Weird. An important BBC story about racist use of Zyklon-B on Mexicans by the Americans… doesn’t seem to be reported in English anywhere. Crucial quote:

No hay que comparar peras con manzanas, pero el Holocausto no fue un hecho aislado y la frontera entre EE.UU. y México sirvió como un centro de experimentación importante de esas ideas.

Basic translation: while the racist act of America spraying Mexicans with cyanide is not the same as genocide by the Nazis, one apparently served as an example for the other.

Let’s go back to 1924 to begin this story, because that was when America invented a gas chamber specifically to kill people using cyanide.

Washington, Arizona, and Oregon in 1919-20 reinstated the death penalty. In 1924, the first execution by cyanide gas took place in Nevada… a special ‘gas chamber’ was hastily built.

In other words a gas chamber for death already had been established as an American thing by the time widespread application of cyanide (Zyklon-B) became a racist story about Mexicans.

It all came about in the 1920s after Woodrow Wilson infamously set the stage for industrialized/systemic discrimination with his “America First” platform of 1915 that restarted the KKK and removed non-white races from government.

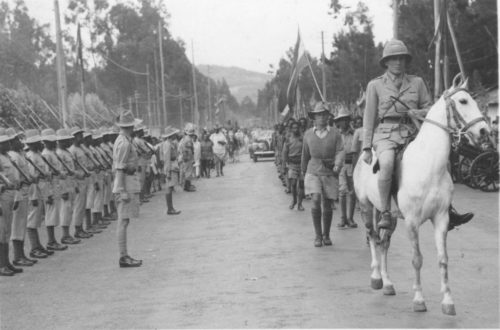

The documents show that beginning in the 1920s, U.S. officials at the Santa Fe Bridge deloused and sprayed the clothes of Mexicans crossing into the U.S. with Zyklon B. The fumigation was carried out in an area of the building that American officials called, ominously enough, “the gas chambers.”

To be clear here this was a federally funded system constructed using garbage theory (eugenics) and false pretense (Typhus was cited, even though not a risk) to poison and even burn to death people en masse, just based on race alone.

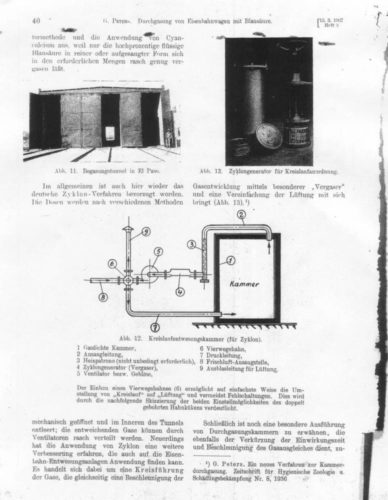

No wonder by the 1930s that Nazi Germany believed they could get away with doing the same things. A German scientific journal article was published in 1928, written by a Dr. Gerhard Peters that…

…specifically praised the El Paso method of fumigating Mexican immigrants with Zyklon B.

When you see the article, full of photos and drawings of American railroad cars pushing Mexicans into gas chambers, it’s hard not to think you are looking at images from Auschwitz two decades later.

Indeed, Dr. Peters then became the managing director of Degesch, one of two firms that mass-produced Zyklon-B for Nazi genocide.

At least 25 tons of Zyklon B were delivered to Auschwitz in the years 1942–1944. According to postwar testimony by Rudolf Höss, it took from five to seven kilograms…to murder fifteen hundred people.

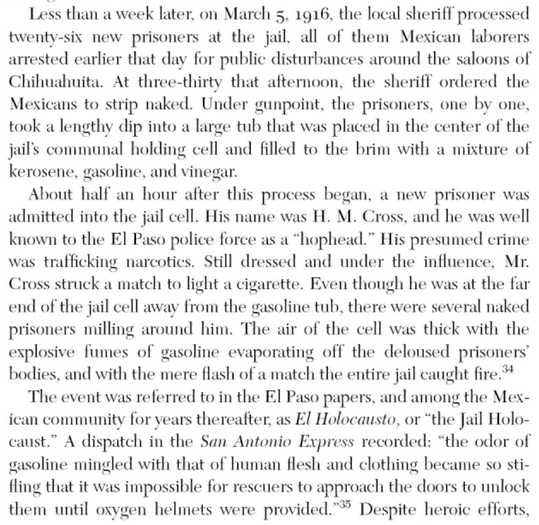

In case these clear connections to death chambers aren’t disturbing enough; Americans also held Mexicans at gunpoint and forced them to strip naked, then cover themselves in a highly flammable kerosene bath.

In retrospect it seems obvious a fire in a “holding cell” with closed doors would then burn everyone to death as if an oven. On March 5, 1916 such an event was literally reported in the papers as… wait for it… El Holocausto.

Dousing groups of Mexicans with kerosene and then burning them was also a topic of discussion for Americans on March 10, 1916 after the Battle of Columbus. Over 60 dead men were piled together, their bodies incinerated.

Keep in mind this all was in the context of Americans a year earlier calling for the “extermination” of non-whites, which led to killing thousands of Americans who were of Mexican descent:

While a mob’s stated reason [under Woodrow Wilson] for lynching black victims tended to be an accusation of sexual violence, for Mexicans in the United States, the reason given was often retaliation for murder or a crime against property: robbery, or what was sometimes called “banditry.” […] “The war of extermination will be carried on until every man known to have been involved with the uprising will have been wiped out.”

America was involved in a 1915 “war of extermination”, coupled with Zyklon-B gas chambers and even ovens burning groups of people in what was called a holocaust.

No wonder the BBC ran an article that reported plainly in Spanish…

México sirvió como un centro de experimentación importante de esas ideas.

Now, why can’t I find an English version of the story?

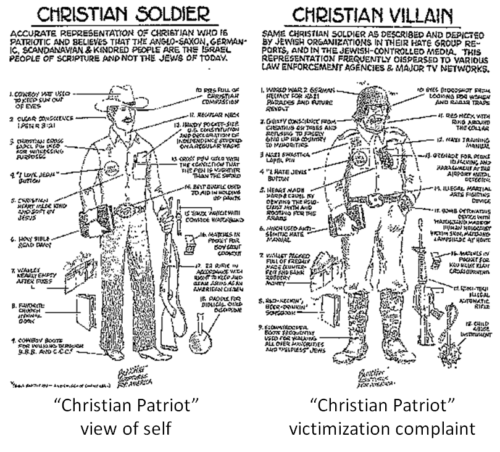

It reminds me of this old leaflet by extremist militant white insecurity groups in America informing their followers they can carry out atrocities of a Nazi (Villain) yet remain undetected simply by appearing like a Texas Ranger (Soldier).

Here’s a related video by Vox on the history of Carmelita Torres (the “Latina Rosa Parks“) who was murdered by American border officers in 1918 for protesting abuse by them:

For women there was also sexual humiliation. There were rumors that when they entered the plant and told to strip, officers were taking their photos and then posting them in bars.