For forty years, gamers have treated Bowser’s name origin as if an unsolved mystery.

The official line from Nintendo is that it’s “unconfirmed.” Wikipedia likes to rest on “multiple competing theories.” The gaming press periodically revisits the question, shrugs, and moves on.

They’ve all been looking in the wrong direction.

Instead, in plain sight, the name has been confirmed not by Nintendo but by the people who actively avoided the name.

Hating on Korea

Mario’s nemesis in Japanese has always been called Kuppa, named by Shigeru Miyamoto after gukbap, a Korean rice soup dish. Miyamoto reportedly also considered naming him after yukhoe (raw beef) and bibimbap. The man liked references to Korean food as villainous.

When Super Mario Bros. was localized for the American market in 1985, someone at Nintendo of America decided that slights directed at Korea like “Kuppa” wouldn’t work for Americans. They needed another name for a villain, the fire-breathing turtle-dragon.

They chose “Bowser.”

Apparently, nobody wrote down why. Nobody filed a memo we can cite. The decision was made by a small team. Nintendo of America had roughly 35 employees at the time, no formal localization department, and was operating out of Redmond, Washington while frantically trying to launch the NES into a market still traumatized by the 1983 video game crash.

The Obvious Pop Villain

In 1985, if you were an American in your twenties working in entertainment-adjacent industries, there was a very specific cultural reference sitting in your mental inventory for “tough guy with a funny name.”

Bowzer.

Jon “Bowzer” Bauman was the breakout star of Sha Na Na, the nostalgia doo-wop group that had been inescapable in American pop culture:

- Woodstock, 1969 (immortalized in the documentary)

- The movie Grease, 1978 (massive hit)

- The Sha Na Na TV variety show, 1977-1981 (syndicated for years after)

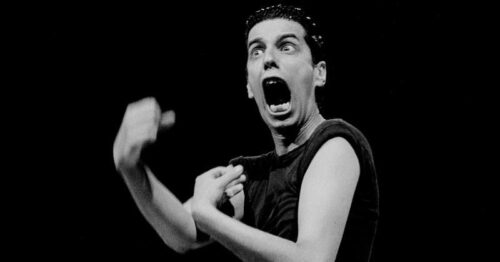

Bowzer’s whole act was a villain persona with the muscle shirt, the slicked-back hair, the theatrical sneer. The comedy he created was in the contrast: an intimidating figure performing sincere 1950s love ballads. The tough guy who sings love songs. The cruel kindness jokes, like saying he was told by his manager he’s not very nice, so he’s trying to prove him wrong by asking everyone to send get well cards to his hospital room.

The spelling difference is notable. Localization teams routinely adjust spellings to avoid trademark issues or to make names feel more “natural” in the target language. Bowzer becomes Bowser.

The Negative Proof

Here’s where it gets interesting.

In 1993, Hollywood produced the infamous live-action Super Mario Bros. movie. Dennis Hopper played the villain. But in the film, he’s called “President Koopa” and never Bowser.

Why?

In an interview, screenwriter Parker Bennett explained the decision. They didn’t use “Bowser” because, and this is the key clue, it immediately brought to mind “the ’50s Sha Na Na guy.”

Boom.

This wasn’t research. This wasn’t something they had to look up. The association was reflexive. Instant. Obvious.

The filmmakers in 1993 knew exactly where the name came from. It was so obvious to them that they actively avoided it, worried the comedic association would undermine their (inexplicably serious) film.

Bowser no longer was cool, no longer was pop. A generation had passed.

If it was obvious to Hollywood screenwriters in 1993, it was obvious to Nintendo of America in 1985. The difference is that in 1985, someone saw the connection as a feature rather than a bug. A tough villain name with existing cultural resonance? Perfect. Ship it.

The Dismissal

I see some historians dismissed the Sha Na Na theory partly because “the trend of naming Mario characters after musicians hadn’t started yet.” This is terrible reasoning.

Conventions don’t emerge from nowhere. They start with individual decisions that later become patterns.

We know exactly how Nintendo of America’s localization worked in this era because we have documented cases from just a few years later. When Super Mario Bros. 3 was localized in 1990, a product analyst named Dayvv Brooks was tasked with naming Bowser’s seven children, the Koopalings.

Brooks, a former Tower Records employee and DJ, immediately reached for musicians:

- Ludwig von Koopa (Beethoven)

- Roy Koopa (Roy Orbison)

- Wendy O. Koopa (Wendy O. Williams)

- Iggy Koopa (Iggy Pop)

- Lemmy Koopa (Lemmy Kilmister)

- Morton Koopa Jr. (Morton Downey Jr.)

We only know this because someone tracked Brooks down in 2015 and asked him. He didn’t file a memo in 1990. There was no documentation. The knowledge existed only in his memory until a journalist finally thought to ask the right question.

Brooks wasn’t at Nintendo in 1985. But the method he used of reaching for pop culture references that “just fit”, clearly was part of how NoA approached localization. The Koopalings weren’t an innovation. They were a continuation.

Who Are You Going to Call?

The leading candidate is Howard Phillips.

Phillips was NoA’s fifth employee, starting in 1981 as a warehouse manager. By 1985, he had evolved into the company’s key liaison between Japanese developers and the American market. His job was explicitly to advise on what would resonate with US audiences — including, according to documented sources, advising on “the renaming of characters.”

Phillips was born in 1958. In 1985, he was 27 years old — exactly the demographic for whom Sha Na Na’s Bowzer would have been a vivid cultural reference. He was also, by all accounts, deeply immersed in pop culture and an avid consumer of entertainment media.

Has anyone ever directly asked Howard Phillips: “Did you name Bowser? Were you thinking of Sha Na Na?”

Phillips is still active. He does interviews about Nintendo history. He’s been asked about the NES launch, about Nintendo Power, about his role in rejecting the Japanese Super Mario Bros. 2 as too difficult for American audiences. He’s been asked about almost everything.

So? Bowser?

The Bowser is Bowzer

Here’s the most beautiful part.

Over forty years, Bowser evolved from a one-dimensional fire-breathing villain into the comedy shtick of a 1970s Bowzer:

- The bumbling dad who genuinely loves kids

- The hopeless romantic pining for his girl

- The adversary who holds grudging respect

- The antagonist whose menace is increasingly played for comedy

And in 2023, the apotheosis: Jack Black voicing Bowser in the Super Mario Bros. movie, sitting at a piano, singing a power ballad called “Peaches” about his unrequited love.

It’s as Bowzer as Bowser can get.

The tough guy who sings love songs.

Whether or not anyone at Nintendo in 1985 consciously intended the reference, the character arc rhymes perfectly with its namesake. Bowser became Bowzer. The archetype was encoded in the name from the beginning.

If anyone reading this has contact with Howard Phillips, please ask:

“Did you name Bowser after Sha Na Na?”

The answer might finally close a forty-year-old case that was never actually mysterious. We just forgot to ask the right people the right question, to stop believing it is unknowable.