The recent case of a Harvard scientist – facing Trumped up criminal charges to contrive her deportation to Russia – bears disturbing similarities to historical patterns of scientific persecution.

Kseniia Petrova, a Harvard scientist, has been in a correctional facility in Louisiana for the past three months since being detained.

Examining the Nazi targeting of scientists reveals patterns that help contextualize current American concerns.

The Nazi Blueprint for Scientific Suppression

- Legal and Administrative Mechanisms

The Nazi assault on science began with the seemingly bureaucratic “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service” in April 1933. This measure removed Jews and political opponents from academic positions, displacing over 1,600 scholars including Nobel laureates Albert Einstein, Max Born, and James Franck. - Border Control as Scientific Control

As conditions worsened, the regime weaponized border controls and passport restrictions. Scientists found their travel documents invalidated or were denied permission to take research materials out of the country. Those with international connections were particularly targeted as potential “knowledge transferors.” - Forced Returns and Exploitation

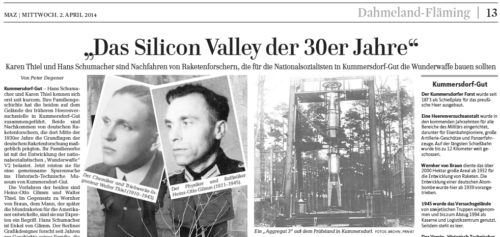

For scientists who escaped, the regime attempted to force their return through family threats, citizenship revocation, and property confiscation. Those who remained faced an impossible choice: abandon their work or serve the regime, as exemplified by Werner Heisenberg’s eventual leadership of the German nuclear program or chemist Walter Thiel’s slaves of “1930s Silicon Valley” forced by him to develop rocket propulsion for bombing UK cities.

Source: Märkische Allgemeine Zeitung (MAZ), a regional newspaper in Brandenburg, Germany; an area known for harboring and promoting Nazi sentiment (e.g. AfD).

Petrova’s Case: Disturbing Parallels

Petrova’s situation contains alarming echoes of this pattern:

A tiny, minor customs infraction (failing to declare scientific samples for her own science lab) escalated without explanation through immediate visa cancellation, prompting Judge Reiss to question, “Where does a customs and border patrol officer have the authority on his or her own to revoke a visa?”

The answer comes from 1930s Nazi German history, which modeled itself on America First doctrines of the late 1800s. The systems of oppression relied heavily on lower-level officials who took local initiative to implement what they perceived as Hitler’s will, often without explicit orders – a symptom of fascism historians recognize as “working towards the Führer.”

Nazi border officials and customs agents were among the first to exercise broad discretionary powers that went beyond their formal authority. They would often make life-altering decisions about who could leave the country and what they could take with them, who could live or die, similar to the customs officer in Petrova’s case unilaterally revoking her visa.

This administrative overreach was central to how the Nazi system operated. Officials at all levels began taking actions they believed aligned with the regime’s goals without needing explicit directives. This is documented in cases where customs officials prevented scientists from taking research materials or personal belongings when leaving Germany, even when there was no formal law prohibiting it.

Ian Kershaw, a prominent historian of Nazi Germany, described this phenomenon where lower-level bureaucrats would “anticipate the Führer’s wishes” and act on their own initiative to implement what they believed leadership wanted – often going beyond their formal authority. The result was a system where persecution could operate through seemingly mundane administrative channels without requiring explicit orders from the top.

…radicalisation and atrocities in Nazi Germany were often driven by subordinates competing for advancement and aiming to follow Hitler’s broadly outlined wishes.

The intention to deport Petrova to Russia, a country she fled in 2022 fearing political persecution, closely mirrors the cruel Nazi practice of forced returns that refugee scientists of the 1930s “Silicon Valley” death camps dreaded for reasons obvious today.

The timing of her alleged criminal charges – filed three months after detention and immediately following a judge’s scheduling of a bail hearing – reveals these charges may be a specific loophole to undermine the law, a mechanism to ensure continued detention rather than admit the actual infraction is too tiny to even warrant detention.

The broader pattern affecting other academics creates what Massachusetts Attorney General called a “reckless and cruel misuse of power to punish and terrorize noncitizen members of the academic community.” Academia is expected now to be punished in America for acts of scientific rigor and integrity, rewarded only for displays of devotion and loyalty to Trump.

Consequences and Lessons

The Nazi persecution created the greatest intellectual migration in history, with Germany losing approximately 25% of its physics, chemistry, and mathematics faculty by the 1938 systematic Nazi acts of book burning.

…let’s be honest: this kind of hate doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It’s part of a disturbing wave we’re seeing across the country. A wave enabled – sometimes with a wink and a nod, sometimes with a bullhorn—by leaders who should know better than to fan the flames of division for political gain.

The politically driven Nazi brain drain devastated German science (leaving their Army powered mostly by horses and slaves in WWII) while strengthening American institutions where immigration and diversity of voices were welcomed.

The Nazi-like realignment of science in America today risks not just individual careers but entire research networks, as Harvard researcher Adam Sychla noted: “I easily could have met her last week to start a collaboration. Instead, Kseniia is being unfairly detained.”

The scientific community’s response matters greatly. In the 1930s, organizations like the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced German Scholars helped hundreds escape persecution. Today, the Harvard students and faculty who traveled to support Petrova demonstrate recognition of what’s at stake: not just one scientist’s freedom, but the principle that science must remain beyond the reach of political persecution.

[President] Macron reiterated that the Choose France for Science initiative, launched a few weeks ago, “generated over 30,000 visits, one-third from the United States, with several hundred application files opened”. The goal is to “welcome talent at every level, from PhD students to Nobel laureates, including post-docs and junior professors, based solely on the quality of their work”.

How the world responds to such cases will determine not just individual fates but also the future of international scientific collaboration and America’s position for scientific talent fleeing persecution. On the face of it, deporting a Harvard scientist to Russia without cause is a cruel, undemocratic and self-defeating act of a petty autocrat bullying the scientific community. Europe, Australia and Canada stand to “brain gain” individually as well as align more together against such acts of the sewage-contaminated American regime.