Dan Lyke asked me a good question today, in response to my Jeep of Death blog post and tweets about patching:

So yay for sharing, but we shouldn’t normalize getting your car patches from random Internet users.

On the one hand it would be easy to agree with Dan’s point. Randomness sounds scary and untrustworthy.

On the other hand, reality says doing safe business with random people might be a reasonable and normal state of affairs. I mean imagine getting a car chip update from a random vendor, or a part to fix your suspension or brakes. Imagine getting fuel from a random vendor.

Can trust or standards of care be established to allow randomness? Yes, obviously. Hello FTC.

My response to Dan was more brief than that response, because, well, Twitter:

why not? we get other “after market” fixes for cars all the time

This does not convince Dan, unfortunately. He asks an even scarier question:

would you run random executables emailed to you by internet strangers? On your car?

I try to explain again what I said before, that we enjoy a market full of randomness that our cars execute already (e.g. gasoline, diesel…steam, vegetable oil). And that is a good thing.

YES. because i have a digital right to repair, i would. i have been doing this on my diesel chip and motorcycles for a decade.

As far as I can tell Ducati was the first to allow after-market software patches on their engines, more than fifteen years ago. I owned a 2001 motorcycle that certainly allowed for it as I patched the ECU about every year, always after-market and sometimes with a random mechanic.

The idea that we should allow any patching process to be wholly controlled by vendors and not at all by consumers or independent mechanics sounds to me like a very dangerous imbalance.

Allow me to explain in more than 140 characters:

Having the right to repair is actually an ancient fight. Anyone familiar with American political history knows horror stories about Standard Oil, Ma’ Bell, let alone GM and Ford; monopolies that have tried to shut-down innovators. Or maybe I should invoke the angry Bill Gate’s hate letter to hobbyists?

Lessons learned from history can be plenty relevant to today’s dilemmas. Consider for example the Right to Repair legislation, that that I last blogged about in 2005, pushed by the late great Senator Wellstone.

The argument made in 2001 by Senator Wellstone was manufacturers established “unfair monopoly” by locking away essential repair information, which prohibited independent mechanics from working on cars.

Wellstone’s ‘Motor Vehicle Owners’ Right to Repair Act’ Gives Vehicle Owners the Right to Choose Where, How and by Whom To Have Repairs and Parts of Their Choice. […] This legislation allows the vehicle owners — and not the car manufacturers — to own the repair and parts information on their personal property, this time their vehicles. It simply allows motoring consumers to have the ability to choose where, how and by whom to have their vehicles repaired and to choose the replacement parts of their choice — even to work on their own vehicles if they choose.

Opposition to the legislation was not only from the big companies that would have to share information with customers. Some outside the companies also argued against transparency and self (or at least independent) services. Believe it or not, for years statements were being made about protecting “high-tech” car security (e.g. passive anti-theft devices such as smart-key and engine immobilizer) with obfuscation.

Of course we know obfuscation to be a weak argument in information security, right? Put recent news about electronic key thieves in perspective of ConsumerReports arguing in the mid 2000s that obfuscation of key technology would better protect consumers from threats…

Well the fight against consumer right to repair cars dragged on and on until Massachusetts politicians broke through the nonsense in 2012 and passed H. 4362, a Right to Repair, which was seen as a compromise that car manufacturers could swallow.

Nearly thirteen years after Wellstone introduced his bill, an important federal step was taken towards normalizing random patches.

The long fight over “right to repair” seems to be nearing an end.

For more than a decade, independent car repair chains such as Jiffy Lube and parts retailers such as AutoZone have been lobbying for laws that would give them standardized access to the diagnostic tools that automakers give their franchised dealers.

Automakers have resisted, citing the cost of software changes required to make the information more accessible.

It was because of a mostly external benefit (consumers), with mostly internal cost (automakers), that regulators had to step in to balance the economics of repair information access. Wellstone was wise to recognize consumer safety from access to information, lower-cost and faster repairs to things they own, could be more beneficial to the auto industry than higher margins.

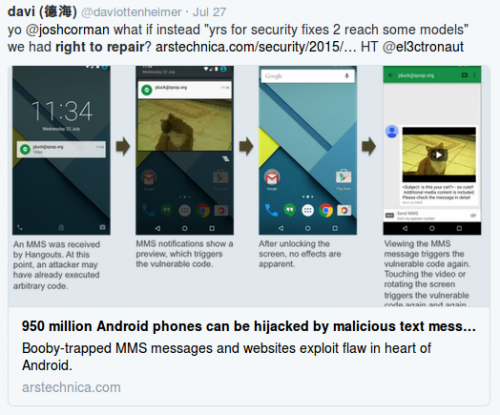

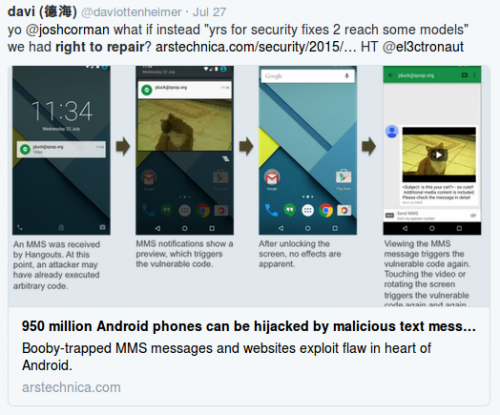

I attempted to translate this political theory into today’s terms by Tweeting at people for a Digital Right to Repair on Android phones.

Perhaps I see the parallels today because I ran security programs at Yahoo! for mobile a decade ago and noticed parallels back then.

Phone manufacturers were slow to push security updates. Consumers were slow to pull updates. It seemed, from a cost-effective risk management view, that allowing Right to Repair to hundreds of millions of consumers we essentially would grease the wheels of progress and improvements. We anticipated patches would roll sooner and where innovation was available, because knowledge.

In other words rules that prevented understanding internals of devices also stalled understanding how to repair. To me that is a very serious security calculation.

What industry needs to discuss specifically is whether the rules to prevent understanding will unreasonably prevent safety protections from forming. Withholding information may push consumers unwittingly into an expensive and dangerous risk scenario that easily could have been avoided. Who should be held responsible when that happens?

Looking forward, the economics of IoT patching (i.e. trillions of devices needing triage) begs why not enhance sharing to leverage local resources for partnership and innovations in self-defense. As we move towards more devices needing repair, I certainly hope we do not lose sight of Wellstone’s legacy and the lessons his Act has taught us.