I told myself I wouldn’t treat this lightly and so it ended up being delayed a long while.

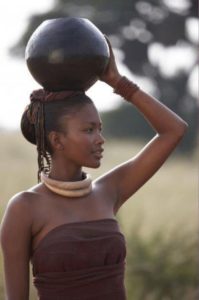

In a nutshell when a “water charity” would roll into villages in Africa they believed dropping a well directly outside homes would liberate women and children from the burden of long walks with heavy loads.

These wells in fact undermined a core network and fabric of social order and thus dangerously unbalanced power — women no longer had private time in shared chores away from the home at their “workplaces” and overall safety/security of the region was significantly undermined.

This is not conjecture. I was working with a huge global tech firm that was pushing a water charity donation pledge. When I started to question the ethics of the charity, the head of it came to meet with me in person.

At first it was cordial and he said things like “happy to answer your questions” though soon he seemed a bit frustrated, even deflated as if I had unmasked him. I had asked straight questions like “exactly how many villages had security issues after a well was dug”.

To his credit he told me could confirm exactly 15 examples (at that time). I appreciated the transparency, yet he seemed disturbed by having to admit to the fact an utterly simplistic solution (get donations, drive in, dig a well, leave) to a complex problem was in fact making lives worse.

In other words I was told by the head of a major charity that in more than a dozen cases soon after the new well was established armed rebels were known to target it, seize control and force all residents into refugee camps. That was fascinating, and still didn’t go deep enough for me as it focused on militant action more than the subtle process of cultural devaluation and collapse (e.g. Achebe’s “Things Fall Apart“). He admitted the lost villages were never reported, despite his transparency with me.

He also tried to muster some of the usual “big picture is we’re helping a lot of people” chaff. When I dug into his actual data (at that time) even it was questionable, suffering from big data integrity issues like obvious copy/paste numbers for a map of the wells scattered across an entire continent.

Finally, when I broached this subject with regional conflict experts they confirmed that the resource charity model was typically flawed from the start, and conditions worsened without analysis. They knew of the problems, and again said none of it was ever reported. More to the point, they confirmed they knew how introduction of wells (or similar technology shifts for that matter, such as men on bicycles fetching water) destroyed a traditional model of safety and power for women.

While perhaps counter-intuitive that reducing a burden creates far worse burdens, it lays bare the kind of false assumptions someone can make when they look at ways to “fix” networks and markets they observe only as “do good” outsiders.

If we think only about carrying water as hard we risk projecting that mindset into other communities and look for ways to remove that specific pain point. Instead we should think about how hard life becomes for people if they don’t have the opportunity to carry water on long isolated paths (removal of private time/place to communicate translates directly to loss of power).

The water charity seemed to be attempting what Fela had written about in the mid 1970s, in a song called “Water no get enemy“.

Initially, water was likely deemed the safest option for substantial and impactful donations. The idea was that nobody could oppose something as essential as water, and any critics would likely be perceived as misguided. However, there was a serious oversight in considering broader risk management related to resources.

To put it plainly, it seems the individual behind the water charity felt a sense of guilt for their past actions and attempted to portray themselves as a “white savior” by delivering water to black communities, thinking it would shield them from scrutiny. Unfortunately, addressing complex real-life issues is not that straightforward, and the search for superficially criticism-proof solutions only reinforces the self-dislike that led to this approach in the first place.

The failure to conduct a thorough threat analysis on water distribution had far-reaching consequences, disrupting security processes, procedures around assets and political power, and jeopardizing the privacy and safety of women and children. The belief in invulnerability was proved wrong.

Hubris proved even water could get an enemy.