Background and History

On November 24, 2014, employees at Sony Pictures Entertainment arrived at work to find their computer screens displaying a red skeleton and threats from a group calling itself “Guardians of Peace.” Within hours, the company’s network was gutted. Unreleased films, executive emails, salary data, and social security numbers for 47,000 current and former employees were exfiltrated and systematically dumped online. The attack coincided with Sony’s planned release of “The Interview,” a comedy depicting the assassination of Kim Jong-un.

By December, the FBI had attributed the attack to North Korea. This attribution was met with immediate skepticism from portions of the security community, not because defending the DPRK seemed appealing, but because the technical evidence presented publicly was thin and the geopolitical convenience was obvious. The debate quickly polarized into camps: those accepting the government’s word and those demanding proof.

Disaster Recovery

What makes the Sony breach remarkable isn’t the exfiltration, since that’s so common, but the angle of destruction. The attackers deployed wiper malware that rendered systems unbootable, forcing Sony to revert to fax machines, pencil and paper checks for weeks. This went beyond espionage into punishment as proof. The operational tempo suggested planning and resources far beyond disgruntled insiders, the theory floated by some skeptics. The sophistication of destruction was good enough, we were left with little to say about who held the match.

Material Impact

Sony’s losses extended beyond the $35 million in immediate IT remediation. The company pulled a film “The Interview” from theatrical release after theater chains received threats, then reversed course under public pressure. Executives resigned. Lawsuits mounted. The strategic value of the attack demonstrating that a major American corporation could be brought to its knees, and made to self-censor, far exceeded whatever intelligence value the stolen emails provided. Someone invested significant resources for a demonstration of power.

Sophisticated Attack

Here’s where the attribution debate gets most interesting. Critics of the FBI’s conclusion often argue that North Korea is too isolated and therefore lacks technical capability for such an operation. The DPRK is portrayed as a hermit kingdom where citizens have no internet access and technology stopped advancing in 1953.

This framing is wrong, and lazy.

First, North Korea worked to a stalemate in war by effectively disappearing. They know appearing incompetent or not at all, forcing capabilities underground, is a tactical advantage. Second, it confuses the known poverty of North Korean citizens with the unknown capabilities of its military and intelligence services. States that leak failures to feed their populations can still build cyber weapons let alone nukes; states with limited civilian internet can still run offensive operations. The question isn’t whether every North Korean has broadband access. The question is whether intelligence services have the infrastructure and connectivity anywhere anytime to project power through networks.

US Military Industrial Congressional Complex

The rush to attribute and the subsequent calls for retaliation fit a familiar pattern. Cyber Pearl Harbor rhetoric has been building for years, and the defense establishment always seems to need demonstrable threats to justify budgets. Motivated reasoning cuts both directions, and skepticism of government claims can be just as reflexive as acceptance. We should examine the actual evidence rather than accepting appeals to classified sources. When Director Clapper tells us the evidence is compelling but we can’t see it, we’re being asked to trust institutions with documented records of deception on matters of war and peace.

Cold/Proxy Wars

The Sony hack exists within a longer history. The Korean War never formally ended. The DPRK has been under American sanctions for decades. Both nations have reasons to view the other as an adversary, and both have conducted operations against each other. North Korean defectors report that cyber operations are a priority investment precisely because they offer asymmetric advantages against a conventionally superior adversary. None of this proves attribution in a specific case, but it establishes that North Korea has motive, has stated intent, and has been building capability. The question becomes: what capability, exactly?

Attribution: DPRK Use of Technology

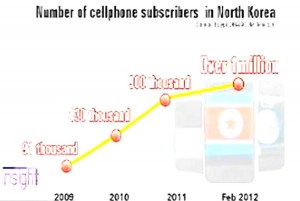

Apparently there are over 2 million 3G users in Pyongyang, as the Google CEO mentioned on Google+

North Korean limits right now.

There is a 3G network that is a joint venture with an Egyptian company called Orascom. It is a 2100 Megahertz SMS-based technology network, that does not, for example, allow users to have a data connection and use smart phones. It would be very easy for them to turn the Internet on for this 3G network. Estimates are that are about a million and a half phones in the DPRK with some growth planned in the near future.

There is a supervised Internet and a Korean Intranet. (It appeared supervised in that people were not able to use the internet without someone else watching them). There’s a private intranet that is linked with their universities. Again, it would be easy to connect these networks to the global Internet.

Schmidt’s observations from his 2013 visit are useful but incomplete. He describes what ordinary North Koreans can access, not what the state’s offensive capabilities look like. A country can maintain a locked-down domestic internet while running sophisticated external operations—in fact, that’s precisely the configuration you’d expect from a surveillance state that also wants to project cyber power.

North Korean links to the Internet

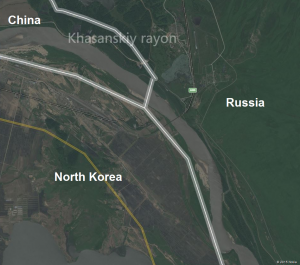

In May 2006 TransTeleCom Company and North Korea’s Ministry of Communications signed an agreement for the construction and joint operation of a fiber-optic transmission line in the section of the Khasan–Tumangang railway checkpoint. This connects North Korea through a fiber optic cable with Vladivostok, crossing the Russia-North Korea border at Tumangang.

I also read a while ago that the Egyptian company Orascom had setup North Korea’s Koryolink. Then I noticed Russians were taking a massive interest in Orascom. This looked a little over-hyped yet business is business and there was a good chance a real network was being developed for general public use. Orascom was kind enough to release marketing material that provided a (simulated) map using the Huawei OptiX iManager

Everyone knows that mobile phones are the future of Internet use, especially in emerging markets. Although I have read about extensive sneakernet access (smuggled storage devices plugged into laptops in remote cabins) that obviously doesn’t scale. Instead the Orascom network is supposedly leading to a boom in cellphone adoption.

My thought after reading the Orascom connection is that they’re probably going to link up to Russian telecom. Russians moving in on Orascom suggests they would continue investing more broadly, connecting to back-haul and other trade routes. A quick check of flights, to my surprise, showed indeed there were trips regularly going north into Russia. Although I expect to see flights to China, instead I found a very good indication that there were legs to the Russian investment direction a few years ago.

Flights definitely reveal important and current trade links. But we still need to be on the ground to establish knowledge about topology and routes for cables.

A quick and easy answer was to look at telecom companies bragging about their upgrades. For example, here’s a 2011 Press Release called “LEADING RUSSIAN SERVICE PROVIDER FUTURE-PROOFS HIGH-PERFORMANCE INFRASTRUCTURE WITH JUNIPER NETWORKS“.

TTK (TransTeleCom), a major communication provider in Russia that operates one of the country’s largest fiber networks, has chosen Juniper Networks MX Series 3D Universal Edge Routers to provide the Ethernet bandwidth required to ensure high-speed connectivity while delivering innovative applications and services such as IP-VPN, L2-VPN, video conference across Russia and IP-transit to its subscribers across 75,000 km of cables running along railway lines and 1,000 access nodes

Sounds like Juniper could be running the backbone we’re going to be looking into for North Korean traffic, no? Notice below a red line all the way to the right that takes a straight north-south run towards North Korea. If you squint you can even see a giant grey arrow indicating service going directly to…yup, North Korea.

This is just a PR map, however. Let’s back it up a little. That 75,000km of fiber connecting 1,000 nodes in trans-asia follows the established trade paths cut by rail, of course. Trains tend to do a marvelous job of providing insights for data (much less expensive to reuse existing paths and access is obvious). One might even argue trains are more appropriate than planes to show trends in the DPRK, given how much the leaders have said they prefer trains.

Other than using obvious and easy PR, or following rail, a fun next step might have been to poke around shipping and undersea cables. There seemed no reason to believe a cable would go undersea (except maybe further north to Japan or following the oil pipeline project that Japan funded in Nakhodka). After following pipelines and undersea routes to Russian borders (basically none of interest) I put that idea on the side-burner and looked more closely again at the railroads to border areas.

My eye ended up getting caught on the railroad crossing just southeast of a finger of Chinese territory, about 20km upstream of entry into the Sea of Japan. At Tumangan sits a railroad bridge connecting North Korea to Russia across a river. On several different maps I found Russia extends over the river to the south bank, perhaps cementing against any claims of China extending further to the Sea. Nokia’s map makes it most clear.

The proximity of countries seems to be settled by the Beijing Agreement of 1860. Perusing eye-level photographs uncovered this explanation due to Russian and Chinese border posts sitting literally right next to each other without any divider.

Russia pillar by hanjiang.dudiao

Speaking of observations at eye-level, the river has very low banks that probably move (just the north four spans are over water, out of eight total, potentially explaining a border being so far south). Satellite images show crops in the fields ruined by flooding. It also is clear the bridge is for trains, while wires are not seen. The bridge seems to be quite the serious construction for such a rural area. It’s not magnificent yet it suggests ability to handle heavy/industrial loads.

Khasansky District, Primorsky Krai, Russia by EdwMac

All very interesting points about this area but let’s get back to train routes. I dig a little for routes running southbound towards North Korea from Russia. Ask me sometime about how I almost accidentally ended up in Ukraine while traveling on a midnight train through Hungary. Anyway there are two trains a day from Khabarovsk, Khabarovsk Krai (four trains a day northbound) crossing 800km in about 12 hours.

Fortuitously I also find a ticket from a passenger traveling from Russia to Pyongyang via Tumangan, crossing from a Russian station in a border town called Khasan.

Train ticket “Pyongyang via Tumangan” by Helmut

Here’s the train just before it crosses from Khasan into Tumangan. Very nice picture.

Train in Khasan, Primorsky Krai, Russia just across the border from North Korea by mwbild

I poke around the Khasan train ride details, looking for cables and lines headed southbound. The Russian end of the bridge doesn’t look promising. There is a lot going on in this photo but not enough to say cables are running through.

So I keep poking and take a look from the other end. The North Korean end of the bridge tells a different story.

Bingo. See the left side? Cables on a pole extending to supports on the bridge, running into Russia. I would love to go on yet it feels like we’re at a point where we have achieved what we set out to accomplish: clear evidence North Korea has infrastructure along trade routes connecting directly to Russia.

A Bridge to Somewhere

So where does this leave us on attribution? I have not yet proven North Korea hacked Sony. What I’ve demonstrated is that the “North Korea couldn’t possibly have the infrastructure” argument doesn’t survive contact with publicly available evidence.

The DPRK has fiber optic connectivity to Russia through TransTeleCom, running along established rail corridors, crossing at the same Khasan-Tumangang bridge that’s been moving trains and trade for decades. The 2006 agreement between TTK and North Korea’s Ministry of Communications predates the Sony hack by eight years. This isn’t speculative future capability because it’s installed infrastructure.

The hermit kingdom narrative serves multiple interests. It lets skeptics dismiss attribution without examining evidence. It lets the US government claim unique insight that only classified sources can provide. And it lets everyone avoid the harder question: if North Korea does have offensive cyber capability enabled by Russian and Chinese infrastructure, what does that mean for how we think about state-sponsored attacks, sanctions regimes, and the geography of the internet?

Cables follow rail lines because that’s where the rights-of-way are. They cross borders where bridges already exist. The internet is real copper and glass running through physical territory controlled by states with their own interests. North Korea’s connectivity runs through Russia and China because that’s who shares borders and has reasons to maintain the connection. Understanding that topology matters more than arguing about whether we have receipts for Kim Jong-un personally approving anything like a hack.

I don’t know yet who hit Sony. But I know who could have, and I know the infrastructure to do it runs across a bridge I can show you on a map.