Does encryption prevent crime?

Recently I wrote of how the ANC used encryption to help defeat apartheid rule in South Africa. Looking back at that example being on the right side of history meant being on the wrong side of a law, which ultimately meant committing a crime to prevent a crime. Privacy from surveillance was essential to creating change (e.g. ending the crime of apartheid) because a lack of privacy could mean arrest, imprisonment or even death. So yes, we can point to an example where encryption prevented crime, by enabling crime.

Confused?

When we hear encryption prevents crime we probably need to ask for hard evidence to give us perspective or context. Rather than look at a rather complex issue case by case by case, I wonder if a larger body of work already is available. Has anyone written studies of how encryption prevents crime across the board, over time? Although I have searched far and wide, nothing has appeared so far. Please comment below or contact me if you know of such a study.

A good example of where I have searched is the Workshop on the Economics of Information Security (WEIS). It has many great resources and links, with well-known cryptographers studying social issues. I thought for sure it would have at least several titles on this topic. Yet so far I have not uncovered any vetted research on the economics of preventing crime with encryption.

We may be left for now pulling from examples, specific qualitative cases, such as the ANC. Here is a contemporary one to contemplate: TJX used encryption for wireless communication, and yet ended up having their encryption cited as a major reason for breach, as explained by the Privacy Commissioner of Canada.

The point here is that, despite a fair number of qualitative technical assessments, we seem to lack quantitative study of benefits to crime fighting from encryption. We also lack nuance in how we talk about the use of encryption, which is why you might hear people claim “encryption is either on or off”. That binary thinking obviously does us no favors. Saying the lock is either open or closed doesn’t get at the true issue of whether a lock is capable of stopping crime. Encryption at TJX was on, and yet it was not strong enough to stop crime.

Another good example of where I have searched is the Verizon Breach report, arguably the best breach analysis in our industry. Unfortunately even those thorough researchers have not yet looked into the data to reveal encryption’s effect on crime.

What I am getting at is we probably should not passively accept people making claims about crime being solved, as if true and a foregone conclusion without supporting evidence. Let us see data and analysis of encryption solving crime.

While searching for studies I did find a 2015 Slate article that told readers encryption prevents “millions of crimes”. Bold claim.

…default encryption on smartphones will prevent millions of crimes, including one of the most prevalent crimes in modern society: smartphone theft. In the long run, widespread smartphone encryption will ultimately preserve law and order far more than it will undermine it.

Here is why I think it could be better to challenge these statements instead of letting them slip through. The author arrived at this conclusion through sleight of hand, blurring encryption with data from studies that say a “kill switch” option has been linked to lower rates of physical theft. These studies do not have data on encryption. Protip: encryption and kill switch are very different things. Not the same thing at all and data from one is not transferable to the other. Then, as if we simply swallowed without protest two very different things being served as equivalent, the author brings up ways that a kill switch can fail and therefore is inferior to encryption.

In logic terms it would be A solves for C, therefore use B to solve for C. And on top of that B is better than A because D. This is roughly like:

A: pizza solves C: hunger

B: therefore use water to solve for C: hunger

A: pizza gets soggy when wet, therefore B: water best to solve C: hunger because D: doesn’t get soggy

A careful reader should wonder why something designed to preserve and protect data from theft (encryption) is substituted directly for something designed to make a physical device “unattractive” to re-sellers (kill switch), which may not be related at all to data theft.

…kill switches—even if turned on by default—have serious shortcomings that default encryption doesn’t. First, the consumer has to actually choose to flip the switch and brick the phone after it’s been stolen. Second, the signal instructing the smartphone to lock itself actually has to reach the phone. That can’t happen if the crooks just turn the phone off and then take some trivial steps to block the signal, or ship the phone out of the country, before turning the phone back on to reformat it for resale. (Smartphone theft is increasingly an international affair for which kill switches are not a silver bullet.) And finally, enterprising hackers are always working to provide black market software solutions to bypass the locks, which is one of the reasons why there is a thriving market for even locked smartphones, as demonstrated by a quick search on eBay. Those same hackers, however, would be decisively blocked by a strong default encryption solution.

That last line is nonsense. If nothing else this should kill the article’s credibility on encryption’s role in solving crime. Hard to believe someone would say enterprising hackers always work to bypass locks in one sentence and then next say that “strong default encryption” is immune to these same enterprising hackers. Who believes hackers would be “decisively blocked” because someone said the word “strong” for either locks or encryption? Last year’s strong default encryption could be next year’s equivalent to easily bypassed.

What really is being described in the article is a kill switch becomes more effective using encryption, because the switch is less easily bypassed (encryption helps protects the switch from tampering). That is a good theory. No one should assume we can replace a kill switch with encryption and expect a straight risk equivalency. While encryption helps the kill switch, the reverse also is true. A switch actually can make encryption far safer by erasing the key remotely or on failed logins, for example. Encryption can be far stronger if access to it can be “killed”.

Does installing encryption by itself on a device make hardware unattractive to re-sellers? Only if data is what the attackers are after. Most studies of cell phone theft are looking at the type of crime where grab-and-run is profitable because of a device resale market, not data theft. Otherwise encryption could actually translate to higher rate of thefts because a device could be sold without risk of exposing privacy information. It actually reduces risk to thieves if they aren’t able to get at the data and can just sell the device as clean, potentially making theft more lucrative. Would that increase crime because of encryption? Just a thought. Here’s another one: what if attackers use encryption to lock victims out of their own devices, and then demand a ransom to unlock? Does encryption then get blamed for increasing crime?

Slate pivots and twists in their analysis, blurring physical theft (selling iPhones on eBay) with data theft (selling identity or personal information), without really thinking about the weirdness of real-world economics. More importantly, they bring up several tangential concepts and theories, yet do not offer a single study focused on how encryption has reduced crime. Here’s a perfect example of what I mean by tangential.

As one fascinating study by the security company Symantec demonstrated, phone thieves will almost certainly go after the data on your stolen phone in addition to or instead of just trying to profit from sale of the hardware itself. In that study, Symantec deliberately “lost” 50 identical cellphones stocked with a variety of personal and business apps and data, then studied how the people who found the unsecured phones interacted with them. The upshot of the study: Almost everyone who got hold of one of the phones went straight for the personal information stored on that phone. Ninety-five percent of the people who picked up a phone tried to access personal or sensitive information, or online services like banking or email. Yet only half of those people made any attempt to return the phone—even though the owner’s phone number and email address were clearly marked in the contacts app.

What is fascinating to me is the number of times encryption or crypto appears in that study: zero. Not even once.

Symantec did not turn on encryption to see if any of the results changed. That study definitely is not about encryption helping or hurting crime. Can we try to extrapolate? Would people try harder to access data once they realize it is encrypted, being the curious types, looking for a key or guessing a PIN? Would attempts to return phones go down from half to zero when contact information is encrypted and can’t be read, causing overall phone loss numbers to go up?

And yet clearly the Slate author would have us believe Symantec’s study, which does not include encryption, proves encryption will help. The author gets even bolder from there, jumping to conclusions like this one, a perfect example of what I mean by jumping.

There wouldn’t have been a breach at all if that information had been encrypted.

If encryption, then no more breach…Hey, I think I get it!

- Collect Encrypted Underpants

- ?

- Profit!

No. This is all so wrong. Look again at the TJX breach I mentioned earlier. Look especially at the part where encryption was “in place” when the breach happened.

TJX was using encryption technology for wireless networking, known generally as WEP, that used the RC4 stream cipher for confidentiality and CRC-32 checksum for integrity. There’s the encryption, right there, in the middle of a report discussing a huge, industry changing breach. Despite encryption, or arguably even because of misuse/overconfidence in weak encryption, we saw one of the largest breaches in history. Again, the crux of the issue is we aren’t using nuance in our discussion of encryption “solving” crimes. Far more detail and research of real-world applied encryption is greatly preferred to people saying “encryption is good, prevents crime” dropping the mike and walking off stage.

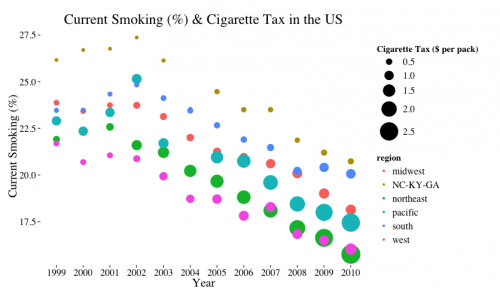

Studies of encryption effects on crime beg details of how we would define levels of “strong”, what is “proper” key management, “gaps” between architecture and operation…but my point again is we don’t seem to have any studies that tell us where, when or how exactly encryption prevented crimes generally, let alone a prediction for our future. Say for example we treat encryption as a tax on threats, an additional cost for them to be successful. Can we model a decline in attacks over time? I would love to see evidence that higher taxes lower likelihood of threats across time compared to lower taxes (e.g. as has been illustrated with US cigarette policies):

We know encryption can prevent types of crime. We no longer have an apartheid government in South Africa, proving a particular control has utility for a specific issue. I just find it interesting how easily people want to use a carte blanche argument for general crime being solved, greater good, when we talk about encryption. People call on us to sign a big encryption check, despite offering no real study or analysis of impact at a macro or quantitative level. That probably should change before we get into policy-level debates about the right or wrong thing to do with regulation of encryption.

Updated to add reference:

“Target Intelligence Committee.” The project, which was originally conceived by Colonel George A. Bicher, Director of the Signal Intelligence Division, ETOUSA, in the summer of 1944, aimed at the investigation and possible exploitation of German cryptologic organizations, operations, installations, and personnel, as soon as possible after the

impending collapse of the German forces.