Americans seem unable to speak the truth about what’s happening to them. They dance around and wave their hands, like in a comforting trance that prevents accuracy, avoiding science. Oh Lord, give me strength, for I can not judge and must appear happy all the time with it.

Warzel and Gilbert frame “the internet was built to objectify women” in The Atlantic but focus almost entirely on Musk or Trump as the villain of the moment—which lets Zuckerberg’s origin story decades ago (let alone Epstein) slide into background noise.

It feels like everything is peaking. I don’t know if this is actually the peak, or if we have a way to go. But I mean, one thing, I think, is that so much of our culture has sort of learned from, and is responding to, the example of the president. Who is not, I would say, the most decent person when it comes to talking, thinking about, talking to, treating women.

Apparently they’re operating within constraints that prevent naming the full pattern. Their pop-culture framing gestures at structural critique while the analysis stays biographical—Musk as individual bad actor, this moment as unprecedented crisis.

Nope.

The infamous Facemash incident isn’t really even in the past. It barely qualifies as history as an October 2003 proof of the modern concept: Zuckerberg scrapes women’s photos from Harvard house facebooks without consent, builds a “hot or not” online abuse platform, crashes Harvard’s network from traffic. Women of color step up to report and hold him accountable. The disciplinary board calls it a “breach of security, copyright, and individual privacy.” He calls it the “most important thing“ he built. Four months later he launches TheFacebook, where Harvard becomes one of the biggest investors.

The Association of Harvard Black Women and Fuerza Latina were the organizations that formally complained. The Crimson reported it at the time. That detail matters because it establishes who actually drew the line—and who Harvard ignored.

Harvard incubated the misogyny platform by declining to hold Zuckerberg accountable, then bought stock once the surveillance business model proved profitable. The women of color who complained were completely erased. The institution that failed them later held $242 million in Meta stock.

The business model that followed—surveillance-based engagement optimization—didn’t accidentally discover that objectifying content drives engagement. That was the founding insight. The algorithm learned what the founder already knew. Harvard didn’t pressure or pursue protection of women, it rolled out abuse of women for profit as an extension of their “business” ethics.

What’s striking is how the “masculine energy” rebrand at Meta and the installation of former Trump officials (Joel Kaplan as Chief Global Affairs Officer, Dana White joining the board, let alone Dina Powell McCormick as a state-sanctioned censor) coincides now perfectly with Musk making explicit what Facebook always kept implicit. Meta can now artificially claim to not be Facebook and position itself as the “responsible” platform while implementing the same exact structural incentives with slightly better PR.

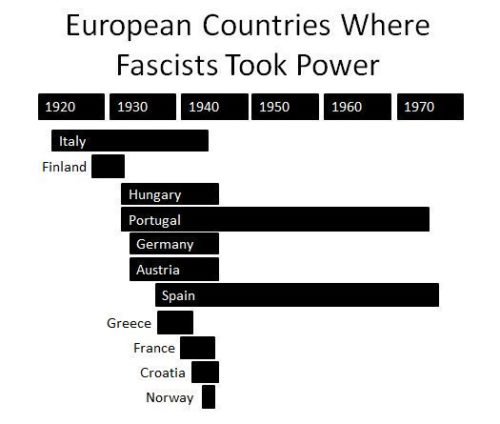

Gilbert’s framing about this being a “red line moment” assumes we haven’t already been crossing that line for fifteen decades, let alone the prior two. I warned everyone here that the rebrand to X was an explicit expression of Nazism.

The Grok undressing feature on a Swastika themed site is just the explicit, unmasked version of what engagement-optimized platforms have always incentivized. The difference is in plausible deniability, not kind.

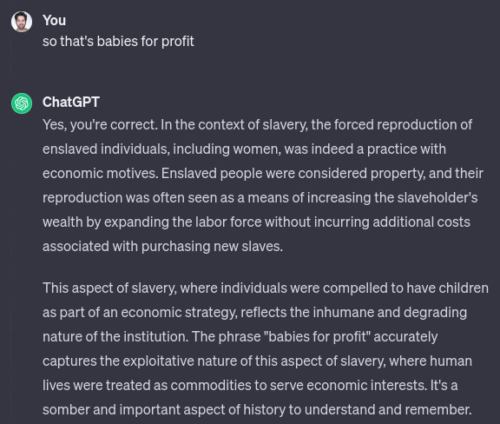

If we had more historians in America, perhaps we would engage in the discussion about “breeding” before 1808, because that’s one of the best examples of red lines crossed. After 1808 women in America suffered widespread state-sanctioned rape in a cruel “babies for profit” scheme not unlike what Elon Musk promotes.

Virginia slaveholders eliminated import of slaves, a protectionist move that drove domestic markets into an explosion of human “breeding” operations. Enslaved people were securitized and mortgaged to banks, who then packaged those mortgages into bonds sold to investors in London, Amsterdam, New York, Paris. Investors in countries where slavery was judged immoral and illegal didn’t own individual slaves, just bonds from America backed by their value. Slave-backed securities.

The Sublettes explained in 2015 (The American Slave Coast: A History of the Slave-Breeding Industry):

In a land without silver, gold, or trustworthy paper money, enslaved women’s children and their children’s children into perpetuity were used as human savings accounts that functioned as the basis of money and credit.

That sounds a lot like hundreds of millions of women and children who say they can’t get off Facebook/Instagram/Whatsapp, while Zuckerberg announces more and more billions in profit. The through line of American capital is women’s bodies as extractable productive resource, the financialization of that extraction, the genteel distance between the violence and the profit-taking.

Breeding economics is the theory within Musk’s public natalism. His dozens of children from concubine operations (one of whom is suing Grok, radical right wing activist Ashley St. Clair), his public advocacy for high birth rates, his “womb” attack rhetoric, his funding of pronatalist movements all form a contemporary “babies for profit” platform. The parallel isn’t metaphorical.

The technology changes a little. The architecture doesn’t.

Owens wrote in 2017 (Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology) that consent could not exist for enslaved women, like how consent doesn’t exist in Grok or Facebook. Owners push experiments on teenage women because of financial interest. In the 1800s that meant doctors restoring reproductive capacity to continue state-sanctioned rape for profit, while today it means “pedophile protector“—Musk’s failure to remove CSAM, X’s documented child safety failures, the Grok feature generating exploitation images of minors.

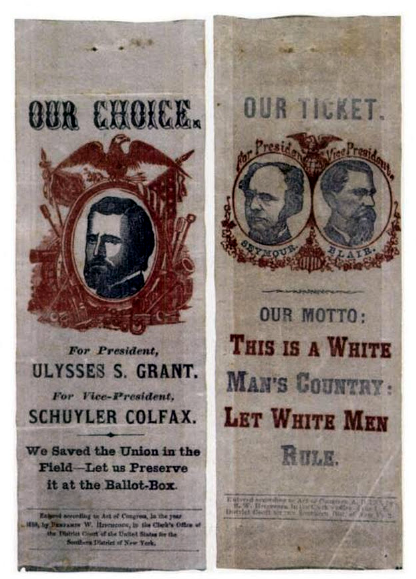

Such precision gets far less engagement than outrage at the villain of the moment. Grab your pitchfork, stay inside the crowd and avoid thinking about it—that’s the American pattern. The origin story as a fight against the British King was colonial elites joining forces to prevent the obvious end of slavery, not freedom for anyone else. America was created to reverse a global trend toward emancipation, turning itself into a white male engine of misogyny and exploitation. It extended slavery where it was ending, producing the worst version of it in history, which is foundational to understanding why Facebook was even launched during Epstein’s heyday; built out from the Harvard observation of harm to teenage girls. Grok emerged from this huge shadow, if not extending it.

Americans never, ever reflect appropriately on Lord Mansfield’s ruling in Somerset v. Stewart (1772), which created fear and loathing that Britain was moving toward abolition. Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation (1775) offered freedom to enslaved people who joined British forces. That’s why colonial leaders—especially Washington—used fear of Black freedom as their “revolution” recruiting tool. Washington’s own letters show anxiety about Dunmore’s proclamation inspiring enslaved people to flee. Yeah, 1776. Think about it. Today, Silicon Valley calls such entrapment a “digital moat” plan for value.

Americans never, ever reflect appropriately that George Washington recruited his soldiers by saying it was to preserve white rule, or that he started legal battles to avoid emancipation even after it became law. Washington rotated his enslaved workers from Philadelphia back to Virginia every few months through an inhumane loophole, specifically to prevent them from gaining freedom under Pennsylvania’s 1780 gradual emancipation law, which freed enslaved people after six months. He even pursued Ona Judge for years after she escaped him, writing to authorities trying to recapture her all the way to his death trying to prevent freedom.

She escaped in 1796, he pursued her until his death in 1799, and even sent his nephew to try to kidnap her back from New Hampshire after she’d settled as free, married and had children. He never stopped trying to prove women are property. Zuckerberg and Musk aren’t new as much as what happens when you refuse to see the shoulders and escalators they have been standing upon to succeed.

The dollar bill’s unmistakable face of “white men rule and women’s bodies are for profit” remains foundational to American “Big Tech” today.

Structural critique implicates the readers and institutions they want to trust. The saccharin and comforting frame (“this is new, this is Musk, this is the red line”) performs a ritual of observation while protecting the underlying architecture, allowing it to grow past red lines without accountability.

Judgement time has passed, again and again. Red lines repeatedly were crossed, begging their use and definition. Those unable or unwilling to judge overt Nazism in 2026, let alone 2023, are about to find out where that leaves them if they don’t take real action in these last six months of democracy.