Would you buy a 1980 Datsun electric car?

Let me explain why such a car would exist in America, by telling you an obscure and old story that nobody really remembers anymore, and as far as I can tell has never been told in full before (given so many records/pieces are missing).

The New York Times in February 1981 boldly claimed the electric car was returning to America.

THE internal-combustion engine may have been king of the road for the last 70 years, but as a result of the gasoline hysteria that has struck the United States twice in the last decade, its chief competitor – the electric car – is again being seriously considered as an alternative.

Now here’s the big clue about where Datsun comes into play: GM and Gulf and Western are mentioned in the same sentence as “making commitments”.

“A whole new stage is being set for the electric car,” said John Makulowich, executive director of the Electric Vehicle Council, a trade association. “Major corporations like General Motors and Gulf and Western are making commitments to electric-vehicle engineering.” He attributed this in part to legislation giving financial aid and other incentives to research and development in this area.

Dozens of large and small companies are investing time and money in battery and electric-vehicle development, while hundreds, perhaps thousands, of individuals are tinkering in garages and laboratories to find an answer to America’s energy needs in a world of shrinking gasoline supplies. The answer, some think, could lie in the past.

Ah, well if the answer to electric cars lies in the past… will 1981 prove to be the answer for electric cars in 2021? Probably, but NYT wants us to go back even further in time since 1981 was current (pun not intended) for them back then.

By around 1910, one out of every three cars or trucks on American roads was there under electric power. But by 1920, Ford had sold nearly 10 million assembly-line-built gasoline-powered cars.

10 million gasoline-powered cars sounds like a lot of output until you look at the number of anti-Semitic hate propaganda and disinformation rags that Ford published.

I mean talk about “selling” a lot… Hitler even gave Ford a medal after taking millions of dollars to deliver products to American military, disappearing with it and instead showing up as ally of Nazi Germany!

I’m not kidding. That’s real, Ford’s abject failure to deliver as promised is even recorded in US Congressional debates.

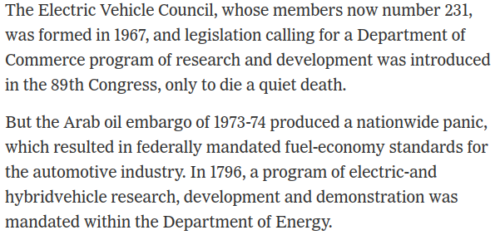

Anyway, setting all that dark and serious history aside, here’s my absolute favorite part of this NYT article. I have to screenshot it so you’ll believe me:

1796?! Wat.

Given the Department of Energy (DoE) was created in 1977 by President Carter (August 4 Department of Energy Organization Act abolishing the Federal Energy Administration and Energy Research and Development Administration) it seems very unlikely that the year 1796 is anything but a typo that still hasn’t been corrected.

I mean if America had electric vehicle commitments all the way back to 1796… hooo boy talk about this country being late to deliver on promises of freedom!

Speaking of promises, GM was literally saying in this 1981 article that they soon would be leading the world in electric cars. No, really they were saying how electric was going to be like a whopping 10 percent of their fleet 40 years into the future.

G.M. is planning to put a mass-produced electric car on the road by the mid-1980’s. Alex Mair, vice president in charge of technical staffs, said that by 2020, 10 to 15 percent of G.M.’s total production will be electric vehicles. “We think we’re leading the world this time around,” Mr. Mair said.

Someone could have stopped Mr. Mair right there and replied “10% is the opposite of leading the world, and a 40 year timeline is pathetic…just say never.”

Yeah, that didn’t turn out anything like what GM said. GM and electric car still are like saying oil and water.

But here is where the story gets really interesting, in two parts.

First, news of a breakthrough vehicle being developed by “Gulf and Western Industries” and second, calling out a Datsun employee driving an electric car around Los Angeles.

Earlier in 1980, Gulf and Western Industries announced a zincchloride battery system that David N. Judelson, the company’s president, called “a major achievement in the world of high technology – perhaps one of the most meaningful developments since the turn of the century.” The company said that vehicles powered with its battery had traveled 55 miles per hour for more than 150 miles on a single charge and that the battery system had a life cycle of more than 1,400 recharging cycles, or 200,000 miles.

[…]

Art Spinella, who works in public relations for Datsun in Los Angeles, has driven a converted Renault electric car since “the scare of ’73.” He said he just got tired of waiting in long gas lines. Powered by lead-acid batteries, the four-speed, late-60’s-model conversion cost just $600, and will run over 70 miles per hour and travel just over 60 miles before he has to recharge it. “People follow me off the expressway to ask what it is,” Mr. Spinella said, “They sometimes don’t believe what they just saw when I tell them it’s electric.” “Yes,” he added. “They work.”

Did the Datsun guy really plug a Renault (pun not intended)?

And now back to the point of this blog post, the 1980 Datsun electric car for sale.

A campaign called “Yes, they work” isn’t the best one I’ve ever seen. Yet such a definitive statement by Datsun PR in 1981 should have gotten a LOT more attention.

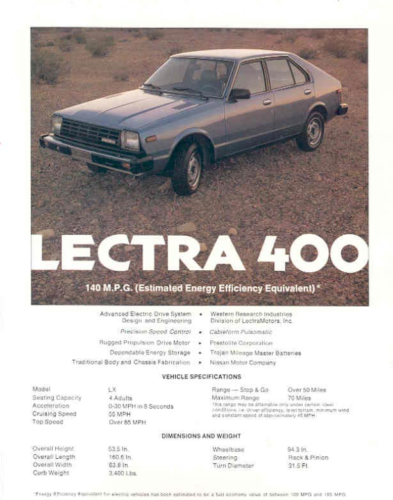

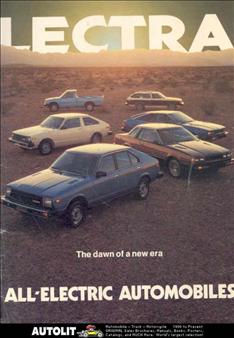

Apparently 1,200s Nissan vehicles without combustion engines were purchased by the US government under the 1970 Clear Air Act (with the 1976 Electric and Hybrid Vehicle Research, Development, and Demonstration Act) to make electric cars for power companies and municipality workers; eventually these vehicles ended up in the hands of “Lectra Motors” of Las Vegas.

Let me just stop here to point out right now that the Department of Energy official history of this period is provably false and misleading.

…vehicles developed and produced in the 1970s still suffered from drawbacks compared to gasoline-powered cars. Electric vehicles during this time had limited performance — usually topping at speeds of 45 miles per hour — and their typical range was limited to 40 miles before needing to be recharged.

That is just not true. “Typical range” and “usually topping” are weasel words because they’re talking averages, hiding the fact that cutting-edge advances of that day proved far, far better performance.

Here’s a late 1970s Lectra 400 brochure blowing away those deflated numbers (top speed over 65 mph, and 70 mile range, both far more than necessary in urban environments).

Let me explain with some more history.

The relationship between all these parties in the late 1970s might sound strange to the modern ear until you roll way back to the end of WWII and consider one of Nissan’s first products under occupation by Allied forces was an electric car.

In 1947, the company succeeded in creating a prototype 2-seater truck (500-kg load capacity) with a 4.5-horsepower motor and a new body design. It was named “Tama” after the area where the company was based. Its top speed was 34 km/h (21 mph). Next, the company created its first passenger car. With two doors and seating for four, it boasted a top speed of 35 km/h (22 mph) and a cruising range of 65 km (40 miles) on a single charge.

In other words, what the Department of Energy was claiming to be 1970s limitations were really from the 1940s! By the 1970s the new electric cars were capable of 70 mph and 70 mile range, far exceeding electric car requirements of that time.

To put it another way, context matters. Tokyo in 1945 had been burned to the ground (over 50% destroyed by months of firebomb raids) and industrial production let alone gasoline was non-existent.

Engineers from a Japanese Aircraft company in Tokyo were hired into Nissan and set about designing an electric car that would restart their country’s infrastructure and commerce.

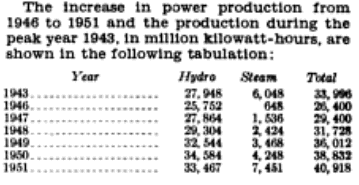

They immediately put into production a car that could run off hydro-electricity from the mountains outside devastated Tokyo. Electricity infrastructure repairs meant production jumped nearly 55% right after war ended and here you can see hydro’s stability:

Even manufacturing of the car itself was supposedly designed to run on excess electricity in the immediate after-war years. Sure, the car was limited, but it was aircraft engineers redeployed to civilian needs and delivering something where there had been nothing.

There are a lot of “airplane-engineers must have built this” innovation moments when looking at a Tama, especially when you see a battery refuel concept of Nissan in 1947 giving drivers a fast swap on both sides like reloading wings for bombing runs:

Military engineers designing electric cars after WWII…hold that thought.

Now back to all the fancy sounding language from GM about leading the world in electric vehicles. Remember that? Instead GM used its giant budget to buy a majority stake of small but very plausible emerging electric car companies in Las Vegas to shut them down completely, allegedly even destroying records (if you know of any Lectra files, please let me know).

Any guesses why the Nissan electric car development with the US evaporated in 1981? Ronald Reagan.

It doesn’t get mentioned much, but in 1981 the Reagan Administration asked Japanese automakers to impose a “voluntary export restraint” (VER), which capped at 1.68 million the number of cars Japan could send to the United States each year. Reportedly, this was under threat of an outright tariff, but the VER accomplished just about the same thing.

Thus GM and Reagan ruined an early emerging success story involving Nissan and US government from 1979-1981 — thousands of cars were very briefly released for Gulf and Western (WRI), which were transitioned into LectraMotors run by Albert Joseph Sawyer (per his obituary from 2012).

Thus GM and Reagan ruined an early emerging success story involving Nissan and US government from 1979-1981 — thousands of cars were very briefly released for Gulf and Western (WRI), which were transitioned into LectraMotors run by Albert Joseph Sawyer (per his obituary from 2012).

After moving to Las Vegas in 1960, [the Navy veteran] worked for [Edgerton, Germeshausen, and Grier defense contractor] as an electrical engineer. In 1974, he made his first electric car. After retiring from EG&G in 1978, he formed LectraMotors to mass produce electric cars. He was a true visionary and pioneer in the electric car industry. Some cars are on the road to this very day.

Here’s how a US government report put it in 1979, with only a brief mention of testing the Lektrikar II, which at that time was still WRI:

And here’s a promotional video for the “advanced Zinc Chloride energy storage system” that boasted of $27 million in US government funding:

Did I say military engineers designing electric cars after WWII? Responding to a Japanese energy crisis in 1946 had quite a lot in common with responding to an American energy crisis in 1976, although I don’t see anyone make the obvious connection here from Nissan’s aeronautical engineers to EG&G’s…

EG&G jobs near Las Vegas meant something rather special. I didn’t find Albert Sawyer’s name on a 1967 drawing from EG&G “Special Projects” team, yet the imagery depicts a certain sentiment about the world for top engineering teams when the CIA terminated their Operation OXCART (SR-71 Blackbird).

Think about the Japanese engineers who built planes, shifting after defeat in WWII to making electric cars, giving those to engineers in America who were shifting from a company making the SR-71 to a new company to mass produce and represent cutting-edge electric cars.

Instead of “Yes, it works” perhaps the PR guy from Datsun could have said something like “If engineers working on our new 310 model can build a real-life R2-D2 astral navigation system for a top-secret long-range, high-altitude, Mach 3+ strategic reconnaissance aircraft, just wait until you see what they can do for the electric car”.

And so we come to the conclusion of this post.

One of these rarest of rare American cars sold by an ex-EG&G engineer’s company Lectra still exists today in Santa Cruz, California because… of course.

The car originally was badged as Datsun (US brand-name for Nissan) 310 Lektrikar II.

Nobody knows how many existed. Again, it is believed GM intentionally destroyed records during the Reagan Administration to cheat history of these emerging electric car projects.

This Lektrikar II has been “modified” over the years but fundamentally it’s always been a fine vehicle by even today’s standards.

Weirdly you will find no mention of any of this real history on Wikipedia’s retelling of electric car history, let alone any other “authoritative” versions of electric car company history in America. It’s almost impossible to find any mention of one at all anywhere.

The surviving Lektrikar II started with eighteen 6V golf-cart batteries (US Battery US-145 Lead-Acid Flooded with 7 front, 11 rear), and replaced them with a simpler array of nine 82-pound Trojan 1275MV automobile 12V Lead-Acid Flooded with 4 front, 5 rear.

The motor is a Prestolite 7.2 inch Series Wound DC 22 HP, with a 4-speed drivetrain and clutch.

And the controller is said to be a Curtis 1221C MOSFET transistor Technology, 15,000 cycles per second, 400 Amps.

It’s for sale… but really the story is that in 1981 the Datsun PR guy was telling people that converting his daily driver car to electric (for 60 mile range capable of 70 mph) cost around $600 and GM was telling the world they would be the leaders in this market while working behind the scene to shut it all down.

More photos: