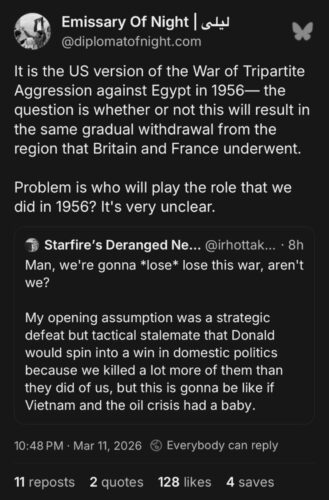

A thread on Bluesky was forwarded to me that compared the US-Israeli war on Iran to the 1956 Suez Crisis, or the “War of Tripartite Aggression” as it’s called by some.

Their argument is we are in America’s Suez moment, and the question is who forces the withdrawal the way Eisenhower forced Britain and France out of Egypt.

It’s wrong. The parallel doesn’t fit. And the reason it’s wrong is far more dangerous if people keep seeing 1956.

1956 Crisis Was Remarkable for the End

President Eisenhower, a seasoned WWII military general, had the motivation and leverage to end the conflict in Suez. That sentence contains two requirements, not one, and both were specific to the architecture of the postwar order.

Eisenhower had personally spent a decade building the global security structure that American hegemony depended on: NATO, SEATO, Bretton Woods, the dollar as reserve currency, bilateral defense agreements across the Middle East. All of it rested on the structural premise that the United States was the sole legitimate authority over when Western military force gets deployed. He led the Allied defeat of Nazi Germany and in history stands as the exact antithesis to Trump.

Britain and France going into Egypt without American authorization wasn’t a policy disagreement. It was an attempt by weakened rival powers trying to reassert colonial-era authority by making war decisions inside the American security perimeter.

If that precedent stood, the entire modern “united” architecture of nations was negotiable.

Eisenhower also had a Soviet timing problem. The Suez invasion came the same week as a dramatic Soviet invasion of Hungary. Eisenhower wanted Hungary for optics to fracture Soviet legitimacy. He could have said look at what empire does, look at the tanks in Budapest, except his own allies were running a colonial invasion in Egypt.

The moral framework justifying the entire Cold War strategy collapsed if the “good” guys were as bad or worse than the Soviets.

The American President flexed, hard, to put the British and French back in their seats. He threatened to dump Britain’s sterling reserves and block IMF support. The threat was specific, credible, and existential to the British economy, from the man who had saved Britain from Hitler. Eden folded within days. Britain and France withdrew. Eisenhower took a moral stand against Germany (he was directly responsible for documentation of the Holocaust) and pivoted it into the definitive end of European colonial military power in the Middle East.

The key word in all of this is architect. Whether or not Eisenhower acted on principle, he was protecting the law and order building he had built. The rules-based international order, which meant the American-dominated order as a result of WWII, was his structure to keep the world spinning safely. He was compassionate, brave and intelligent but more important to history he was willing to defend the laws of conflict.

No Eisenhower Today

The Suez model requires someone who built something, or owns it now, and is willing to sacrifice to protect it. Who stops Trump from repeatedly committing crimes? Look at who holds leverage today and ask whether either condition is met.

China has the most obvious card. They hold over $750 billion in US Treasuries. They’re the manufacturing backbone of the American consumer economy. Iran is already letting Chinese ships through the Strait of Hormuz while blocking Western ones. Beijing owns a mediator’s position without asking for it, and they aren’t saying much. Perhaps they are learning too much about American weakness to stop America from revealing themselves. They could tell Washington: we’ll keep the Strait open for everyone through our relationship with Tehran, but the price is you stop. The problem is for every F-15E shot down by friendly fire, for every American military facility bombed by Iranian drones, China gains invaluable intelligence to defeat an overextended and over budget America.

China also wants a different architecture, not the preservation of this one. They’d play the Eisenhower card to extract concessions, not to restore systemic stability. That makes them a transactional actor, not a global architectural one. Eisenhower sacrificed the special relationship with Britain to protect the legal system of conflict resolution. China is a competitor that would sacrifice the system to improve its position within it.

The EU has the more structurally Eisenhower-shaped tool. The dollar’s reserve currency status depends on European financial institutions continuing to clear through it. If the ECB and European banks started building euro-denominated energy settlement infrastructure, which the Hormuz crisis is practically begging them to do, that’s the slow-motion version of Eisenhower’s sterling threat. Not a dramatic sell-off, but a structural migration that Washington can’t reverse once it starts. We already have seen EU institutional investors unhitch their wagons from Trump.

The European project is, in principle, an architectural bet. The whole thing is a rules-based order scaled to a continent. But the EU spent seventy years subcontracting its security architecture to Washington as a foundation. Using Eisenhower’s leverage means admitting that the contractor went nuts and you need to rebuild it yourself. That’s not a diplomatic adjustment. That’s a civilizational decision, and nothing in the current European leadership suggests that appetite exists beyond rhetoric. Don’t vacation in NYC. Stop using Google. Ok.

So neither has both requirements. China has leverage without architectural motivation. The EU has architectural identity without the urge to use its leverage. And neither has what Eisenhower had most essentially: the position of the expert builder, someone who treats the international order as their own very specific work product rather than something they inherited or hope to replace.

This Is 1940, Not 1956

If 1956 is the model where an architect intervenes, 1940 is the model where nobody does, meaning everyone gets dragged in by the gravity of their own dependencies.

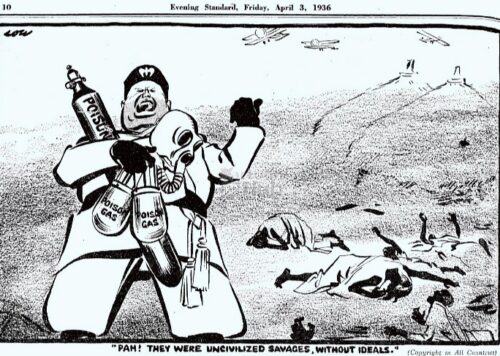

Nobody was motivated to enter a North Africa theater, except Mussolini. Not Hitler. Not the British, who planned a five-day raid and got a three-year campaign. Not the Australians, New Zealanders, South Africans, Indians, or Free French who fought there. The theater emerged because Mussolini was a horrible impatient fraud who created a cascading failure that no single power had the authority or motivation to stop. Every subsequent actor entered not by choice but by compulsion to stabilize the inherent chaos of fascism. Germany couldn’t let Italy collapse. Britain couldn’t let Egypt fall. The Commonwealth couldn’t let Britain fight alone. The United States couldn’t let the Mediterranean become an Axis lake. And the lesson of Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 hung over all of it; the League of Nations’ failure to act then made the cascading drag-in inevitable later.

That’s the pattern unfolding now.

Iran retaliates against Gulf states that hosted American assets. Qatar stops gas production and declares force majeure. Oil hits $119. European energy security is threatened for the second time in four years. The E3 deploy “defensive” military assets to the region. Insurance companies close the Strait of Hormuz more effectively than the Iranian navy did. China gets preferential transit. Japan begs for strategic reserve releases. Qatar’s energy minister warns that continued war will “bring down economies of the world.”

Every actor is being dragged in by dependencies on stability, not by choice to fight for order. That is the key structure of 1940, unlike 1956.

Builder, Tenant, Arsonist

The reason the Suez parallel attracts is (besides more recent) that it implies a resolution mechanism. Somewhere out there is a hero, a responsible adult with leverage who will call a halt to stupidity of Trump’s toddler-like rants. But the 1956 resolution depended on a specific power relationship and rational actors: the aggressor (Britain) was a junior partner dependent on the intervener (the US). Eisenhower could discipline Eden because Eden needed American financial support to survive, and Eden arguably wasn’t someone who would put an Elon Musk in charge of anything and show up in the Epstein Files.

Trump isn’t even close to being an Eden. He can’t be disciplined by a senior partner because his entire existence is proof he never listens. He’s Mussolini in many ways, the deranged hot-headed initiator whose failures create cascading obligations for everyone else. And Netanyahu isn’t playing a subordinate role that can be overruled from above. He’s the catalyst who understood, correctly, that once the war starts, American sunk costs make withdrawal politically impossible. The junior partner traps the senior partner by making the senior partner’s credibility dependent on the junior partner’s war.

This is exactly how Mussolini and Hitler came to entrench in failures. Italy’s North Africa disaster pulled Germany sideways. If the southern Mediterranean fell, the entire Axis position was open to attack. Hitler committed the Afrika Korps not because it was a German strategy but because Mussolini dragged him. The dependency ran upward.

Someone on Bluesky described the likely outcome as “if Vietnam and the oil crisis had a baby.” That captures the domestic experience of quagmire plus economic shock. Yet the structural model remains 1940: a cascading multi-actor catastrophe where the war becomes everyone’s problem not because anyone decided to make it stop, but because the interdependencies won’t let anyone walk away.

The Slide

I studied this dynamic at the LSE under Professor John Kent in the History department. One of Kent’s major works, British Imperial Strategy and the Origins of the Cold War 1944-49, documented the process by which systemic architectural ownership transfers. He laid out that it only transfers when someone wants the outcome badly enough to pay for it.

His core thesis was that the Cold War’s origins weren’t simply US-Soviet ideological confrontation. They were about the collapse of British imperial architecture and the contest over who would replace it. Britain in 1944-49 was trying to maintain its role as systemic guarantor of the Middle Eastern and Mediterranean security order. This was not out of nostalgia, but because the architecture of British global power ran through Suez, the Gulf, and the Eastern Mediterranean.

I unfortunately remember well trying in a seminar, as a young and dumb student, to convince Professor Kent that America was motivated by oil. Pssshaw he said, warning me sternly that Americans don’t read enough to know their own history, in between bites of a cucumber and cream cheese sandwich.

When Britain couldn’t afford to maintain their role (still struggling from WWII), the US stepped in not out of principle but because the vacuum threatened American interests. Truman took over the British position in Greece and Turkey in 1947 because the alternative was Soviet influence in the Eastern Mediterranean. Eisenhower could discipline Eden at Suez in 1956 precisely because the US had already replaced Britain as the architect. Eden was a tenant trying to act like a boss, and Eisenhower reminded him of the global end of white supremacist doctrines.

Kent’s framework makes the current absence explicit. The Eisenhower moment at Suez wasn’t a one-off act of statesmanship. It was the culmination of a decade-long architectural transfer. And the reason there’s no Eisenhower now is that no equivalent transfer has happened. Nobody has taken ownership of the system the US was supposed to still be capable of running, instead of currently setting itself on fire.

The question Kent taught us to ask wasn’t “why do wars start” but “why do wars spread.” The answer, over and over, is that wars spread when the costs of intervention are high but the costs of non-intervention are structurally higher. Every actor faces a local calculation that makes joining cheaper than staying out, even though the aggregate result is catastrophic for everyone.

That’s where we are. The EU can’t afford another energy crisis but can’t afford to break with Washington. China can’t afford Middle Eastern instability but can’t afford to confront the US directly. Gulf states can’t afford Iranian retaliation but can’t afford to deny the US basing rights. Iran can’t afford to keep fighting but can’t afford to stop while bombs are falling. Everyone’s local logic says “keep going.” Nobody’s structural position says “stop.” That’s a 1940 slide again.

In 1956, one man could stop it because he had built the system and valued it more than any single relationship within it. In 1940, nobody could stop it because nobody had built anything they valued more than their own survival. The system didn’t have an architect. It just had tenants looking around for help while their building was being set on fire.

Mussolini always talked like Trump or even Pete Hegseth. It’s easy, it’s ahead of schedule, breaking all the rules means finishing faster. None of that was or is true. Italy sleepwalked into a three-year, multi-nation war across North Africa and lost everything. Mussolini planned a quick advance to Sidi Barrani. He was hanged.