A new documentary has been released called “Bisbee ’17” about American life under President Wilson after his successful 1916 “America First” campaign. NPR gives us the synopsis of the Bisbee Deportation story:

The event itself has become known as the Bisbee Deportation. On July 12, 1917, roughly 1,200 copper miners, who’d been striking for better wages and safer working conditions, were rounded up at gunpoint, some by their own relatives, and sent via cattle car to the New Mexican desert, where they were left to die.

[…]

People to this day in the town believe that the deportation was correct and right. And they sympathize with the people who carried it out, particularly people who are descendants of people who had a hand in it.

[…]

When you go through that list of deputies, you see that there is one Slavic name. Everybody else is an Anglo-Saxon. So my conclusion – after all of this research, the deportation was not a response to a labor action. It was that to a limited extent, but it was also in the nature of an ethnic cleansing.

What the documentary, and NPR for that matter, do not reveal is why ethnic cleansing would be so topical in 1916. In short, Woodrow Wilson effectively restarted the KKK in 1915 after it had all but disappeared, and Bisbee is a reflection of that sentiment.

What caused the KKK decline and why did Wilson bring it back?

I will try to briefly explain. It starts with President Grant signing into law the creation of a Department of Justice (DoJ) in order to aid in the prosecution of white supremacists, since they were refusing after the Civil War to accept blacks as citizens. Grant wanted to use non-military measures to protect 13, 14 and 15 Amendments to the Constitution from domestic terror threats.

The DoJ itself buries these civil rights foundations of its origin in this rather bland retelling on their official website:

By 1870, after the end of the Civil War, the increase in the amount of litigation involving the United States had required the very expensive retention of a large number of private attorneys to handle the workload. A concerned Congress passed the Act to Establish the Department of Justice (ch. 150, 16 Stat. 162), creating “an executive department of the government of the United States” with the Attorney General as its head.

That “increase in the amount of litigation involving the United States” means white supremacists.

In other words, Grant greatly expanded the Attorney General role from Judiciary Act origins of 1789, basically a one-man advisory concept, to a systematic government arm to protect the Union against domestic threats. This new much broader departmental remit with branches was resourced to fight white supremacists nationally. President Grant basically pushed out a peace-time organization specifically to fight pro-slavery militants who continued to refuse to lay down their arms after he had forced their official surrender in war. This is what caused the KKK to decline.

Why was General Grant, now President Grant, faced with this problem?

Sadly in 1866 just a year after Lincoln’s assassination, President “this is a country for white men” Johnson was repeatedly trying to block blacks getting rights. Despite Johnson’s efforts the Thirteenth Amendment was passed in 1866 abolishing slavery, which pro-slavery militants considered an assault on their “economic freedom” to be a white supremacist:

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction

The failure of Johnson to block civil rights legislation angered violent white supremacist militants and they rebelled again to prevent peace. Despite decisively losing the Civil War to General Grant, pro-slavery militants after the assassination of President Lincoln created the KKK under President Johnson to use veil of night and disguise to continue terror campaigns against Americans abolishing slavery. Within two years by 1868 the KKK was running numerous violent terror campaigns to prevent reconciliation, murder blacks and sabotage Thirteenth Amendment labor rights.

This is why President “Let Us Have Peace” Grant’s election in 1868, and his creation of the first real DoJ in America in July of 1870, were seminal moments in the fight against white supremacists. The candidate Grant ran against had a campaign slogan, like President Johnson’s reputation, of “This is a White Man’s Country. Let White Men Rule.”

Grant had won the war, now he won the Presidency and was about to take down the same people for the same reasons, this time with non-violent means. A month after DoJ was created, August of 1870, a Federal Grand Jury declared the KKK a terrorist organisation. President Grant then further established remedies for these domestic terrorists in 1871 by signing an Enforcement Act, which made it illegal for private conspiracies (e.g. KKK) to deny civil rights of others. He pursued in peace the same anti-American forces he already had decisively beaten in war, and again he brilliantly led the country away from its violently racist detractors.

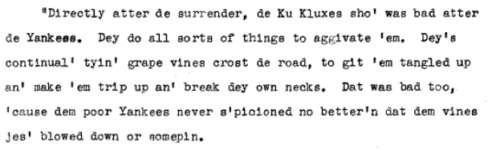

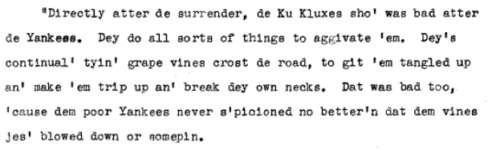

Here’s testimony from an emancipated slave, who explains how the KKK immediately after Civil War ended began their domestic terror tactics like placing hidden traps on roads and killing American soldiers.

While it is tempting to frame the sad white supremacist chapters of American history entirely in terms of Civil War and enslavement of blacks, we can not overlook the broader picture of the late 1800s and how the KKK was a symptom of racism and wrongs more broadly found in American history:

- 1871 hundreds of armed whites entered “Negro Alley” to murder Los Angeles’ Chinese residents

- 1885 white supremacist “Knights of Labor” group fomented a Rock Springs massacre that left dozens of Chinese miners dead

- 1887 white “schoolboys” tortured and murdered thirty-four Chinese miners in Oregon

- 1897 Lattimer massacre saw Polish, Slovak, Lithuanian and German miners shot in the back and killed; the sheriff decided to end labor protests by murdering protesters

Grant’s focus on enforcing civil rights was meant as an end to slave labor that the white supremacists fought so hard to preserve. The story of white supremacists in American using terror tactics really has a broader topic of wage disputes and labor rights with non-whites. But the reason the KKK in particular is significant to the Bisbee story is Grant’s strong leadership meant the KKK made less of a name for itself over the subsequent decades until things changed in 1915.

That is when “the 20th Century KKK” was initiated, infamously associated with President Wilson’s screening of a white supremacist propaganda and isolationist views of the world/immigration. It is the timing of a second KKK that should be noted as backdrop to this movie.

While the original KKK formation under President Johnson had used domestic terror to undermine the Thirteenth Amendment and deny freed slaves their civil rights, this recast formation was a “labor-oriented” terror organization targeting immigrants and their religions, which is how the “America First” campaign of President Wilson brought back the KKK that President Grant had ended.

The Bisbee story thus is a clear reflection of the KKK second rise, a “reaction” to civil rights being granted to non-whites such as Irish, Germans, Poles, Lithuanians, Slovaks, Mexicans, Chinese, Jews, Catholics…. All of these groups were targeted under the guise of “labor-oriented” action by the KKK during President Wilson’s administration, just as blacks had been murdered by the KKK under President Johnson’s administration.