Anyone believe the claim by Steve Jobs in 2001 (see video below) that there was no personal computer in 1975?

Liar.

It is quite sad how someone can gleefully erase people to fraudulently highlight himself. Jobs was blatantly lying and it’s trivial to disprove him. The reporter really blew it by not challenging obviously false claims.

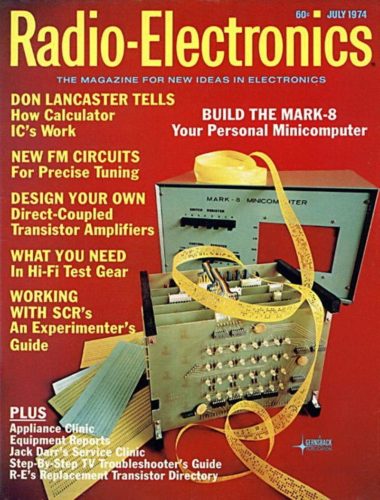

Being literate in history should require knowing that by 1974 personal computers already were on the cover of popular magazines.

It also is useful to know that the first personal computer (Xerox Alto from Palo Alto, where Woz worked and took many of his ideas to start Apple) had been operational in 1972 and introduced on 1 March 1973.

Note that in 1973 a personal computer already came with a high resolution bitmapped graphical display and a mouse.

What really seems to be obscured in that 2001 Steve Jobs interview — why 1975 matters so much as a particular turning point in time — is how Bill Mensch was able to create a layout completely by hand from the 6501 schematics and produce an inexpensive working CPU on his first try.

It begins at Motorola, where Chuck Peddle, Bill Mensch and several others were employed in the early 1970’s design the MC6800 processor and its peripherals. The 6800 was not a bad design, it was however, very expensive, a development board for it costing over $300. Chuck worked largely as the 6800 system architect, ensuring all the ICs worked well together and were what was needed to meet customers needs. He attended many calls to potential clients and noted that many were turned off by one thing, price. With that in mind he sought out to build a lower cost version of the 6800 using some of the newer processes available (specifically depletion mode NMOS vs the enhancement mode of the 6800). Motorola management wouldn’t hear it, they wanted nothing to do with a lower cost processor available to the masses. And with that, Chuck, Bill and over half the 6800 team left.

They ended up at MOS Technologies, which at the time was owned in large part by Allen/Bradley. It was there, at MOS under the direction of Chuck Peddle that the 6501/2 was borne.

It was THAT chip moment in 1975 that changed everything for the personal computer market (15% of the cost of an Intel 8080), which already existed.

In fact Apple arrived late by choosing the MOS 6502 after Commodore had done so already.

Who? Commodore. The company that in fact purchased MOS to save it and put in their own line of personal computers, although you’ll never hear Jobs mention either Commodore or MOS as personal computer innovators he was trying to copy.

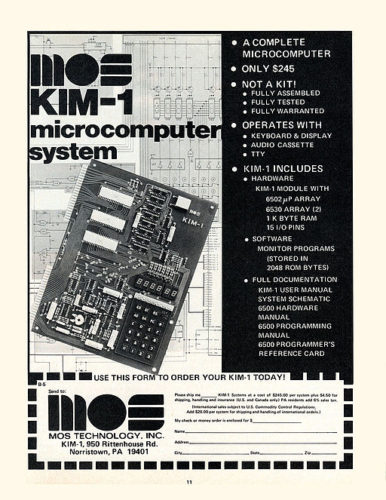

In 1975 Chuck Peddle designed the KIM-1 personal computer while at MOS, and he released it April 1976 as advertised by BYTE magazine. Again, popular widespread knowledge of a personal computer long before Apple came along to copy ideas.

Peddle also had developed a personal electronic transactor (PET) concept for a personal computer and in January 1977 displayed it at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Chicago.

Note this personal computer at the January CES trade show was months before Apple II (June 1977) or Radio Shack TRS80 (August 1977).

Steve Jobs in 2001 was quite literally erasing history by claiming there were no personal computers in 1975. First, the KIM-1 was designed by the same people who created the 6802 that Jobs was using. And second, CES had a personal computer on display from the same people who created the 6802 six months before both Apple and Radio Shack produced their competing products.

Jobs is saying “we had to create something where nothing existed” when he was doing the exact opposite: reacting to others creating things and promoting only himself unfairly as original.

Peddle had in fact had pitched his PET to Radio Shack hoping to have them retail it in stores (like Apple stores today). Radio Shack refused and it was soon afterwards, in the summer of 1977, that Commodore’s founder Jack Tramiel bought MOS Technologies — staff, patents, and production facilities.

And this is how the January 1977 PET personal computer moved into production. The Commodore acquisition (not to mention lawsuits from Motorola for the 6801, as well as a series of upgrades to memory, keyboard, and screens) led to delays of widespread availability until late in 1977.

Want to hear the real history? This is the real guy telling real truths right here:

(3h:48m:30s) The idea that Apple invented the personal computer, they literally were following us around. The Mac was a rip-off from [Xerox] Parc… With all due respect I don’t know what new things they’ve done. […] Everything was demonstrable in 1973. […] Star [in 1981, based on the 1972 Alto] was a great product it had all those things in it. Xerox deserves the credit.

(3h:51m:10s) Apple II by the way was getting its butt kicked by Radio Shack in the US and Europe, by us in Europe, until VisiCalc was on it. VisiCalc is what pulled them in… the first piece of software that was unique to the PC. Those guys at VisiCalc deserve the credit [for Apple’s success]. […]

I just want to be sure I give credit…

Peddle delivered a chip that made the inexpensive personal computer possible and then followed it by creating the worlds first “real” consumer-ready personal computer. And he even delivered the idea of the personal computer being sold in retail computer stores. Xerox had delivered the graphical screen and the mouse concepts years earlier on their Alto.

Apple definitely saved a lot of time by shamelessly taking other peoples’ ideas, as anyone can plainly see. The question remains whether Jobs intended to make more money by not crediting many of the people who had saved him so much time.