Many moons ago you may remember this introduction to one of my car-hacking posts:

First, you need a Vehicle Identification Number (VIN). You can ask your friends or family for their VIN. You can walk into a parking lot, especially a Jeep dealer’s, and look at the VIN. Or you can search craigslist for a VIN. I used the SF bay area site but you can search anywhere using a simple URL modification…

The VIN is a token, a fairly important one, that requires manufacturers to use threat models to think about adversarial usage. Alas it sits in plain view both in person and online.

We interrupt this PSA about credential management to bring you a hot story about a brand new cutting edge technology Model 3 Tesla being stolen.

…a regular at the Trevls EV-only rent-a-car company in Minnesota was the key suspect in stealing a Model 3 rental car owned by the agency. According to the owner of Trevls, John Marino, the man simply walked up to the Model 3, opened it, got in, started it and drove off. Bloomington police are saying that “the man somehow manipulated the Tesla app to unlock and start the car, disabling the GPS before leaving town.”

The key here for the key suspect, puns intended, seems to be that this Tesla was rented before. The suspect had the VIN associated with his account and used the application, so was a temporary valid driver. A VIN has to be associated with an account to run the application, and I think most Tesla owners would not want any path for their public VINs to be “matched” to someone else’s account.

Alas, a rental company does exactly that, putting a VIN in random people’s accounts. The rental company claims they remove the VIN from a customer account after their rental, thus denying any further authorization. However, this driver likely realized since he was authenticated as a driver of that car at least once he probably could contact Tesla support and somehow convince them to add the VIN back to his account without authorization of the rental company. Or maybe the removal process wasn’t clean. Deprovisioning is notoriously hard in any credential system.

I’m going to go out on a limb here and say the Tesla application and driver support system wasn’t sufficiently threat modeled for the kind of VIN use that rental companies require, let alone social engineering talent of rental customers.

It reminds me once of sitting down with an automobile manufacturer and telling them while I enjoyed hacking cars I wasn’t about to start inserting USB into my rentals…and they interrupted me with a disgusted look on their face to say “WHY NOT?” I meekly explained I thought a lab was more appropriate as it would be dangerous for others to be renting cars I had been hacking on, especially when rental use wasn’t in the threat models (it wasn’t).

Police were scrambling for clues when this Tesla disappeared because, after the suspect reportedly disabled GPS, all the usual tracking signals (e.g. NFC/RFID scanning) on Interstate roads weren’t being helpful. The Tesla owner (rental company), on the other hand, noticed the stolen car being connected to the charging network and 1,000 miles from the scene of the crime (Minnesota to Texas in two days). Police simply went to the charging station and there they found the lazy thief, who despite noticing a loophole in authorization and means to disable GPS failed to think about other ways he could be charged.

And yes I wrote this entire thing just for the puns. You’re welcome.

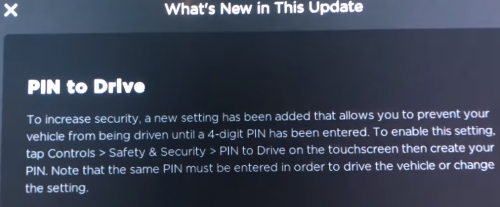

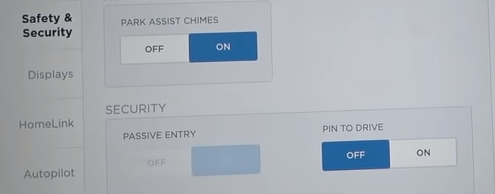

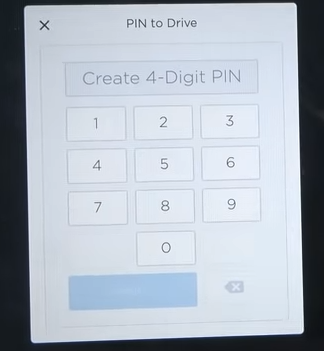

Update Sept 15: Telsa has pushed an update (2018.34.1) that offers a “PIN to drive” security option to limit use of a key.

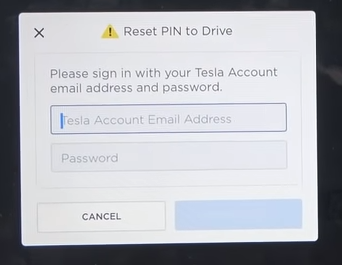

No word yet on the “forgot PIN, enter credentials to drive” flow resilience to social engineering. More to the point this update does not seem to leverage PIN to drive when using the mobile application with “keyless driving”…perhaps because if you can enter credentials for keyless driving you could start the car with the same credentials in the forgot PIN screen.