Malcolm Gladwell hosts a history podcast that looks into wargaming to find the “best way to prepare for the unexpected”.

Spoiler alert: “Russia always won”.

Malcolm Gladwell hosts a history podcast that looks into wargaming to find the “best way to prepare for the unexpected”.

Spoiler alert: “Russia always won”.

I’m not convinced yet that there was a good way for the US to exit Afghanistan. Part of saying that the exit has been a disaster is to project or predict some better way to go about it.

Historians of the future will undoubtedly debate whether any good exit existed at all, and I for one am not seeing any evidence of it yet.

Think of it like a car accident. In the first two minutes as lanes are merging, many options in a decision tree present themselves with several good outcomes. Yet in the last seconds before slamming into each other, it’s just a matter of stop loss.

The only options left are all bad ones. This isn’t to say better options didn’t exist earlier, just that the point at which sudden and abrupt movements had to be made they all look bad.

With that in mind, after reading the story of US Army Special Forces officer Jim Gant I’m pretty sure he was exactly right about how to win the war. And not for the most obvious reasons. This makes perfect sense to me, for example:

…decentralized effort focused on empowering Afghanistan’s tribes rather than one that bolstered a corrupt central government…

That’s tapping right into the core of transitions we’re seeing around the world. Gant was on to something much, much bigger than Afghanistan.

It’s a narrative we even see played out regularly in the American news of its domestic tribes pushing for more “freedom” (read as control) and less oversight.

Just to be clear, flying the Confederate battle flag is tribalism. A group calling itself “Proud Boys” is tribalism. Perhaps it then has to be said that in no way would empowering these tribes in America turn out well for America.

And there’s the rub. Which tribes get to be magically empowered through foreign military intervention and why? Who decides and how? This was some of the (admittedly very naive and weak) foundation of my masters thesis work decades ago.

What jumped out at me in Gant’s particular study of the problem was something completely unexpected. (Full report in PDF: “One Tribe at a Time – A Strategy for Success in Afghanistan“)

Let’s go back in history for a minute.

In the 1800s President Grant required that his wife be buried along side him, and in doing so he was refused his rightful place in a US military cemetery.

The best general and best president in American history was literally denied proper burial rights only because he cared so deeply for his life partner.

That is why Grant’s massively impressive tomb instead is conspicuously in the heart of NYC.

Gant’s story had a interestingly similar tone, since the woman he married joined him in the field. He brought her close enough that the US military wanted Gant out. Somehow that seems like a giant clue, Gant might have been so far ahead, really understood victory in a way Grant did too, that his ideas seemed so good and deserve much more attention.

He perhaps could have even won the war.

The bureaucratic hurdles he was up against were his downfall.

Douglas Lute, “a three-star Army general who served as the White House’s Afghan war czar” under former Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, told interviewers “we were devoid of a fundamental understanding of Afghanistan – we didn’t know what we were doing.”

“What are we trying to do here? We didn’t have the foggiest notion of what we were undertaking,” Lute said in 2015, according to the Post.

In another example, Jeffrey Eggers, a retired Navy SEAL and White House staffer for Bush and Obama, bemoaned the cost of the war to interviewers, asking, “What did we get for this $1 trillion effort? Was it worth $1 trillion?” the Post said.

There’s a big disconnect between spend and value here, especially when you look at the transition from authorizing “harass” tactic under Carter, to full-bore support of extremist right-wing religious militants under Reagan and Bush.

But is the right answer to shut off spending or to increase value from that spend? Are either options realistic?

It brings to mind retrospectives on an unsustainable cost of the Vietnam War, such as this one:

When you stop to think about it if you have $30M orbiting reconnaissance aircraft to transmit signals, and $20M command post to call in four $10M fighters to assault a convoy of five $5000 trucks with $2000 worth of rice, it’s easy to see that’s not cost-effective. This is a self-inflicted wound… a losing proposition…

That’s only a little bit ironic given Brzezinski in 1980 wanted the US to get into Afghanistan to make it into a Vietnam War for the USSR; a form of payback that would create political quagmire too expensive for the Soviets to sustain militarily.

Saying in 1980 that Kabul should be the Saigon of the USSR has literally turned into Russia saying Kabul should be a repeat of Saigon for America; don’t forget Putin cut his teeth in the KGB during the 1980s.

However, despite all these interesting and useful references to Vietnam, Gant’s predicament reminds me much more of the American Civil War.

I’m especially thinking about Lincoln’s decision to expeditiously promote Grant right to the very top of decisions.

When I read it was a West Point graduate who petitioned to have Gant removed from his post — a hint at patronage instead of competence as a deciding factor — it reminded me of Grant as well. Grant had success navigating West Point while refusing to play into its patronage system, such that if America had depended on the men above Grant to win the Civil War it’s not clear they could have done it without him.

In that context, although I have limited Gant background, we have to wonder what would have happened if Gant had been promoted for his ideas and skill instead of kicked out on some technicality.

First of all I just want to say I think a new article in The Hill is excellent.

It makes a lot of great points using sound analysis explaining how the Pentagon lost Afghanistan, such as this paragraph.

The U.S. military still lacks a comprehensive field manual and “doctrine” on how to achieve wholesale security force assistance, even though it has been core to our exit strategies in Iraq and Afghanistan for years. Why? Because our military’s identity is about assault and not occupation, and training foreign troops smells of occupation. We would rather blow up the enemy.

Second I want to say the American “occupation” of itself after Civil War could become the canonical example of why American forces have had difficulty identifying with the critical phase that comes after blowing up the enemy.

Look at the 1865 Mississippi concentration camp controversy for a fascinating and detailed case of post-war refugee crisis handling.

Consider that the American military track-record includes confronting the long history of Confederate South attempts to shame or obscure America’s most successful military leaders at nation-building as well as occupation.

Anyone who wants to speak about the American military identity being forged and focused on assault, rather than suited to an occupation, should thus consider how the 1870s and rise of lynchings and Jim Crow might be proper framing.

We could benefit from more history analysis like the following paragraph in another expert op-ed on the war in Afghanistan (which highlights just how an “occupation” phase goes missing from the American narrative):

Though the Federal Army fought the Confederate Army, both armies were composed of locally raised forces like Joshua Chamberlain’s famed 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment that was made famous for defeating the 15th Alabama Infantry Regiment at Gettysburg. Such forces fought bloody battles across America that eventually led to the standing army we have today with no such regional affiliations. But that took decades.

That’s a good telling of the assault phase, yet not exactly accurate overall. We obviously know that the standing army 150 years later still had to explicitly ban soldiers from flying the “regional affiliation” battle flag of the Confederate South. Ouch.

Third, I feel I have to point this history out because The Hill article makes an unbelievably bad error in analysis — an unforced error, a cardinal and common error in American thinking that helps highlight exactly why “our military” is so bad at occupation doctrine.

The following paragraph in The Hill is like nails on the chalkboard to me.

…conduct human-rights vetting of all candidates for the security forces, which is not just a good idea but also U.S. law (22 U.S. Code § 2378d). We would never dream of putting cops on our streets or soldiers in our military without a background check, but it’s what we did every day in Iraq and Afghanistan.

No no no no.

The history of America tell us the exact opposite. After losing the Civil War the Confederate South soldiers who had sworn to destroy America were appointed to run police… and predictably started to massacre Americans.

…summer of 1865, just after the Civil War, Union commanders in the battered port city of Wilmington, N.C., appointed a former Confederate general as police chief and former Confederate soldiers as policemen. The all-white force immediately set upon newly freed Black people. Men, women and children were beaten, clubbed and whipped indiscriminately… One of the most terrifying examples erupted more than a century ago, when white supremacist soldiers and police helped hunt down and kill at least 60 Black men in Wilmington in 1898.

This is a serious national problem, as I’ve written here before several times.

…Camp Pendleton in Oceanside, California was a hotbed of KKK activity–an open secret that was tolerated or aided by Marine Corps brass… white marine Klansmen openly distributed racist literature on the base, pasted KKK stickers on barracks doors and hid illicit weapons in their quarters…

Such “background check” failures in human-rights vetting continue to this day. Here is some 2020 news!

FBI agent has documented links between serving officers and racist militant activities in more than a dozen states.

I’ve also pointed this kind of error out before with regard to Delta Force Commander memoirs — how basic ignorance about culture and history (e.g. thinking there’s no American equivalent to Afghan “night letters“) creeps into even the most elite American military narratives despite best attempts at being widely studied and not ignorant.

Missing these obvious parallels to American history and ongoing practices can be a form of cognitive blindness and its explanations are not pretty.

The Hill gets so much of the analysis right, yet it throws a giant wrench right in the middle of itself begging a question of how did they make such a giant error.

Basically American security experts regularly overlook domestic terrorism and corruption, or pretend it doesn’t exist, when it involves white insecurity groups that target people other than themselves.

I’m sure it’s a sobering thought to some, while for others in America it’s very well known.

Anyone who experiences or studies the very harsh side of cops on American streets and soldiers in American military, those studying the consequences of weak background checks, knows the “every day” failures in Iraq and Afghanistan could easily be argued to have roots… in sordid American history of human rights abuses.

Fourth, and probably superfluous to this post, is that my degrees are in this exact topic of occupation, or more formally the ethics of military intervention.

My master’s thesis focused on the Allied occupation of Ethiopia 1940-1943, which was meant to give some kind of insight into how armies best invade, hold and then release a country to self-rule.

And from that perspective, what I’m reading today reminds me a lot of the papers I used to pull out of the British archives. Unlike the frozen folders of antique yellowed and brittle documents, however, in this case I wish I had been given a chance to review or edit this article before it went to press to help eliminate such a glaring error.

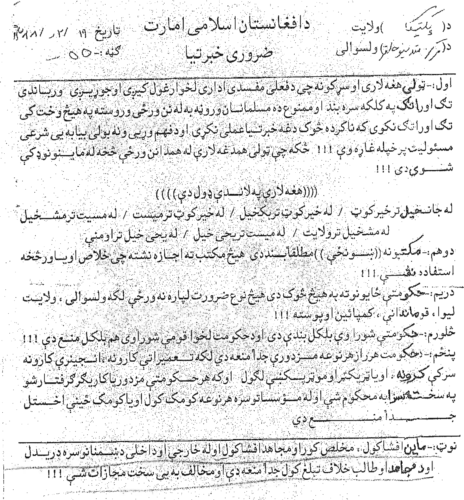

In the 1980s under Ronald Reagan American military intelligence plastered Afghanistan with posters like the following one, promoting violent religious extremism as a form of invincibility.

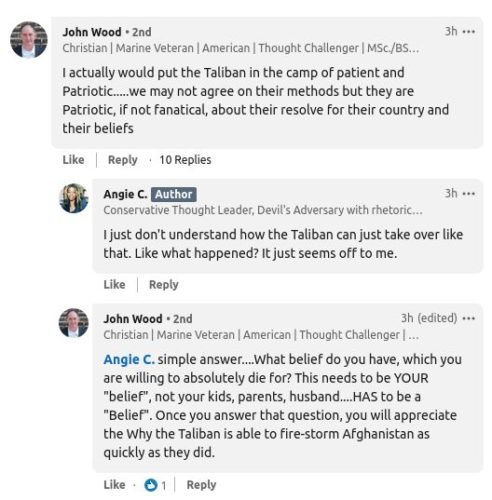

That old propaganda campaign has come full circle now, as I see very similar thinking (obviously seeded by Russian military intelligence) being propagated by posters (pun intended) on LinkedIn.

Doesn’t that look a lot like a clumsily-worded explanation for the cartoon above?

Is this language being used by John Wood not also terrorism recruitment? It appears to be goading people into joining a “belief” system by promising a magic ability to violently and quickly overthrow their government.

Of course no such magic exists, this is disinformation. And of course that’s not even close to the truth about Afghanistan or why the Taliban were able to roll through territory so quickly.

Hint: they leveraged Twitter and motorcycles, a modern take on the Russian “speed, momentum and violence of action” doctrine (although it reminds me also of American “evolution of revolution” in the 1986 Toyota war and the Japanese on bicycles seizing Singapore rapidly in 1941).

Even more to the point I find it infuriating to see Americans try to blame the soldier who is unfed and unpaid, lacks fuel and ammunition, and faces the very real issue of his family being unprotected at home as the Taliban advance to kill them.

People sitting in their comfy chair banging on a social media comment box, spreading toxic and cheap narratives like “they should have fought harder” are a total disgrace to humanity — an insult to the nearly 70K who sacrificed everything fighting for their country.

If anyone wants to talk about serious issues related to soldier morale, it was a US President’s flimsy negotiations with the Taliban behind the back of an elected Afghan government that set the tone from the top as a clear act of bad faith.

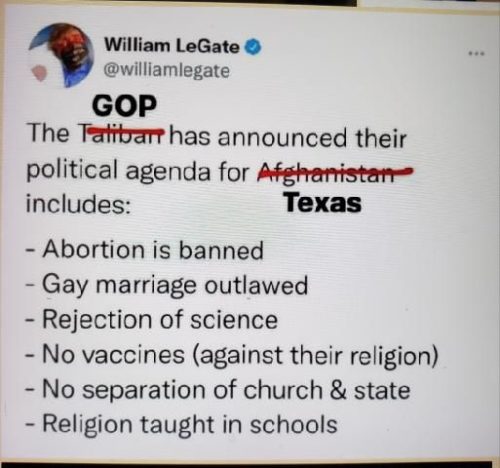

Speaking of Twitter, here is a more clear-eyed take on what LinkedIn should be talking about:

If the Taliban returns to power, I along with other women…will either be stoned to death or executed in a public space in front of a crowd.

Women now are expected to lose everything.

If that sounds like a foreign policy issue, in reality this is just as much a domestic one for America. Can you tell which one is which?

Now might be a great time to remember that Ronald Reagan not only as President claimed the Mujaheddin (religious extremists who violently subjugated women) were “like our founding fathers”, he also repeatedly cited a man named Winthrop in his speeches about America.

Winthrop was a religious leader who subjugated women, calling them agents of the devil.

America finally switched sides in 1996 to fight against religious extremism in Afghanistan, which is also when the discussion started to bloom about rights of women in Afghanistan despite it being obviously late.

The Mujahedeen period (1992-1996) was marked by ferocious, internecine warfare that scarred all aspects of Afghan life. Women’s rights and freedoms were severely restricted. Grave human rights abuses included extra-judicial executions, torture, sexual violence, disappearances, displacement, forced marriage, trafficking and abduction. This period represents one of the darkest chapters in the history of Afghan women. The brutality and predatory nature of the civil war, or Mujahedeen period, contributed to the emergence of the Taliban and their consolidation of power throughout much of the country after their capture of Kabul, September 1996.

It’s kind of a recent thing, in other words, for the American government to officially care about ending the oppression of women and children. Slow and late, as the author Ghost Wars explained a long time ago:

…individuals inside the US bureaucracy, at the state department, elsewhere, who began to warn that the United States needed to change its political approach to this covert [support of Mujahedeen], that they needed now to start getting involved in the messy business of Afghan politics and to start to promote more centrist factions and to negotiate compromise with the Soviet-backed communist government in Kabul to prevent Islamist extremists from coming to power as the Soviets withdrew. These warnings, when you look at them with the benefit of hindsight, are quite prescient and certainly were strongly given, but they languished in the middle of the bureaucracy and were largely ignored by both second term Reagan administration and the first Bush administration…

In September 2007 the House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs held a hearing where Chairman Lantos gave a retrospective and put it like this:

America should not be in the business of arming, training and funding both sides of a religious civil war in Iraq. Did the Administration learn nothing from our country’s actions in Afghanistan two decades ago, when by supporting Islamist militants against the Soviet Union, we helped pave the way for the rise of the Taliban?

When LinkedIn posted the above propaganda it seems they are rolling back time to a genuinely awful American ignorance and flirtation with tyranny, as well as exposing the tools of Russian military intelligence today.

Neither are ok, of course.

To be fair it is being said now that neither Russia nor China are pleased by Islamic extremism taking control of Afghanistan.

They fear that a revival of the harsh Islamist code and rule by intimidation that underpinned the fundamentalist group’s government in the 1990s would lead to a resurgence of Muslim extremists.

The emerging geopolitical quagmire doesn’t mean that Russia will pass up the opportunity to use anti-democratic religious recruitment propaganda of the Taliban to destabilize America.

It’s a shame to see LinkedIn facilitating the posters. If we were talking about WWII they would most certainly be censored. Or as an article in Business Insider recently put it:

“To counter Chinese and Russian IO, we need to be aware of the threat and educate the public,” the retired special-operations PSYOP soldier said. “Americans need to understand that this is a real, ongoing threat. Sometimes war doesn’t mean gunfire and explosions.”

Where are the grey hats?