The news is about some amazing efficiency in solving problems found by using a “protein folding game” called Foldit.

Researchers have for over a decade been unable to solve the structure despite using many different methods. Even recently, the protein-folding distributed computer program Rosetta@home that uses thousands of home computers’ idle time to compute protein structures, was not able to give an answer. The Foldit players using human intuition and three-dimensional pattern-matching skills, however, were able to solve the problem within days.

The scientific article published by Nature Structure & Molecular Biology (“Crystal structure of a monomeric retroviral protease solved by protein folding game players”) concludes with some amusing analysis by the scientists.

The critical role of Foldit players in the solution of the M-PMV PR structure shows the power of online games to channel human intuition and three-dimensional pattern-matching skills to solve challenging scientific problems. Although much attention has recently been given to the potential of crowdsourcing and game playing, this is the first instance that we are aware of in which online gamers solved a longstanding scientific problem. These results indicate the potential for integrating video games into the real-world scientific process: the ingenuity of game players is a formidable force that, if properly directed, can be used to solve a wide range of scientific problems.

This reminds me of both my high school chemistry and physics teachers who would always start lab work by saying something like “now, let’s make this fun”. So the first question I get from this story is why it has taken the scientific community so long to recognize the power of channeling human intuition through an interface that doesn’t suck.

I have my theories, of course. When I worked on systems used for digital imaging and communications in medicine (DICOM), and more specifically on radiology technology, I found an odd dilemma in the medical field — the most advanced interfaces were the least desired by highly-trained practitioners.

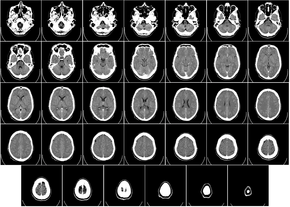

Medical researchers had me deploying new Irix workstations with high-end graphic processors to develop 3D fly-through capabilities of the human body. After a CT or an MRI scanner was done taking images in “slices” of the body these Unix systems would put all the images back together again into a virtual human. The researchers expected doctors to jump at the chance to use 3D.

To the untrained eye, let alone a gamer, the ability to fly through a patient’s body looked like a fantastic advance in medicine. However, when surgeons and radiologists sat down to look at the big screens (20 inches was big back then) they were unimpressed.

I’ll never forget one late evening when a surgeon rushed in for a pre-op debriefing. I was called in for support, and I stood behind him as he scrolled around the 3D body. Then he said “I can’t use this nonsense”, stood up, and walked over to a wall of old fluorescent-lit white boxes covered in greyscale film images of the brain. He scanned the wall, made some “mmm hmmm” sounds and left.

I stared at the wall of “slices” of the brain. There were literally hundreds of pictures that the surgeon had to put back together in his mind. It seemed like an impressive skill but it also made me wonder why the ability to put a 2D world into 3D would prevent the ability to see in 3D.

That’s a long way of getting to the point that the history of doing things a particular way in medicine creates ruts of reliability. It takes a long time, perhaps even years, for the industry to assess, approve and then adopt technology that a gamer might take less than 24 hours to try and like.

Anyway, this story reads to me like the scientific community has finally found a way to do what others have been doing for years — leveraging gamers to solve problems. And who better to solve 3D problems than people who are highly trained in 3D visualization? That being said I also noticed a slight dig against gamers in the phrase “ingenuity of game players is a formidable force that, if properly directed”.

Are we to believe that gamers are not a formidable force if undirected, or that their own direction is not as formidable as one led by scientists? Seems to me the scientists are the ones who were in need of direction.