In a nutshell, traditional definitions of war linked to kinetic action and physical space are being framed as overly restrictive given a desire by some to engage in offensive attacks online. The head of NSA is asking whether reducing that link and authorizing cyber attack within a new definition of “war” would affect the “comfort” of those holding responsibility.

“[On offense] the area where I think we still need to get a little more speed and agility — and as Mr. Rapuano indicated it is an area that is currently under review right now — what is the level of comfort in applying those capabilities outside designated areas of hostility,” Rogers asked out loud.

“I don’t believe anyone should grant Cyber Command or Adm. Rogers a blank ticket to do whatever you want, that is not appropriate. The part I am trying to figure out is what is the appropriate balance to ensure the broader set of stakeholders have a voice.”

Rapuano also referenced challenges associated with defining “war” in the context of cyber, which can be borderless due to the interconnected nature of the internet.

“In a domain that is so novel in many respects, and for which we do not have the empirical data and experience associated with military operations per say particularly outside areas of conflict, there are some relatively ambiguous areas around ‘well what constitutes traditional military activities,'” said Rapuano. “This is something that we are looking at within the administration and we’ve had a number of discussions with members and your staffs; so that’s an area we’re looking at to understand the trades and implications of changing the current definition.”

While I enjoy people characterizing the cyber domain as novel and border-less, let’s not kid ourselves too much. The Internet has far more borders and controls established, let alone a capability to deploy more at speed, given they are primarily software based. I can deploy over 40,000 new domains with high walls in 24 hours and there’s simply no way to leverage borders as effectively in a physical world.

Even more to the point I can distribute keys to access in such a way that it spans authorities and bureaucratically slows any attempts to break in, thus raising a far stronger multi-jurisdictional border to entry than any physical crossing.

We do ourselves no favors pretending technology is always weaker, disallowing for the prospect of a shift to stronger boundaries of less cost, and forgetting that Internet engineering is not so much truly novel as a revision of prior attempts in history (e.g. evolution of transit systems).

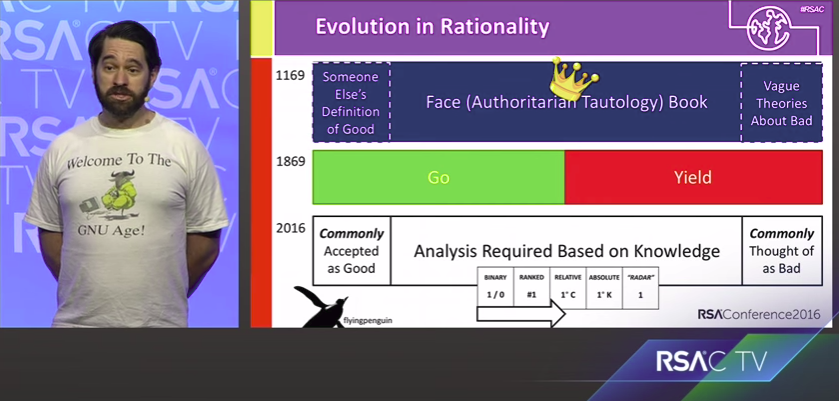

My recent talk at AppSecCali for example points out how barbed wire combined with repeating rifles established borders faster and more effectively than the far more “physical” barriers that came before. Now imagine someone in the 1800s calling a giant field with barbed wire border-less because it was harder for them to see in the same context as a river or mountain…