This (draft) post basically comes after reading one called “The Feds Got the Sony Hack Right, But the Way They’re Framing It Is Dangerous” by Robert Lee. Lee stated:

At its core, the debate comes down to this: Should we trust the government and its evidence or not? But I believe there is another view that has not been widely represented. Those who trust the government, but disagree with the precedent being set.

Lee is not the only person in government referring to this core for the debate. It smacks of being forced by those in government to choose one side or the other, for or against them. Such a binary depiction of governance, such a call for obedience, is highly politically charged. Do not accept it.

I will offer two concepts to help with the issue of choosing a path.

- Trust but Verify (As Gorbachev Used to Tell Reagan)

- Agile and Social/Pair Development Methods

So here is a classic problem: non-existent threats get over inflated because of secret forums and debates. Bogus reports and false pretense could very well be accidents, to be quickly corrected, or they may be intentionally used to justify policies and budgets requiring more concerted protest.

If you know the spectrum are you actually helping improve trust in government overall by working with them to eliminate error or correct bias? How does trusting government and its evidence while also wanting to also improve government fit into the sides Lee quotes? It seems far more complicated than writing off skeptics as distrustful of government. It also has been proven that skeptics help preserve trust in government.

Take a moment to look back at a false attribution blow-up of 2011:

Mimlitz says last June, he and his family were on vacation in Russia when someone from Curran Gardner called his cell phone seeking advice on a matter and asked Mimlitz to remotely examine some data-history charts stored on the SCADA computer.

Mimlitz, who didn’t mention to Curran Gardner that he was on vacation in Russia, used his credentials to remotely log in to the system and check the data. He also logged in during a layover in Germany, using his mobile phone. …five months later, when a water pump failed, that Russian IP address became the lead character in a 21st-century version of a Red Scare movie.

Everything deflated after the report was investigated due to public attention. Given the political finger-pointing that came out afterwards it is doubtful that incident could have received appropriate attention in secret meetings. In fact, much of the reform of agencies and how they handle investigations comes as a result of public criticism of results.

Are external skepticism and interest/pressure the key to improving trust in government? Will we achieve more accurate analysis through more parallel and open computations? The “Big Data” community says yes. More broadly speaking so many have emulated the Aktenzeichen XY … ungelöst “help police solve crimes” TV show since it started in 1967, a general population also probably would agree.

Trust but Verify

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher famously once quipped “Standing in the middle of the road is very dangerous; you get knocked down by the traffic from both sides.” Some might take this to mean it is smarter to go with the flow. As Lee highlighted, they say pick a side either for trust in government or against. Actually, it often turns out to be smarter to reject this analogy.

Imagine flying a plane. Which “side” do you fly on when you see other planes flying in no particular direction? Thatcher was renowned for false choice risk-management, a road with only two directions where everyone chooses sides without exceptions. She was adamantly opposed to Gorbachev tearing down the wall, for example, because it did not fit her over-simplified risk management theory. Verification of safety is so primitive in her analogy as to be worthless to real-world management.

Asking for verification should be a celebration of government and trust. We trust our government so much, we do not fear to question its authority. Auditors, for example, look for errors or inconsistencies in companies without being seen as a threat to trust in those companies. Executives further strengthen trust through skepticism and inquiry.

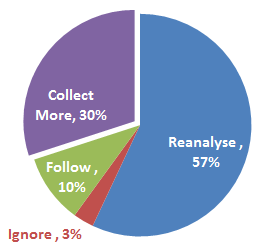

Consider for a moment an APT (really, no pun intended) study called “Decisive action: How businesses make decisions and how they could do it better“. It asked “when taking a decision, if the available data contradicted your gut feeling, what would you do?”

Releasing incomplete data could be reasonably expected to have 90% push back for more data or more analysis, according to this study. Those listening to the FBI claim North Korea is responsible probably have a gut feeling contradicting the data. That gut feeling is more “are we supposed to accept incomplete data as proof of something, because been there done that, let’s keep going” than it is “we do not trust you”.

In the same study 38% said decisions are better when more people are involved, and 38% said more people did not help, so quantity alone isn’t the route to better outcomes. Quality remains a factor, so there has to be a reasonable bar to input, as we have found in Big Data environments. The remaining 25% in the survey could tip the scale on this point, yet they said they were still collecting and reanalyzing data.

My argument here is you can trust and you still can verify. In fact, you should verify where you want to maintain or enhance trust in leadership. Experts definitely should not be blandly labelled as anti-government (the 3% who ignore) when they ask for more data or do reanalysis (the 90% who want to improve decision-making).

Perhaps Mitch Hedberg put it best:

I bought a doughnut and they gave me a receipt for the doughnut. I don’t need a receipt for a doughnut. I just give you the money, you give me the doughnut. End of transaction. We don’t need to bring ink and paper into this. I just can not imagine a scenario where I had to prove I bought a doughnut. Some skeptical friend. Don’t even act like I didn’t get that doughnut. I got the documentation right here. Oh, wait it’s back home in the file. Under D.

We have many doughnut scenarios with government. Decisions are easy. Pick a doughnut, eat it. At least 10% of the time we may even eat a doughnut when our gut instinct says do not because impact seems manageable. The Sony cyberattack however is complicated with potentially huge/unkown impact and where people SHOULD imagine a scenario requiring proof. It’s more likely in the 90% range where an expert simply going along with it would be exhibiting poor leadership skills.

So debate actually boils down to this: should the governed be able to call for accountability from their government without being accused of complete lack of trust? Or perhaps more broadly should the governed have the means to immediately help improve accuracy and accountability of their government, provide additional resources and skills to make their government more effective?

Agile and Social/Pair Development Methods

In the commercial world we have seen a massive shift in IT management from waterfall and staged progress (e.g. environments with rigorously separated development, test, ready, release, production) to developers frequently running operations. Security in operations has had to keep up and in some cases lead the evolution.

Given the context above, where embracing feedback-loops leads to better outcomes, isn’t government also facing the same evolutionary path? The answer seems obvious. Yes, of course government should be inviting criticism and be prepared to adapt and answer, moving development closer to operations. Criticisms could even be more manageable by nature of a process where they occur more frequently in response to smaller updates.

Back to Lee’s post, however, he suggests an incremental or shared analysis would be a path to disaster.

The government knew when it released technical evidence surrounding the attack that what it was presenting was not enough. The evidence presented so far has been lackluster at best, and by its own admission, there was additional information used to arrive at the conclusion that North Korea was responsible, that it decided to withhold. Indeed, the NSA has now acknowledged helping the FBI with its investigation, though it still unclear what exactly the nature of that help was.

But in presenting inconclusive evidence to the public to justify the attribution, the government opened the door to cross-analysis that would obviously not reach the same conclusion it had reached. It was likely done with good intention, but came off to the security community as incompetence, with a bit of pandering.

[…]

Being open with evidence does have serious consequences. But being entirely closed with evidence is a problem, too. The worst path is the middle ground though.

Lee shows us a choice based on false pretense of two sides and a middle full of risk. Put this in context of IT. Take responsibility for all the flaws and you delay code forever. Give away all responsibility for flaws and your customers go somewhere else. So you choose a reasonable release schedule that has removed major flaws while inviting feedback to iterate and improve before next release. We see software continuously shifting towards the more agile model, away from internal secret waterfalls.

Lee gives his ultimate example of danger.

This opens up scary possibilities. If Iran had reacted the same way when it’s nuclear facility was hit with the Stuxnet malware we likely would have all critiqued it. The global community would have not accepted “we did analysis but it’s classified so now we’re going to employ countermeasures” as an answer. If the attribution was wrong and there was an actual countermeasure or response to the attack then the lack of public analysis could have led to incorrect and drastic consequences. But with the precedent now set—what happens next time? In a hypothetical scenario, China, Russia, or Iran would be justified to claim that an attack against their private industry was the work of a nation-state, say that the evidence is classified, and then employ legal countermeasures. This could be used inappropriately for political posturing and goals.

Frankly this sounds NOT scary to me. It sounds par for the course in international relations. The 1953 US decision to destroy Iran’s government at the behest of UK oil investors was the scary and ill-conceived reality, as I explained in my Stuxnet talk.

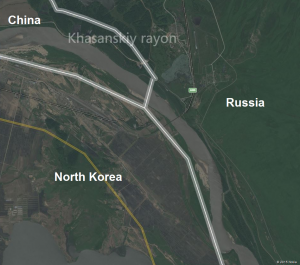

One thing I repeatedly see Americans fail to realize is that the world looks in at America playing a position of strength unlike others, jumping into “incorrect and drastic consequences”. Internationally the one believed most likely to leap without support tends to be the one who perceives they have the most power, using an internal compass instead of true north.

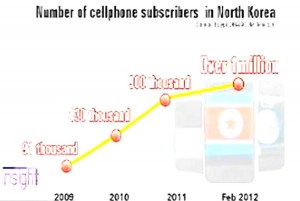

What really is happening is those in American government, especially those in the intelligence and military communities, are trying to make sense of how to achieve a position of power for cyber conflict. Intelligence agencies seek to accumulate the most information, while those in the military contemplate definitions of winning. The two are not necessarily in alignment since some definitions of winning can have a negative impact on the ability to gather information. And so a power struggle is unfolding with test scenarios indispensable to those wanting to establish precedent and indicators.

This is why moving towards a more agile model, away from internal secret waterfalls, is a smart path. The government should be opening up to feedback, engaging the public and skeptics to find definitions in unfamiliar space. Collecting and analyzing data are becoming essential skills in IT because they are the future of navigating a world without easy Thatcher-ish “sides” defined. Lee concludes with the opposite view, which again presents binary options.

The government in the future needs to pick one path and stick to it. It either needs to realize that attribution in a case like this is important enough to risk disclosing sources and methods or it needs to realize that the sources and methods are more important and withhold attribution entirely or present it without any evidence. Trying to do both results in losses all around.

Or trying to do both could help drive a government out of the dark ages of decision-making tools. Remember the inability of a certain French General to listen to the skeptics all around him saying German invasion through the forest was imminent? Remember how that same General refused to use radio for regular updates, sticking to a plan, unlike his adversaries on their way to overtake his territory with quickly shifting paths and dynamic plans?

Bureaucracy and inefficiency leads to strange overconfidence and comfort in “sides” rather than opening up to unfamiliar agile and adaptive thinking. We should not confuse the convenience in getting everyone pointed in the same direction with true preparation and skills to avoid unnecessary losses.

The government should evolve away from tendencies to force complex scenarios into false binary choices, especially where social and pairing methods makes analysis easily improved. In the future, the best leaders will evaluate the most paths and use reliable methods to gradually reevaluate and adjust based on enhanced feedback. They will not “pick one path and stick to it” because situational awareness is more powerful and can even be more consistent with values (maintaining moral high-ground by correcting errors rather than doubling-down).

I’ve managed to avoid making any reference to football. Yet at the end of the day isn’t this all really about an American ideal of industrialization? Run a play. Evaluate. Run another play. Evaluate. America is entering a world of cyber more like soccer (the real football) that is far more fluid and dynamic. Baseball has the same problem. Even basketball has shades of industrialization with machine-like plays. A highly-structured top-down competitive system that America was built upon and that it has used for conflict dominance is facing a new game with new rules that requires more adaptability; intelligence unlocked from set paths.

Update 24 Jan: Added more original text of first quote for better context per comment by Robert Lee below.