated. He fought to preserve dignity against spurious charges; his social life and personal preferences caused him much trouble with British authorities. Turing was under constant surveillance and driven into horrible despair. After suffering effects of chemical castration, required by a court order, he committed suicide.

I’ll write more about the Turing incident on another post. Suffice it to say here that in the 1950s there was an intense fear-mongering climate against “gay communist” England. Thousands of men were sent to prison or chemically castrated without any reasonable cause.

Between 1945 and 1955 the number of annual prosecutions for homosexual behaviour rose from 800 to 2,500, of whom 1,000 received custodial sentences. Wolfenden found that in 1955 30% of those prosecuted were imprisoned.

The English enacted horrible treatment, even torture, to gay men for what end exactly? Turing was baffled at being arrested for “gross indecency” not least of all because just ten years earlier he had helped his country fight to protect people against such treatment. A gruesome early death was predictable for those monitored and questioned by police, even without charges.

The reform activist Antony Grey quotes the case of police enquiries in Evesham in 1956, which were followed by one man gassing himself, one throwing himself under a train, leaving widow and children, and an 81 year old dying of a stroke before sentence could be passed.

Why do I mention this? Think about the heavily politicized reports written by Mandiant or Crowdstrike. We see China, Russia and Iran accused of terrible things as if we only should look elsewhere for harm. If you are working for one of these companies today and do not think it possible things you care about abroad could happen at home, this post is for you. I recommend you consider how Turing felt betrayed by the country he helped defend.

Given Turing’s suffering can we think more universally, more forward? Wouldn’t that serve to improve moral high-ground and justifications for our actions?

Americans looking at North Korea often say they are shocked and saddened about treatment of prisoners there. I’ll give a quick example. Years ago in a Palo Alto, California a colleague recommended a book he had just finished. He said it proved without a doubt how horrible communism fails and causes starvation, unlike our capitalism that brings joy and abundance. The obvious touch of naive free-market fervor was bleeding through so I questioned whether we should trust single-source defection stories. I asked how we might verify such data when access was closed.

I ran straight into the shock and disgust of someone as if I were excusing torture, or justifying famine. How dare I question accusations about communism, the root of evil? How dare I doubt the testimony of an escapee who suffered so much to bring us truth about immorality behind closed doors? Clearly I did not understand free market superiority, which this book was really about. Our good must triumph over their evil. Did I not see the obviously worst type of government in the world? The conversation clouded quickly with him reiterating confidence in market theory and me causing grief by asking if that survivor story was sound or complete on its own.

More recent news fortunately has brought a more balanced story than the material we discussed back then. It has become easier to discuss humanitarian crisis at a logical level since more data is available with more opportunity for analysis. Even so, the Associated Press points out that despite thousands of testimonials we still have an incomplete picture from North Korea and no hard estimates.

The main source of information about the prison camps and the conditions inside is the nearly 25,000 defectors living in South Korea, the majority of whom arrived over the last five years. Researchers admit their picture is incomplete at best, and there is reason for some caution when assessing defector accounts.

I noticed the core of the problem when watching Camp 14. This is a movie that uses first-person testimony from a camp survivor to give insights into conditions of North Korea. Testimony is presented as proof of one thing: the most awful death camps imaginable. Camp workers are also interviewed to back up the protagonist story. However a cautious observer would also notice the survivor’s view has notable gaps and questionable basis.

The survivor, who was born in the prison, says he became enraged with jealously when he discovered his mother helping his older brother. He turned in his own mother to camp authorities. That is horrible in and of itself but he goes on to say he thought he could negotiate better treatment for himself by undermining his family. Later he wonders in front of the camera whether as a young boy he might have mis-heard or mis-understood his mother; wonders if he sent his own mother to be executed in front of him without reason other than to improve his own situation.

The survivor also says one day much later he started talking to a prisoner who came from the outside, a place that sounded like a better world. The survivor plots an escape with this prisoner. The prisoner from the outside then is electrocuted upon touching the perimeter fence; the survivor climbs over the prisoner’s body, using it as insulation to free himself.

These are just a couple examples (role of his father is another, old man who rehabilitated him is another) that jumped out at me as informational in a different way than perhaps was intended. This is a survivor who describes manipulation for his own gain at the expense of others, while others in his story seem to be helping each other and working towards overall gains.

I’ve watched a lot of survivor story videos and met in person with prison camp survivors. Camp 14 did not in any way sound like trustworthy testimony. I gave it benefit of the doubt while wondering if we would hear stories of the others, those who were not just opportunists. My concern was this survivor comes across like a trickster who knows how to wiggle for self-benefit regardless of harm or disrespect to those around. Would we really treat this story as our best evidence?

The answer came when major elements of his stories appeared to have been formally disputed. He quickly said others were the ones making up their stories; he then stepped away from the light.

CNN has not been able to reach Shin, who noted in a Facebook post apologizing for the inaccuracies in his story that “these will be my final words and this will likely be my final post.”

My concern is that outsiders looking for evidence of evil in North Korea will wave hands over facts and try to claim exceptional circumstances. It may be exceptional yet without caution someone could quickly make false assumptions about the cause of suffering and act on false pretense, actually increasing the problem or causing worse outcomes. The complicated nature of the problem deserves more scrutiny than easy vilification based on stale reports from those in a position to gain the most.

One example of how this plays out was seen in a NYT story about North Korean soldiers attacking Chinese along border towns. A reporter suggested soldiers today are desperate for food because of a famine 20 years ago. The story simply did not add up as told. Everything in the story suggested to me the attackers wanted status items, such as cash and technology. Certain types of food also may carry status but the story did not really seem to be about food to relieve famine, to compensate for communist market failure.

Thinking back to Turing, how do we develop a logical framework let alone a universal one, to frame ethical issues around intervention against North Korea? Are we starting with the right assumptions as well as keeping an open mind on solutions?

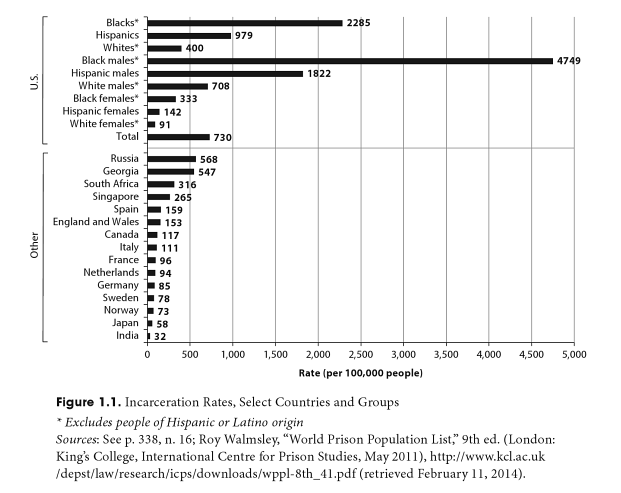

While we can dig for details to shame North Korea for its prison culture we also must consider the International Centre for Prison Studies ranks the United States second only to the Seychelles in per-capita incarceration rate (North Korea is not listed). According to 2012 data almost 1% of all US citizens are in prison. Americans should think about what prison quantitative analysis shows, such as here:

There also are awful qualitative accounts from inside the prisons, such as the sickening Miami testimony by a former worker about killing prisoners through torture, and prisoner convictions turning up to have zero integrity.

Human Rights Watch asked “How Different are US Prisons” given that federal judges have called them a “culture of sadistic and malicious violence”. Someone even wrote a post claiming half of the world’s worst prisons are in the US (again, North Korea is not listed).

And new studies tell us American county jails are run as debtor prisons; full of people guilty of very minor crimes yet kept behind bars by court-created debt.

Those issues are not lost to me as I read the UN Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Hundreds of pages give detailed documentation of widespread humanitarian suffering.

Maintaining a humanitarian approach, a universal theory of justice, seems like a good way to keep ourselves grounded as we wade into understanding crisis. To avoid the Turing disaster we must keep in mind where we are coming from as well as where we want others to go.

Take for example new evidence from a system where police arrest people for minor infractions and hold them in fear and against their will, in poor conditions without representation. I’ll let you guess where such a system exists right now:

They are kept in overcrowded cells; they are denied toothbrushes, toothpaste, and soap; they are subjected to the constant stench of excrement and refuse in their congested cells; they are surrounded by walls smeared with mucus and blood; they are kept in the same clothes for days and weeks without access to laundry or clean underwear; they step on top of other inmates, whose bodies cover nearly the entire uncleaned cell floor, in order to access a single shared toilet that the city does not clean; they develop untreated illnesses and infections in open wounds that spread to other inmates; they endure days and weeks without being allowed to use the moldy shower; their filthy bodies huddle in cold temperatures with a single thin blanket even as they beg guards for warm blankets; they are not given adequate hygiene products for menstruation; they are routinely denied vital medical care and prescription medication, even when their families beg to be allowed to bring medication to the jail; they are provided food so insufficient and lacking in nutrition that inmates lose significant amounts of weight; they suffer from dehydration out of fear of drinking foul-smelling water that comes from an apparatus on top of the toilet; and they must listen to the screams of other inmates languishing from unattended medical issues as they sit in their cells without access to books, legal materials, television, or natural light. Perhaps worst of all, they do not know when they will be allowed to leave.

And in case that example is too fresh, too recent with too little known, here is a well researched look at events sixty years ago:

…our research confirms that many victims of terror lynchings were murdered with out being accused of any crime; they were killed for minor social transgressions or for demanding basic rights and fair treatment.

[…]

…in all of the subject states, we observed that there is an astonishing absence of any effort to acknowledge, discuss, or address lynching. Many of the communities where lynchings took place have gone to great lengths to erect markers and monuments that memorialize the Civil War, the Confederacy, and historical events during which local power was violently reclaimed by white Southerners. These communities celebrate and honor the architects of racial subordination and political leaders known for their belief in white supremacy. There are very few monuments or memorials that address the history and legacy of lynching in particular or the struggle for racial equality more generally. Most communities do not actively or visibly recognize how their race relations were shaped by terror lynching.

[…]

That the death penalty’s roots are sunk deep in the legacy of lynching is evidenced by the fact that public executions to mollify the mob continued after the practice was legally banned.

The cultural relativity issues of our conflict with North Korea are something I really haven’t seen anyone talking about anywhere, although it seems like something that needs attention. Maybe I just am not in the right circles.

Perhaps I can put it in terms of a slightly less serious topic.

I often see people mocking North Korea for a lack of power and for living in the dark. Meanwhile I never see people connect lack of power to a June 1952 American bombing campaign that knocked out 90% of North Korea’s power infrastructure. This is not to say bomb attacks from sixty years ago and modern fears of dependency on infrastructure are directly related. It is far more complex.

However it stands to reason that a country in fear of infrastructure attacks will encourage resiliency and their culture shifts accordingly. A selfish dictator may also encourage resiliency to hoard power, greatly complicating analysis. Still I think Americans may over-estimate the future for past models of inefficiencies and dependency on centralized power. North Korea, or Cuba for that matter, could end up being global leaders as they figure out new decentralized and more sustainable infrastructure systems.

Sixty years ago the Las Vegas strip glare and consumption would be a marvel of technology, a show of great power. Today it seems more like an extravagant waste, an annoyance just preventing us from studying the far more beautiful night sky full of stars that need no power.

Does this future sound too Amish? Or are you one of the people ranking the night sky photos so highly that they reach most popular status on all the social sites? Here’s a typical 98.4% “pulse” photo on 500px:

Imagine what Google Glass enhanced for night-vision would be like as a new model. Imagine the things we would see if we reversed from street lights everywhere, shifting away from cables to power plants, and went towards a more generally sustainable/resilient goal of localized power and night vision. Imagine driving without the distraction of headlights at night, with an ability to see anyway, as military drivers around the world have been trained…

I’ll leave it at that for now. So there you have a few thoughts on humanitarian crisis, not entirely complete, spurred by a comment by Turing. As I said earlier, if you are working at Mandiant or Crowdstrike please think carefully about his story. Thanks for reading.