I remember well in the mid 1990s how a professor of physics demanded that a university save money purchasing computers. His theory was that one or maybe even two extra PCs would be available in a lab with money saved.

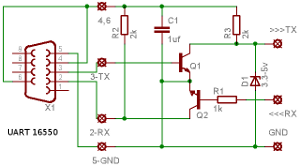

The problem with his theory was that the less-expensive computers experienced a high rate of malfunction and failure. The computers were purchased specifically to perform lab work using devices connected to a serial port. The serial port depended on a 16550 Universal Asynchronous Receiver/Transmitter (UART) chip.

At that time Gateway 2000 was saving money by using the least expensive parts available. An order of fifteen PCs could end up with fifteen different UART brands and/or versions, many of which would fail under load. More specifically we suspected that a single character would get left in a shift register and one in the holding register; the character then would not transmit and give no interrupt or alert. System failure.

It was not possible to determine through software the revision of the chip installed so drivers could not compensate and adapt to this problem. The solution, at that time after meetings and evaluation of PC vendors, was to dump the Gateway investment and purchase Dell “business-line” computers — the OptiPlex. Dell offered the university a guarantee of chip quality control and consistency, which actually turned out to be the case for the UART.

The bottom line was that more money was saved by high availability in just one semester than by the lower initial capital investment.

Apparently the same could not be said for capacitors.

Engadget does not mince words in a recent report regarding the OptiPlex:

Dell asked customer service reps to deny there was any problem with their motherboards, telling them to pretend they’d never heard about the issue and to “emphasize uncertainty.”

Uncertainly is exactly what consumers should be trying to avoid.

An earlier post on Engadget suggests a 97% failure rate!

According to recently released documents stemming from a three year-old lawsuit, Dell not only knew about the bogus components but some of its employees were actively told to play dumb, one memo sent to customer service reps telling them to “avoid all language indicating the boards were bad or had issues.” Meanwhile, sales teams were still selling funky OptiPlex machines, which during that period had a 97 percent failure rate according to Dell’s own study.

To be fair that still leaves a 3% chance of success — uncertainty isn’t gone yet.

Imagine 3% of an office working, or 3% of a student body getting their work done…

This is not just a problem with Dell or Gateway, of course. All manufacturers of technology equipment face the question of quality when building their products.

I noticed the D-Link DWL-3200AP, for example, was using low-ESR capacitor rated for only 1000 hours. This seems far below the normal use one might expect from a wireless bridge. Anyone could go buy a 7000-hour high-temp capacitor for less than a quarter.

Likewise, I found that the Motorola 2210-02 ADSL2+ broadband modem has a capacitor that fails due to load. It overheats and then shuts down the broadband link (perhaps you were wondering why this site went down for a day or two last month — thank you for the hits, and for exposing a hardware failure in my infrastructure). This is only marginally better than complete failure. It masks the cause by being intermittent, which is worse. Once I found the problem I was able to keep the link up by removing heat, which is why it is better.

Oh, and do not get me started on Apple hardware failures. I am on my third (and last) iPhone in only six months. The most recent failure was caused by a bad cable. Who puts six ribbon cables in a phone? This is a device that is totally sealed to consumers and constantly moved around. Ribbon cables are known to come loose. Put the two risk factors together…my phone was unsuable for two days (screen had limited functionality) and I spent two hours at an Apple store just to get the cable re-seated.

I would gladly have paid an extra dollar or two to avoid the multi-day outage. Two antenna cables, three data cables, and a screen cable; in other words, six too many:

The lesson seems to be that hardware quality continues to plague network devices with serious security (availability) consequences.

Product companies make decisions that might not reflect your requirements, but they also do not give much transparency prior to the purchase or readily accept fault afterwards. Buyer beware.

Here are a few suggestions for how to reduce hardware risks:

- Test – We would have found the UART failure quickly if we had just ordered one or two systems and run them through the paces

- Contract – Make certain that a failure of hardware is covered with warranty and perhaps even compensation

- Virtualize – Isolate hardware to a single highly-redundant device and then put the other devices into a virtual environment were you have more control and better logging options