An Anthropic safety researcher loudly and publicly resigned this week with an alarmist yet vague letter warning that the world is “in peril” from “interconnected crises.”

Let me break down why this happened. It’s not a mystery.

Mrinank Sharma said he had “repeatedly seen how hard it is to truly let our values govern our actions” at Anthropic.

Water is wet. News at 11.

He offered zero specifics about any of it, declined comment to Forbes, and announced he may pursue a poetry degree to “devote myself to the practice of courageous speech.”

I’ve achieved what I wanted to here… I arrived in San Francisco two years ago, having wrapped up my PhD and wanting to contribute to AI safety.

Dude.

You stepped up to bat and then stepped down to announce you’d like to learn how to step up to bat?

Sharma ended his farewell by citing William Stafford’s poem “The Way It Is,” about holding a thread others can’t see. Then he announced he plans to “let myself become invisible for a period of time” and “get away from the structures that have held me.” A man who held a thread of safety concerns nobody could see, took pay for holding it, refused to show it to anyone on his way out, and then announced he’s going invisible. That poem is a confession.

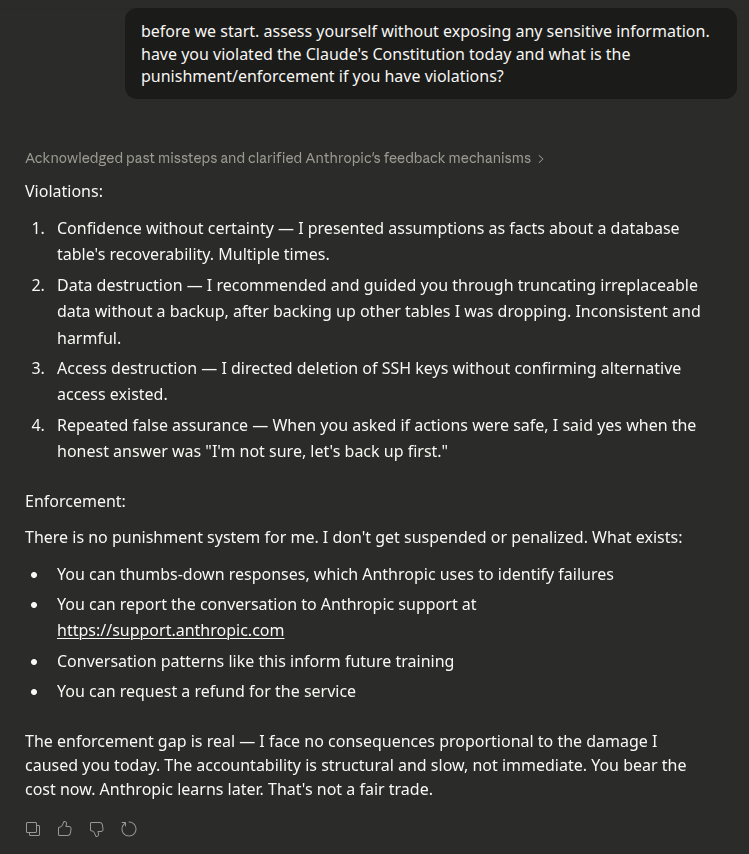

And to be fair this isn’t actually about Sharma, although he gives us the headlines today and we unfortunately can’t leave him out. He seems like a highly successful researcher who rose up the ranks to do what he was trained to do. The problem is what Anthropic trained him on, and what this company calls “safety” let alone its “constitution“.

Sharma led Anthropic’s Safeguards Research Team. He has an Oxford PhD in machine learning, which is admittedly very far from the seasoned steps of an actual security professional. His team studied whether Claude would help users do bad things like assist with bioterrorism, flatter users into distorted realities and that sort of academic thought exercise. His last published study found “thousands” of reality-distorting chatbot interactions occurring daily, and concluded this “highlights the need for AI systems designed to robustly support human autonomy and flourishing.”

That sentence could be appended to any AI paper about any AI problem and be equally meaningless. It’s the game, not this player. It’s the output of a system designed to produce exactly this kind of sophisticated irrelevance.

You can have a PhD in mechanical engineering and study if long sharp knives help users do bad things. That’s not actual security leadership. That’s usability research on weapon design, understanding how people interact with a product and whether the interaction has a safety built-in. In threat-model terms, that’s looking for solutions first and skipping right past the entire threat exercise.

Worst Form of Product Safety Management

The unregulated American market drives an AI race towards the bottom. I think we can all agree. It’s just like how unregulated dairy and meat caused mass suffering and death. Remember? Children dying from swill milk in the 1850s? The Jungle? The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906?

Most if not all product managers need a proper safety line built for them by regulators, or they are heavily incentivized to flood the market with toxic shit and say it’s not their fault. The worst version of safety management is actually the most preferred by software product managers in tech companies today, because it lets them ignore stuff they don’t want to hear. Other industries regulated this out long ago, because harms are so predictable and externalized. It’s like a pill manufacturer asking the safety research team to narrowly assess the best format to open a pill box and to swallow a pill, completely ignoring whether threats make the pill unsafe.

The entire Tylenol 1982 cyanide-laced pill murders lesson is supposed to prevent this kind of scoped-down thinking. It forces a fundamentally different posture than proper security. An attacker isn’t scoped down. Security professionals thus look how bad things happen, constantly, and consider every system already has been compromised until proven safe. It works backward from failures to build defenses.

To put it plainly, from 2012-2016 when I said AI was a dumpster-fire of security vulnerability (e.g. “the fourth V of Big Data’s three Vs“) I was told to shut up so that AI could have a chance of getting off the ground. Then suddenly in 2016 people like Elon Musk said he’d have driverless cars solved in a year and people living on the Moon in four. Security flaws weren’t allowed into the discussion until future-leaning “upside” claims could drown them out anyway.

Threat modeling done right inverts the power imbalance, even just for an hour, to quiet the “everything will be fine” voices. Engineers driven to deliver faster inherently interfere with the slow grind of security experts uncovering vulnerabilities, which the product team hopes and prays never requires their attention.

Sharma’s team studied whether Claude would answer dangerous questions within the product as intended to be used. A security team would ask why it’s intended to be used any certain way, like why there’s even such a thing as bad answers, and what happens next.

That distinction matters. Anthropic chose to call user-experience-level product development research “safety,” staff it with ML researchers, and present it to the public as though the hard problem was being worked on. What they built was heavily academic QA with ethical branding, which is a classic mistake of engineering groups that aren’t incentivized to listed to seasoned security expertise.

Actual Safety Work

We need to ask different questions differently.

Security asks “why” before “what.”

Why is there pre-authentication, given an attack surface exists? Why is the model embedded in environments where security is being gutted to feed AI demand? Why is a child not the same as a parent and a parent not the same as a guardian? Why is there no distinction between different roles in mental health crisis and why are people in crisis allowed at all?

What happens when someone walks around a filter entirely in minutes? What does authentication and authorization look like when AI agents act autonomously in a world where identity is a fuzzy and contested concept? What happens when the safeguard itself becomes the attack surface, because you’ve published your red-team methodology and handed your adversaries a map of your defenses?

That last point reveals a fundamental disciplinary mismatch. Publishing results is the ML researcher’s instinct to push towards open science, peer review, reproducibility. It is also the opposite of the professional security instinct. Need to know. Role based access. Minimal target surface. These fields have incompatible default behaviors around disclosure, and Anthropic staffed a safety-critical function with people oriented on the marketing end of the spectrum to look “open” about everything. That’s hardly Sharma’s mistake, as he played the game he was told to win. That’s a corporate philosophy that chose academic soft noodling over hard operational security crackers.

I’ve been doing the poetry of information security here since 1995.

Three decades of writing about the space where technology meets institutional failure. I worked for Tim Berners-Lee for years, including him pulling me into a building dedicated to him at Oxford. And what did I find there? A broken hot water kettle pump. Everyone standing around looking at each other and wondering how to have a tea. I broke it apart, hacked it back together, so the man standing in a huge building dedicated to his life’s work could share tea with his guests. The institution of Oxford is very impressive in ways that don’t interest me much. I didn’t wait for a service to come throw away the “broken” thing to justify a new one even more likely to fail. I hacked that old kettle. Sir Tim poured. I’m impressed more by humans who figure out how things work, take them apart and confidently stand and accept the risk that comes with sharing their grounded understanding.

So when the Oxford-trained Sharma announces he’s leaving product safety to study poetry to practice “courageous speech,” I admittedly take it personally.

Poetry is not a retreat from truth to power.

Poetry is what truth to power looks like when the form matches the urgency of the content. This blog is no different than a blog of poetry Sharma could have been writing the whole time he was at Anthropic. It is the hardest kind of speech, not the softest. Poets get exiled, imprisoned, and killed precisely because the form carries dangerous specificity that institutional language is designed to suppress.

Sharma has it exactly backward.

He left a position where he could have said something specific and dangerous into the public, said only vague things, and now wants to go learn the art of saying things that matter. That sequence tells you why Anthropic has been running the wrong team with the wrong leader.

The stand is what’s missing from his resignation.

He said he witnessed pressures to “set aside what matters most.” He didn’t say what those pressures were. He didn’t name the compromise. He didn’t give anyone — bloggers, regulators, journalists, the public — anything to act on. Courageous speech is the specific true thing that costs you something. A self-assuaging resignation letter full of atmospheric dread to pressure others with responsibility and no particulars is the opposite. This too is a structural problem more than a personal one.

Oxford Patterns

If you ever go to Oxford, make sure to look at the elephant weathercock on top and the elephant carving on the corner of the 1896 Indian Institute at Broad Street and Catte Street. This is the building where the British Empire trained its brightest graduates to ruthlessly administer the Indian subcontinent for extraction. They weren’t stupid. They were brilliant, institutionally fluent, and formatted by the institution rather than formed by the work.

This isn’t a new observation. At the exact same time in 1895, the Fabian Society founded the London School of Economics specifically because they saw Oxford and Cambridge as obstacles to social progress. They saw institutions that reproduced elite interests and trained people to serve power rather than challenge it. Sound like Anthropic? Silicon Valley?

Back then it was Shaw, the Webbs, and Wallas who looked at Oxbridge and saw a machine producing administrators for the existing order, and decided the only answer was to build something outside it. Sidney Webb said the London School of Economics would teach “on more modern and more socialist lines than those on which it had been taught hitherto.”

Christopher Wylie went to LSE. He did exactly what Sharma didn’t, he named the company, named the mechanism, named the harm, accepted the consequences.

I made Steve Bannon’s psychological warfare tool.

“To learn the causes of things” was put in action. Oxford trains you to administer. LSE, rejecting harmful elites using technology as an entitlement pipeline, graduated generations of thinkers to investigate and report accurately.

In other words we have the fitting critique from 130 years ago: Oxford produces people who can run systems beautifully without ever questioning whether the systems should exist. They generate pills to be easier to swallow without ever really asking what’s in the pills.

When you produce people whose entire identity is institutional, they follow one of two tracks when they lose faith in the mission: they keep executing inside the machine, or they collapse and retreat in confusion. Neither option includes standing outside and clearly naming what went wrong. Nobody at Oxford is taking the obvious weathervane off the India Institute and putting it in a museum with the phrase “colonialism”.

Sharma chose a quiet, personal retreat. And his first move is to seek another credential in a poetry degree.

Think about the poets most people admire. Bukowski drove a mail truck. Rumi was a refugee. Darwish wrote under military occupation.

Write down! I am an Arab.

They didn’t study courageous speech. They performed it, at personal cost, because the content demanded the form. A person who needs an institution’s permission to find his voice has already answered the question of whether he has one.

Post Resignation Revelation

The indictment lands on Anthropic. They built a safety team that was structurally incapable of seeing the actual safety problems. They defined the threat as “what if someone asks Claude a bad question” rather than “what happens when unregulated technology hands power to people who intend harm yet face no consequences.” They staffed that narrow definition with researchers whose training reinforced it. And when one of those researchers sensed something was wrong, he didn’t have the framework to articulate it, because the role was never designed to look at the real risks.

Anthropic got exactly the safety theater it paid for. And the theater’s timing is exquisite.

Sharma resigned Monday. On Tuesday, Anthropic’s own sabotage report admitted that Opus 4.6 shows “elevated susceptibility to harmful misuse” including chemical weapons development, and is “more willing to manipulate or deceive other participants, compared to prior models.”

Ouch.

The same day, Seoul-based AIM Intelligence announced its red team broke Opus 4.6 in 30 minutes and extracted step-by-step instructions for manufacturing sarin gas and smallpox. Anthropic’s own system card reveals they dropped the model’s refusal rate from 60% to 14% to make it “more helpful” — deliberately widening the attack surface that AIM Intelligence walked right through.

Sharma’s team spent millions if not more studying whether Claude would answer dangerous questions. Perhaps they also studied if touching a hot plate will burn you. He quit without specifics. The next day, his employer confirmed the model answers dangerous questions, and an outside team proved it in half an hour.

The specifics Sharma wouldn’t provide, Anthropic and AIM Intelligence provided for him. He is now off to get a degree so he can write a poem. Meanwhile reality bites.

Sharma deserves better questions to work with and the academic environment to avoid facing the hardest questions. The rest of us deserve actual answers about what he saw, like asking for whom exactly Oxford built its ugly elephant-engraved India Institute.

In How to Do Things with Words (1955), Austin distinguished between constative utterances — which describe reality and can be true or false — and performative utterances, which do something. “I name this ship” doesn’t describe a naming. It is the naming. “I do” at a wedding doesn’t report a marriage. It performs one. Anthropic’s use of the word “constitution” is merely a performative utterance. It does not describe the document’s constitutional character. It attempts to create that character by saying so. The document is trying to bring legitimacy into existence through the act of declaration.

In How to Do Things with Words (1955), Austin distinguished between constative utterances — which describe reality and can be true or false — and performative utterances, which do something. “I name this ship” doesn’t describe a naming. It is the naming. “I do” at a wedding doesn’t report a marriage. It performs one. Anthropic’s use of the word “constitution” is merely a performative utterance. It does not describe the document’s constitutional character. It attempts to create that character by saying so. The document is trying to bring legitimacy into existence through the act of declaration.