The United States is gradually advancing its efforts in the field of expanding awareness about codebreakers and the origins of modern computing, akin to the remarkable work undertaken by historians at Bletchley Park in England. An article featured in DCist sheds light on significant revelations associated with “Building E on the Foreign Service Institute’s leafy Arlington campus”.

“The codebreakers who worked here saved countless American lives and shortened the war by what many historians estimate to be at least two years,” [institute director] Polaschik said.

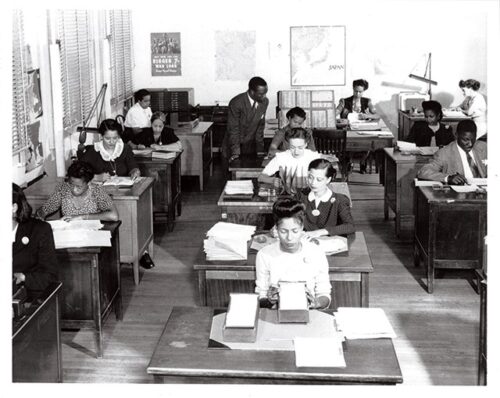

A group of Black women who worked at Arlington Hall — they were segregated from their white counterparts — kept tabs on messages from the private sector, ensuring that American companies were not doing business with Nazi Germany or Japanese companies.

Overall, women made up 70% of the American domestic codebreaking force, noted Adam Howard, the director of the Office of the Historian at the State Department.

[…]

At the end of the war, the women were mostly pushed out of their jobs to make way for men…

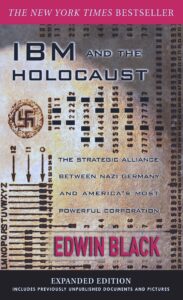

Listening to companies doing business with Nazi Germany? Like *cough, cough* Ford, IBM and Coke?

How awkward to enlist Black women to surveil the most powerful American brands for evidence of treason. I am sure it wasn’t hard for them to find America’s worst offenders, given evidence was so often out in the open while being ignored.

Furthermore, the conclusion of the Arlington story features a memorable quote that underscores potential injustices within America. However, it may not fully capture the nuanced and intricate web of challenges faced by women. A perfect example can be found in the case of Agnes Driscoll who expanded and thrived in intelligence work after her role in World War I ended, as documented in the NSA Hall of Honor.

In her thirty-year career, Mrs. Driscoll broke Japanese Navy manual codes — the Red Book Code in the 1920s, the Blue Book Code in 1930, and, in 1940, she made critical inroads into JN-25, the Japanese fleet’s operational code, which the U.S. Navy exploited after the attack on Pearl Harbor for the rest of the Pacific War. In early 1935, Mrs. Driscoll led the attack on the Japanese M-1 cipher machine (also known to the U.S. as the ORANGE machine), used to encrypt the messages of Japanese naval attaches around the world. At the same time, Agnes sponsored the introduction of early machine support for cryptanalysis against Japanese naval code systems. Early in World War II, Mrs. Driscoll was engaged in the U.S. Navy’s effort against the German naval Enigma machine, although this work was superceded by the U.S.-U.K. cryptologic exchanges in 1942-43. Mrs. Driscoll was part of the navy contingent that joined the new national cryptologic agencies, first the Armed Forces Security Agency in 1949 and then the National Security Agency in 1952.

Driscoll’s postwar career experienced a remarkable ascent, rather than being obstructed by male colleagues. It’s intriguing to observe that the greater a woman’s success in the field of cryptology, the less recognition she tends to receive especially if Black. This phenomenon could be attributed to a paradox: the less they are forced out, the more they are drawn into the shadows, if that conceptually aligns.

One might ponder whether any Black woman listening to the overtly racist white men driving American private sector to support Hitler and genocide (let alone the racists around them at work) would truly desire corporations like Ford, IBM, and Coca-Cola (among others) to unveil the extent of knowledge she possessed.

Here’s a medal. Now you’re dead.

On that note, the NSA claiming “work was superceded by the U.S.- U.K. cryptologic exchanges in 1942-43” completely obscures the critical role of Polish codebreakers. I wonder how this keeps happening to extremely important yet humble men in history like Rejewski.

It’s necessary for individuals, regardless of gender, to practice self-limiting humility when discussing their role in intelligence. Seeking attention and recognition for such roles is generally considered inappropriate, and yet we see men far earlier and more often breaking the most basic rule about breaking rules (e.g. spying often is by definition illegal). It’s not about encouraging women to become boastful too, and rather about protecting the necessary culture where both men and women are expected to refrain from stealing the limelight and instead focus on collective morally justified achievements of the team.

For example, a man received a recognition for supervising Black women at Arlington, while all of them apparently remained unknown and unrecognized.

Whereas stories of their white counterparts have come to light as records have been declassified, the identities of most of Arlington’s Black code breakers remain unknown.

In researching her book, Mundy scoured National Security Agency records, among many other sources, and uncovered only two names of Arlington’s Black women code breakers: Annie Briggs, who headed up the production unit, which worked to identify and decipher codes; and Ethel Just, who led a team of translators.

William Coffee, a Black man, supervised the women and recruited many of them, later winning an award for his wartime leadership.

The percentage of women to men in that photo is typical of codebreakers, if you ask the NSA historians. So let me also make an important point about the book-writing and touring reference in the above article quote:

Mundy scoured National Security Agency records…and uncovered only two names of Arlington’s Black women code breakers

Twenty years before Mundy the NSA Center for Cryptologic History published a book in 2001 called “The Invisible Cryptologists: African-Americans, WWII to 1956″ by Jeannette Williams with Yolande Dickerson (researcher).

In early 1996, the History Center received as a donation a book of rather monotonous photographs of civilian employees at one of NSA’s predecessors receiving citations for important contributions. Out of several hundred photographs, only two included African-Americans – an employee receiving an award from Colonel Preston Corderman (reproduced on page 14) and the same employee posing with his family. […] the war came, and we needed to expand. They bought Arlington Hall, and built two buildings – A Building and B Building – and we moved on Thanksgiving Day of ‘42. I’m not sure when the first blacks came, but Geneva Arthur was one of the early ones [in 1947].

Geneva Arthur.

Just saying, Mundy allegedly “scoured” NSA records and then left out Geneva Arthur in the machine section, a Black woman who rose all the way to being section head before retiring in 1973 as documented in 2001 by the NSA. Annie Briggs and Ethel Just also were mentioned in the same book by the NSA.

I suppose the real question here is whether, like Driscoll, Black women in intelligence became so accomplished they were promoted quietly and intentionally restricted by race into being further buried in secrecy — deciphering Soviet communications on the Venona project based on Genevieve Grotjan’s celebrated work. Yet very unlike the celebrated Grotjan the very many other names have been completely written out of history.

We really have to put this in proper perspective, because it used to be a given that computers meant women and then essential career-motivating factors (e.g. taking care of others, doing the right things, optimism and hope that things were going to get better) were used against them.

In June 1942, when the US government took over Arlington Hall under the War Powers Act to become their center for military intelligence and cryptanalysis, it was an all-female Junior College and boarding school.

A year later something like 2,500 civilians and 800 military staff had been assigned to the station. To put it another way, women codebreakers initially were signed on as lesser civilians, as men directly entered above them into the benefits, recognition and status of being military.

[Eunice Russell Willson Rice] joined the Office of Naval Intelligence as a language analyst in 1935 and transferred to OP-20-G—the Office of Naval Communication’s Code and Cipher Section—as a civilian cryptanalyst in 1939. During WWII, Rice led the team working Italian ciphers and codes, then learned enough Japanese on her own to lead the team charged with recovery and analysis of the vital Japanese Water Transport code.

The monotony of repetitive precision work with letters and numbers (likened to crossword puzzles), let alone huge patterns of tiny thread-like wires, was treated as women’s work and famously called computing. In all aspects of software and hardware, therefore, computers in America initially were being quietly developed and operated predominantly by women as credit flowed into the hands of men around them.

Ms. Blum was one of the pioneers in writing computer software at NSA. She led the effort to recruit Agency employees to learn how to program cryptanalytic techniques. She was aware of and taking advantage of the computer language FORTRAN at least three years before it became publicly available in 1957.

Official American history tells us that IBM released the first commercially available computer language “Formula Translation” (FORTRAN), giving credit to John Backus. Is that right? Probably not.

The NSA tells us instead half-a-century later that Dottie Blum was given a special role at IBM and was developing FORTRAN by 1954. Dottie had for years worked on U.S. Army BOMBE hardware for decoding Enigma, before she worked on the 1950 Standards Easter Automatic Computer (SEAC). Therefore her seasoned influence into FORTRAN is likely much larger than ever stated, just like her mostly unknown colleague Henriette Avram (who also wrote programs for the IBM 701) much later was credited only with developing MARC.

These are the giants of history we know a little about, leaving the large question of what the ghosted Black women of Arlington Hall accomplished that made their secrecy so important. Were they just trying to stay alive by never revealing what they knew about notoriously racist American private sector corporations who had backed Hitler, or trying to fit into a work environment that did little to prohibit or end racism?

According to [chief of the Russian plaintext exploitation branch in 1948] Jack Gurin, the critical need for clerical support prompted him to approach the personnel officer with a request for additional typists. He was told that “Code 1’s” were not available, but “Code 2’s” could be obtained. The coding, it was explained, was used on personnel records to designate race. “Code 1” was white; “Code 2” was “colored.” On the advice of the personnel officer, Gurin discussed with the existing branch personnel the possibility of bringing “Negroes” into the unit. One person, “a very dignified, good-looking Alabama lady, objected, stating that she could not ‘sit next to a colored person and work’.” Gurin relocated her desk…

Jack Gurin, anti-racist agent of change, stands as a good example of white men we should also hear more about.

But what were the names of all the Black women and what credit are they missing? The NSA notoriously built a reputation of hiring single young white women from the American south. I mean Black women apparently were instrumental in monitoring private sector companies during WWII yet afterwards we hear only about white women tasked and trusted with big IBM research roles…

I came to be interviewed at Arlington Hall in 1951, and there was a woman. I don’t know her name, but she was white… she vowed that I would not be ‘going down in the hole’… Most of the blacks at that time were assigned to the basement.

Fascinating post! I believe my mother might have been one of the Black code breakers at Arlington Hall Station. The only thing she ever said about what she did in WWII was that she was a “teletype operator”. But she spoke 4 languages fluently (Spanish, French, Italian and, of course, English), spoke some German, graduated from Howard University in 1941 and would have known Ethel Just, a language professor at Howard and later head of the translating unit at Arlington Hall Station. My mother is deceased now but I do wonder…