Nick Bilton is a columnist for the New York Times (NYT). He published a story today called “Keeping Your Car Safe From Electronic Thieves” and I adapted my blog post title from his.

Perhaps you can see why I changed the title slightly from his version. Here are a couple reasons:

First, his story is about things inside a car being at risk, rather than the car itself being unsafe. Second, and more to the point, the “electronic thieves” are not stealing cars as much as opening doors and grabbing what is inside.

That second point is a huge clue to this story. If thieves were “cloning” a car key, making a duplicate, then I suspect we would see different behavior. Perhaps penalties for stealing cars are enough disincentive to keep thieves happy with stealing contents. But I doubt that. More likely is that this is a study in opportunity.

You could read the full article, or I suggest instead you just read his tweets on April 6th for a more interesting version of what led to the story (meant to be read from bottom to top, as Twitter would have you do):

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@ejacqui It looks like it’s a broadcasts a bunch of signals to open the car lock. They cost about $100, apparently.

5 retweets 3 favorites

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@seanbonner @gregcohn @tonx @sacca Fast-forward 10 years and thieves (or pranksters) will be doing this with our homes.

2 retweets 4 favorites

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@tweets_amanda I tried. I ran after them, but they took off. The cops said it’s easy to get online, whatever “it” is.

0 retweets 1 favorite

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@r2r @StevenLevy No. A Toyota Prius. Crazy how insecure this “technology” is.

1 retweet 1 favorite

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@kevin2kelly Yep. Exactly. No broken window, and to a passerby it looks like the thief is in their own car. Scary stuff.

1 retweet 3 favorites

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@StevenLevy Yep. I chased after them, not to tell them off, but to ask what technology they were using. :-)

4 retweets 24 favorites

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@noneck Was watching out the window and saw them do it. (I then ran out and yelled at them, and they took off.)

1 retweet 1 favorite

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@sacca Just did a little research & it’s insane how easy it is to get the device they used. Scary when you think about the connected home.

22 retweets 24 favorites

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@Beaker A Toyota Prius. It was like watching someone slice into butter. That simple.

1 retweet 5 favorites

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@schlaf I chased them down and thought, what’s the point. They’re kids. I really wanted to just ask them about the technology! :-)

3 retweets 22 favorites

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@owen_lystrup Toyota Prius. Don’t get one. Buy an old 1970s car with a key. :-)

3 retweets 10 favorites

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@trammell Yep. Literally just pressed a button and opened the door. It was bizarre and scary when you think about the “connected home”.

12 retweets 22 favorites

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@SubBeck Yelled at them and called the cops. The cops sounded blaze by the whole situation.

2 retweets 4 favorites

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@cowperthwait Toyota Prius. It’s insane that they can literally press a button and open the door.

23 retweets 16 favorites

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

@MatthewKeysLive Nothing; it’s empty. They’ve done it before when I wasn’t around. But I had no idea how they were doing it. Now I know.

3 retweets 5 favorites

Nick Bilton @nickbilton · Apr 6

Just saw 2 kids walk up to my LOCKED car, press a button on a device which unlocked the car, and broke in. So much for our keyless future.

To me there are some fingernails-on-chalkboard annoying tweets in that stream. Horrible attribution, for starters (pun not intended). He says don’t get a Toyota Prius because it must be their fault. Similarly he says our keyless future is over and we should buy something from the 1970s with a key. And then he goes on to attack the idea of a connected home.

This is all complete nonsense.

The attribution is wrong. The advice is wrong. Most of all, the fear of the future is wrong.

Consider that thieves leave a car essentially unharmed (unlike all the smash and grab behavior linked to economic/political issues). This tells us a lot about risk, methods and fixes. It means for example that insurance companies are not likely to be motivated for change. After all, no windows broken and no panels scratched or damaged means no real claims.

In this reporter’s case he even says nothing valuable was in the car. There’s nothing really to tell the police other than someone opened the door and closed it again. A thief who walks up, opens the door, and takes whatever they can from inside the car…this is an encryption/privacy expert’s worst nightmare. This is a lock being silently bypassed with something that amounts to a dreaded escrow or golden key. Given the current encryption debate about backdoors we might have a very interesting story on our hands.

THIS COULD HAVE BEEN A VERY POWERFUL AND PERSONAL STORY OF BEING VIOLATED BY WEAK KEY MANAGEMENT – HOW OUR SOCIETY HAS BEEN LET DOWN BY PRODUCT MANUFACTURERS WHO DON’T CARE ENOUGH ABOUT PROTECTION OF OUR ASSETS. Sadly the NYT misses entirely the significance of their missing the point.

Mind you I tried on April 8th to contact the reporter and add some of this perspective, to indicate the story is really about risk economics and a much broader debate on key management.

Unlike the (dare I say shallow) angle taken by the NYT as something “newsworthy”, a car lock bypass is not new to anyone who pays attention to security or to the mundane reports of people getting their cars broken into. That Winnipeg story I offered the reporter to calm him down is years old. There also were reports in London, Los Angeles and other major city news over the past years describing the same exact scenario and how police and car manufacturers weren’t eager to discuss solutions. The NYT reporter is essentially now stumbling into the same rut.

2013 reports actually followed 2012 news of cars being stolen and disappearing. My guess is the organized crime tools filtered down to the hands of petty criminals and eventually mischievous kids. There is far wider opportunity as motives soften and means become easier. The organization and operation required to fence a stolen car probably shifted first to joy rides, then shifted again to people grabbing contents of cars and eventually to people just curious about weak controls. The shifts happened over years and then, finally, a NYT reporter felt it personally and was rustled awake.

Apparently the NYT did not pay attention to the alarming (pun not intended) trend other reporters have put in their headlines. I did a quick search and found no mention by them before now. It does seem a bit like when crime happens to a NYT reporter the NYT cares much more about the story and frames it as very newsworthy and novel, if you know what I mean.

To really put it in perspective, nearly twenty years ago a colleague of mine had set a personal goal to invisibly open car doors in under five seconds. This is a real thing. He was averaging around seven seconds. General lock picking has since become a more widely known sport with open and popular competitions.

Anyone saying “so much for our keyless future” after this kind of incident arguably has no clue about security in the present let alone the future. Expressing frustration on Twitter turned into expressing frustration at the NYT, which leaves the reader hanging for some real risk analysis.

So that is why I say the real story here, similar to a key escrow angle missed by the reporter, is economics of a fix. Why doesn’t he take a hard look at the incentives and real barriers to build better keyless electronic systems?

The NYT reporter gets so close to the flame and still doesn’t see the problem. For example he mentions that he dug up some researchers (e.g. Aurélien Francillon, Boris Danev and Srdjan Capkun) who had published their work in this area. Isn’t the obvious question then why a key and lock aren’t able yet to fend off an unauthorized signal boost after the problem was detailed in a 2011 paper (PDF): “Relay Attacks on Passive Keyless Entry and Start Systems in Modern Cars“?

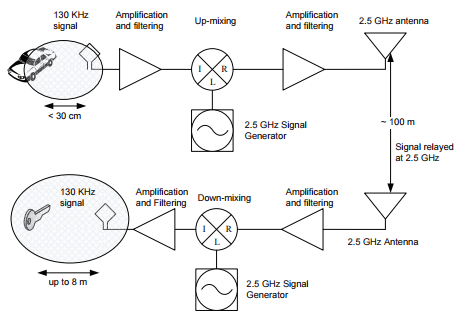

“Figure 4. Simplified view of the attack relaying LF (130 KHz) signals over the air by upconversion and downconversion. The relay is realized in analog to limit processing time.”

Long story short thieves obviously have realized that keyless entry relies on a primitive communication channel, based on near proximity, between lock and key. The thieves may even have inside access to lock development companies and read technical manuals that revealed assumptions like “key must be within x feet for door to unlock”. Some people would stop at x feet but that statement is a huge hint to hackers that they should try to achieve greater ranges than meant to work.

The simple theory, the one that makes the most sense here, is that thieves are simply boosting the signal to extend the range of keyless entry signal.

First they pull a car door handle, which initiates a key request. Normally the key would be out of range but thieves boost the request much further away. The key could be in the owners pocket inside a restaurant, or a school, on a baseball field, at a park bench, or even in a home.

Second the key receives the door signal and sends its reply.

Third the thieves pull the door handle to open the car.

Simple no?

One might suppose the thieves could press a start button and drive away but then what happens when they shut the engine off many miles from the key? That’s a whole different level of thief as I mentioned above. Proximity means risk/complexity of an attack is lowest if they just invisibly open a door and take small-value items or nothing at all.

Again, insurance companies are not going to jump into this without damage to a car or the car isn’t stolen. Manufacturers likewise have little incentive to fix the issue if there is no damage. A more viable solution, thinking about the economics and market forces, would be to encourage car owners to buy an aftermarket upgrade based on standards.

Don’t like the stereo in your car? Put in a better one aftermarket. Don’t like the seats? Upgrade those too, with better seat belts and lumbar support. Upgrade the brakes, the suspension and even put in an alarm…now ask yourself if you can find a new set of quality electronic locks that blocks the latest attacks. Where is that market?

Isn’t it strange that you can not simply upgrade to a better electronic lock? It sounds weird, right? Where would you go to get a better key system for your car? The platform, the car itself, should allow you to upgrade to an electronic key. Add a simple on/off switch and this attack would be defeated. This would be like installing better locks and keys in your home (explaining why our homes are not at the same level of risk from this attack). Why can’t you do this for a car?

That is the real question that a reporter in the NYT should have been asking people. Instead he found someone who suggested putting his key into a Faraday cage (blocking signals).

So now he has the bright idea to put his key in the freezer at home with the ice cream.

That shows a fundamentally flawed understanding and defeatist security. Who wants to keep their car at home to be safe because they can’t carry a freezer around everywhere. A metal box or even mylar bag would have been at least a nod in the right direction, to safely parking your car somewhere besides home.

Basically the NYT reporter over-reacts and then pats himself on the back with a silly and ineffective band-aid story. He misses entirely the opportunity to take a serious inquiry into why car manufacturers have been quiet about a long-time key management problem. Perhaps my Tweets were able to sway him towards realizing this is not as novel as he first thought.

Even better would have been if the reporter had been swayed to research why manufacturers use obfuscation instead of opening key management to a standard and free platform for innovation, supporting the safety advances from lock pick competitions. This issue is not about a Prius, a Toyota or even scary electronics entering our world. It is really about risk economics, policy and consumer rights.