The New Yorker employs people whose job is to ensure that claims can be substantiated before publication. In November, its parent company fired one of them for “extreme misconduct” that it refuses to describe, claiming there is footage it refuses to release, during an incident where he reportedly said nothing.

Jasper Lo learned he’d been terminated while attending a retirement party for the head of the magazine’s copy department.

He’d spent his career in the verification trade.

Now he’d been eliminated by assertion alone.

When the Fact-Checker Is Forced Into Silence?

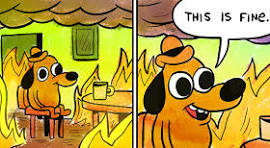

This is not, in the end, a story about labor relations at a magazine company. It is a story about what happens when institutions that profit from accountability eliminate that accountability from their own operations, and what that elimination tells us about the hollowing of American institutional life.

The Unverifiable Institution

Condé Nast’s official position is that four employees, including Lo, committed acts so severe they warranted immediate termination. The company deployed the language of emergency: “aggressive, disruptive, and threatening behavior,” “targeted harassment,” “extreme misconduct.”

The available evidence shows union members asking questions in a hallway.

Two video clips, obtained by The Washington Post, document the November 5th encounter. About a dozen employees from various Condé Nast publications gathered outside the office of HR chief Stan Duncan to ask about the shuttering of Teen Vogue’s website. Duncan declined to engage. An employee followed him down the corridor, asking if he was “running away” from answering questions.

Someone booed when his door closed.

A boo. That’s the documented record.

The company says there’s more footage. The company won’t provide it. Spokesperson Danielle Carrig asserts that “most people recognize that the misconduct exhibited by union members wouldn’t be acceptable in any workplace.”

She invites recognition while refusing a show.

Lo’s union co-chair, Daniel Gross, called it “frankly embarrassing that executives would make baseless claims about a fact-checker.” But embarrassment requires shame, and shame requires an audience capable of imposing consequences.

Condé Nast has correctly identified that no such audience exists.

The Pattern

These “march on the boss” actions, the union notes, have occurred repeatedly in recent years. Management complained. No one was disciplined. Then, suddenly, four people were fired within hours of a hallway conversation.

What changed wasn’t the behavior. What changed was the decision to characterize routine union activity as termination-worthy misconduct—and to do so in language borrowed from physical threat without documenting any physical threat.

This is how institutional power operates in late-stage American capitalism: the rules remain constant while enforcement becomes arbitrary, allowing management to select which violations matter based on which violators they’d like to eliminate. The letter of the policy becomes a weapon retrieved from storage when convenient.

The four terminated employees now carry public accusations of “aggressive” and “threatening” conduct. Condé Nast faces no obligation to prove these characterizations in any forum with evidence standards. The NLRB grievance process means the dispute gets resolved through negotiation or private arbitration. The company can maintain its narrative indefinitely without substantiation.

The process is the punishment.

By the time arbitration concludes—if it concludes—the message will have been received by every remaining employee: questions have consequences; questioners are disposable; documentation is optional for those who control the documentation.

The Independence Question

Deputy poetry editor Hannah Aizenman located the structural problem in an internal email: New Yorker leadership either endorsed this firing or couldn’t prevent it.

I’m not sure which is more disturbing.

Both options answer the same question.

The New Yorker has operated for a century on the premise that editorial independence justifies its institutional existence. Readers pay premium prices for the assurance that the magazine’s journalism isn’t subordinate to corporate interests.

Editor David Remnick, through a spokesperson, declined to comment.

His silence is definitional.

When your fact-checker gets terminated based on unspecified allegations, editorial independence means you either defend him publicly or acknowledge you lack the authority to do so. There is no third option that preserves the independence claim.

Remnick’s non-comment is itself the comment: whatever power he holds, it doesn’t extend to protecting his own verification staff from HR.

The magazine released a Netflix documentary on December 5th, “The New Yorker at 100,” celebrating its legacy of integrity and rigorous journalism. The timing is, as they say, unfortunate.

What Remains

New York Attorney General Letitia James appeared at a rally for the fired workers and announced she wasn’t “afraid to march into a courtroom.” There is no courtroom. The process is arbitration. The statement was for cameras, not consequences.

This is the American pattern now: the symbols of accountability persist while the mechanisms dissolve. Officials make strong statements. Institutions issue values declarations. Documentaries celebrate legacy. Meanwhile, a fact-checker gets fired for something no one will specify, the company that fired him sells subscriptions on the promise of verification, and the only tribunal with jurisdiction meets in private.

The New Yorker built its reputation as the publication that checks. It employs people who call sources, confirm quotes, verify claims. Its fact-checking department is famous—the subject of books, the model for an industry.

That department just lost a senior member to unverified assertions from management.

The magazine will survive this. Condé Nast will continue publishing. The documentary will stream. Subscribers will renew. The question is what the institution becomes now and what its transformation tells us, about the trajectory of an America that once traded on credibility.

The answer is in the silence, again.

The fact-checker didn’t speak during the confrontation, and now the editor won’t speak about the firing, and the company won’t speak to what actually happened, and the resolution will occur where no one can hear it.

This is how accountability culture ends. Not eliminated, but privatized. Not abandoned, but applied selectively. Not discredited, but revealed as another luxury product—available to subscribers, unavailable to employees.

The New Yorker at 100: still checking facts, except the ones that would embarrass power. The magazine’s own conduct is not, apparently, within the scope of its legendary rigor.

Some things remain above verification.