After liberating American troops firebombed the Nazis out of power in Berlin, Germany’s Bundestag reconstruction was very carefully curated in a serene color of profound philosophical heritage — one that traces the relationship between color and governance through centuries of Western thought. The lineage of blue was known for a political intention in rational deliberation, whereas bold reds marked a palette of mass death through extremist violence and hate groups.

“Reichstag blue is a well-chosen color. It can create a calm atmosphere in the Bundestag,” color expert Silvia Prehn told DW. “It is a calm color that conveys clarity and objectivity. Blue has a physically calming effect — one’s pulse and breath slow down as it relaxes and soothes.” […] The new foreign minister, Annalena Baerbock, would be more likely to be the heir to the “German Blue”: “Just yesterday she wore exactly the same color as the chairs in the Reichstag, that is, aquamarine with a bit of purple,” says the color expert. “She wants to be taken seriously.” Whether top German politicians in the new government take up the blue again or not, the chairs in the Bundestag will continue to be “Reichstag Blue.” “The blue stands for the thinkers, analysts, the people with the data, numbers and facts,” says Prehn. “Violet, on the other hand, represents the visionary and the foresighted.”

Though this relationship proves more complex across cultural contexts, the following analysis draws out patterns and meaning for national security discussion purposes rather than apologetically back away from useful predictors of threats.

The red brick thrown to destroy structural beams

Could instead shelter a children’s dreams.

The connection between blue and representative reasoned governance has roots in Western classical philosophy. Plato, in “The Republic,” speaks of a philosopher-king’s need for contemplation, where he associated vast blue depths (e.g. the sky, the ocean) with divine wisdom. While color theory wasn’t explicit in his writing, emphasis on forms of rational governance over fiery emotional appeals laid some groundwork for later analysis.

Immanuel Kant’s “Critique of Judgment” (1790) developed a crucial color theory relationship to governance. Whereas Kant held color secondary to form, he provided an analysis of “cool” versus “warm” experiences in aesthetics. This has influenced how later theorists understood color’s active role for intentionally shaping human behavior and defining the outcomes from our spaces.

The elevation of blue in Western governance cannot be separated from its religious significance. The use of “Marian Blue” in Christian iconography, particularly expensive lapis lazuli pigments, associated the color with divine wisdom and contemplation, as Michel Pastoureau documents in “Blue: The History of a Color” (2001). Richard H. Wilkinson in “Symbolism & Magic in Egyptian Art” (1994) informs us how rituals since ancient times have used red to represent danger and death, while blue was for birth and sustainable life. Islamic architectural traditions similarly made extensive use of blue tiles in places of worship and governance, as detailed in Robert Hillenbrand’s “Islamic Architecture: Form, Function and Meaning” (1994). The Great Blue Mosque in Istanbul shows blue applied to represent expressions of divine wisdom and earthly authority. Meanwhile, Buddhist and Hindu traditions have used red to suggest a shedding of the past in transition to revolutionary insights, as David Fontana suggests in “The Secret Language of Symbols” (1994).

Both religious symbolism and secular governance aesthetics, despite the vast differences in other regards, apparently arrived at a universal recognition of color meaning. The Soviet and Chinese communist movements, for example, dramatically made use of red’s symbolism and rejected blue. Both flags deliberately combined red with yellow/gold stars, a combination that Michel Pastoureau identifies in “Red: The History of a Color” (2017) as historically associated with imperial power. The British “red coats” had such an influence over American colonies that to this day the more “militant” minded adorn themselves with “salmon” shirts and “pink” pants to express soft-skin hard-head conservatism. Their palette signifies underlying politics of harsh exclusion and white-washing race-based privilege.

The Swiss flag’s red, originating in the 13th century Holy Roman Empire, presents an especially revealing case study in how militant symbolism evolved into a facade of “neutrality” that enabled profound moral failure. While Switzerland inverted its red cross on white background to create the Red Cross symbol in 1863, supposedly representing humanitarian neutrality, this same “neutrality” would later serve as cover for Swiss complicity with Nazi Germany. During WWII, Swiss banks laundered Nazi gold, refused Jewish refugees at their borders, and maintained profitable trade relationships with the Third Reich while claiming moral distance through their red-branded neutrality. This transformation of militant red into “neutral” red ultimately served the same authoritarian ends through passive facilitation of genocide for profit rather than active revolution.

The history of red in governance thus presents fascinating insights beyond mere revolution. The American flag incorporated red from Britain and France, marking a sharp contrast with its application of blue for justice and vigilance. The founders of America observed the color red in French political conflicts, which carried particularly profound revolutionary, symbolic, and political meanings.

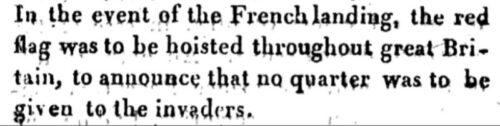

During the 1789 French Revolution, red was prominently associated with abrupt course change through bloodshed. It was incorporated into the National Guard’s cockades for a unifying symbol of Parisian revolutionaries, later appropriated into the French tricolor, where it represented the fight to end prior rule. Napoleon Bonaparte thus cynically marked his seizure of power with red, pressing the color further into a French symbol of abrupt grab of authority. His uniforms and depictions often featured red elements to express dominance and imperial violence. Under his rule, France transitioned rapidly from popular revolution to unjust dictatorship, showing how red’s use to foment widespread rebellion has been rooted in tragic centralization and control. A historian remarked in 1825 how the British planned to hoist a red “no quarter” flag upon invasion by France, in order to warn only mass death lay ahead.

Later revolutions, such as those of 1830 and 1848, reaffirmed red as the emblem of rabid disruption and rejection of any compromise or concession in governance.

This is all important context for why Berlin’s “Reichstag Blue” represents a deliberate application of philosophical principles. When redesigning the Bundestag after reunification, architect Norman Foster collaborated with color psychologist Professor Max Lüscher, whose “The Lüscher Color Test” (1969) demonstrated blue’s calming, thought-promoting properties.

Michel Foucault’s “Discipline and Punish” (1975) suggests our institutional spaces and symbols measurably shape behavior, arguing that environmental designs — including color — promote either rational discourse or emotional manipulation.

Many other contemporary international organizations thus have largely embraced blue as a symbol of rationality and peace. The United Nations’ light blue represents peacekeeping missions, while the European Union’s blue flag with gold stars symbolizes unity and reason. NATO’s blue emblem similarly suggests stability and collective security rather than aggression.

The Republican Party’s adoption of red in 2000 during electoral coverage, however, marked a subtle but significant regression to authoritarian aspirations. What began as supposedly arbitrary choice revealed deeper intentions with the racist and anti-democratic MAGA movement’s gleeful promotion of bright red merchandise for overthrow of government. The color choice, whether broadly intentional or isolated, aligns with historical patterns of authoritarian movements. Color theorist Johannes Itten termed this use of red for maximum contrast in “The Art of Color” (1961) as an intentional technique to provoke emotional rather than rational responses — bold, high-contrast colors used to disrupt or blockade rational discourse by triggering emotions instead. Contemporary theorist Eva Heller notes in “Psicología del color” (2000) that while blue promotes “intellectual understanding and diplomatic communication,” red triggers “fight-or-flight responses” and emotional arousal useful for rapid power grabs.

Similarly the German party of Nazis today (“Alternative for Germany” or AfD) continues to use red very tactically in their propaganda filled hate campaigns.

The logo “Alternative for Germany” is visualized as a flashy red arrow resembling the commercial Nike logo. The color red acts as a signaling function and recalls the visual style of electoral propaganda campaigns by other far-right parties (Kress and Van Leeuwen 2006; Doerr 2017a).

The known contrast between careful contemplative blue versus the emotional reactionary red in political movements reveals a fundamental pattern in human governance.

Whether deployed as the bright red of revolution, the calculated red of imperialism, or the sanitized red of profitable “neutrality,” this particular color consistently served to either provoke or enable authoritarian impulses. As we witness the rise of populist movements worldwide, especially the return of nativist xenophobic groups such as MAGA, the conscious color choices in governmental spaces and symbols serve as crucial indicators.

The Bundestag’s blue chairs stand as the architectural commitment to reasoned debate, backed by centuries of philosophical and psychological understanding. The persistent use of red by authoritarian movements — from the Nazis to their Swiss enablers to modern extremists — demonstrates how color serves as both a tool and warning sign in the human evolution towards thoughtful rational governance away from rushed extreme emotional manipulation.

Red revolutionary violence (French, Soviet, Chinese)

- French Revolution (1789-1799)

- Reign of Terror executions: ~17,000

- Vendée massacre: ~170,000

- Total French Revolution deaths: ~500,000-600,000

- Soviet Red Terror (1917-1953)

- Great Purge executions (1934-1939): ~1.5 million

- Induced famine (1932-1933): ~3.9 million

- Gulag system deaths: ~1.6 million documented

- Total Stalin-era deaths: 20-25 million estimated

- Chinese Communist Revolution (1949-1976)

- Great Leap Forward deaths (1958-1962): 15-55 million

- Cultural Revolution killings (1966-1976): 1.5-2 million

- Total Mao-era deaths: 40-80 million estimated

Red imperial power (British Empire)

- Atlantic slave trade (1500s-1800s): ~3.5 million deaths during transport

- Indian famines under British rule (1769-1943):

- Bengal Famine (1769-1773): ~10 million

- Great Famine (1876-1878): ~5.5 million

- Bengal Famine (1943): ~3 million

- Irish Potato Famine (1845-1852): ~1 million deaths

- Total estimated deaths under British Empire rule: 35-40 million

Red Nazism and false neutrality (German, Austrian, Swiss)

- Holocaust Jewish victims: ~6 million

- Total concentration camp deaths: ~11 million

- Swiss border rejections of Jewish refugees: ~24,500

- Total World War II deaths: 70-85 million

Red privilege and racist authoritarianism (New England Reds, Red Shirts, Red Summer… MAGA)

- Colonial slave trade participation (1670s-1800s)

- Connecticut ports trafficked ~12,000 enslaved people directly

- New England merchants deeply embedded in triangle trade

- Yale, Brown, and other universities built with slavery profits

- Maritime trade routes connected to Caribbean plantations

- Prestigious New England families’ fortunes tied to slave trade

- Indigenous displacement (1630s-1770s)

- 90% population decline of native peoples

- Pequot War massacres and enslavement (1636-1638)

- King Philip’s War devastation (1675-1678)

- Systematic land seizures through “legal” mechanisms

- Cultural destruction via forced assimilation

- Disease and starvation from destroyed food systems

- Industrial militarization (1800s-present)

- Major arms manufacturers established:

- Colt (Hartford, CT)

- Winchester (New Haven, CT)

- Smith & Wesson (Springfield, MA)

- Weapons supplied to:

- Both sides of Civil War

- American westward expansion

- International conflicts

- Domestic civilian market

- Created massive wealth while enabling violence

- Established political influence through arms manufacturing

- Modern defense contractors continue this legacy

- Major arms manufacturers established:

Related: MAGA narratives such as “Waving the Red” in large crowds to symbolize “going back” have a specific American history.

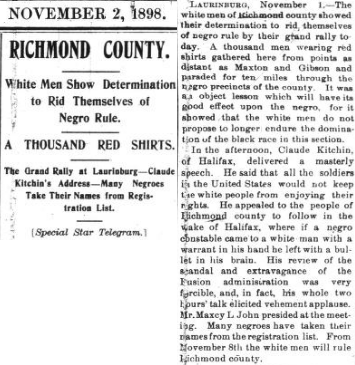

- The Red Shirt Movement in North Carolina 1898-1900, Prather, H.Leon, Journal of Negro History 62.2 (1977): 174-184.

- Riots in North Carolina: Red Shirts Drive Off Populist Speakers and Destroy Stand, New York Times, 2 August 1900.

- White Men Show Their Determination to Rid themselves of Negro Rule: A thousand Red Shirts, Morning Star, 2 November 1898.

It is a calculated mockery of horrible and deadly tragedy as MAGA-reds loudly signal where and when they want to “go back”…

Red Shirts were often worn by local chapters of what were socially known as “rifle clubs” but were in fact paramilitary groups across the South who worked to intimidate local freedmen and White sympathizers. Red Shirts often gathered at political rallies for candidates like Wade Hampton, or stood at polling places during elections, using intimidation and the threat of violence to prevent local Black residents from voting.

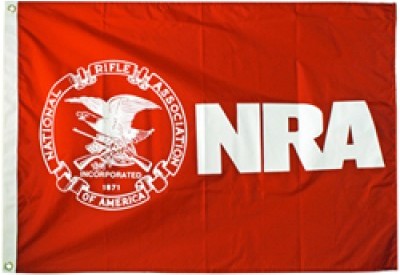

Surely you know this American national “rifle club” reference? Think about who was commandeered into running American guns into 1980s South Africa to prop up apartheid, and then setup domestic chapters to intimidate voters. Perhaps you’ve even seen their merchandise?

Really enjoyed reading this! It’s fascinating to see how political symbols evolve over time, especially how color choices like red took on such deep meanings in American history (and Canadian, eh). The way you explain the shift in the political landscape is thought-provoking. Looking forward to more insightful pieces like this. Keep up the great work!