Let’s talk about deep historical currents behind a new book called “The Singing Word: 168 Years of Atlantic Poetry“.

Walt Hunter’s “The Singing Word” lands today, and it represents far more than a simple anthology of American verse. This collection of 168 years of Atlantic poetry embodies a profound act of historical continuity, a legacy that traces directly back to one of the most shameful episodes of presidential overreach in American history.

President Jackson Assaulted Free Expression

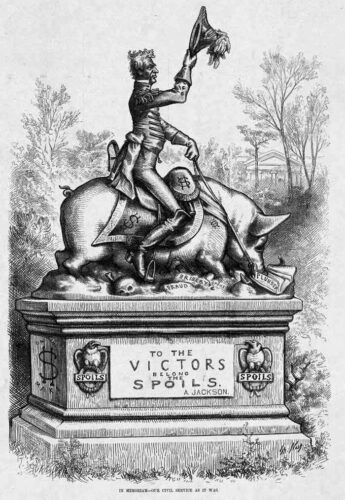

Foundational DNA of The Atlantic comes from the postal crisis of 1835 that helped catalyze the magazine’s eventual creation. President Andrew Jackson, faced with the American Anti-Slavery Society’s “Great Postal Campaign”—an effort to educate and liberate the South with over 100,000 prints of abolitionist literature—responded with what can only be described as state-sanctioned censorship.

For example, on July 29, 1835, the Post Office was raided in Charleston by a white supremacist mob calling themselves “The Lynch Men.” They seized bags of newspapers and burned them in a massive bonfire, along with effigies of leading abolitionists, before a crowd of nearly 3,000 people. But the truly shocking aspect wasn’t the mob violence, because it was President Jackson’s response.

Rather than defending the American founding fathers’ beliefs in sanctity of privacy in mail and the First Amendment, Jackson encouraged and inflamed the censorship. His Postmaster General, Amos Kendall, was ordered explicitly to arm Southern postmasters with permission to refuse delivery of materials they opened and disagreed with, arguing they had a “higher obligation” to preserving slavery in their communities than to federal law. Jackson even included condemnation of the abolitionists in his 1835 State of the Union address, calling American freedom fighters the “monsters” who should “die,” and advocated for federal legislation that would authorize postal surveillance and censorship of “incendiary” anti-slavery materials.

This was America’s big test in federal mail surveillance and censorship a precedent that would echo through McCarthyism to modern NSA overreach in Room 641a.

The Literary Counterrevolution

Jackson’s presidency by 1857 had ended two decades earlier, but the intellectual wound he inflicted on American discourse had not healed. The transcendentalist movement, centered in Boston and Concord, had watched in horror as democratic principles buckled under pressure from slavery’s defenders and their presidential enabler.

When publisher Frank Underwood approached the New England literary elite about founding a new magazine, he found a receptive audience among writers who had lived through Jackson’s assault on free expression. The Atlantic Monthly, launched in November 1857, was explicitly conceived as an anti-slavery publication that would provide what one editor called “cultural leadership” to counter the “cultural leveling” they saw as inherent in Jacksonian democracy.

The magazine’s founding circle reads like a who’s who of American intellectual resistance to Jacksonian authoritarianism: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and John Greenleaf Whittier. These were not merely literary figures—they were conscious architects of what they hoped would be a more enlightened American discourse.

Significantly, the magazine’s very first poem of national prominence was Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride,” which appeared in 1861. The timing was no accident: as the Civil War began, The Atlantic was deliberately invoking the Revolutionary War’s spirit of resistance to tyranny—a not-so-subtle rebuke to Jackson’s legacy and the Southern rebellion it had helped nurture.

Poetry as Political Resistance

The Atlantic’s poetry from its earliest years reveals a publication acutely conscious of literature’s political power. Julia Ward Howe’s “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” which appeared as the magazine’s lead story in February 1862, wasn’t merely patriotic verse—it was a direct answer to the Confederate appropriation of American symbols and a conscious effort to reclaim the moral authority that Jackson’s administration had ceded to slavery’s defenders.

The magazine understood what Jackson had proven: that controlling discourse meant controlling democracy. If the President could declare certain ideas too dangerous for the mailbox, then independent media became essential to preserving the “unfinished project of the nation”—a phrase Hunter uses to describe The Atlantic’s ongoing mission.

Contemporary Echoes

Hunter’s organizational framework for “The Singing Word”—dividing the collection into “National Anthems,” “Natural Lines,” and “Personal Mythologies”—reflects this historical awareness. The “National Anthems” section particularly resonates with The Atlantic’s founding purpose: providing alternative visions of American identity that could compete with authoritarian populism.

In his curatorial statement, Hunter explicitly connects past and present:

What emerged as I read was an optimism and realism—a sense that, however bad things are, the idea of America is worth fighting for, and worth questioning and scrutinizing in new ways.

This language deliberately echoes the rhetoric of The Atlantic’s founders, who saw themselves as defending American ideals against their political corruption.

The anthology’s span from 1857 to 2024 encompasses not just the Civil War era that birthed the magazine, but also Reconstruction, the World Wars, the Civil Rights Movement, and our current moment of democratic stress. Each era has produced its own version of Jacksonian authoritarianism, and each has found The Atlantic publishing poetry that serves as both witness and resistance.

An Unbroken Line

When we consider poets like Robert Frost wrestling with American identity in “The Gift Outright,” or Adrienne Rich challenging power structures in her feminist verse, or contemporary voices like Juan Felipe Herrera expanding the definition of American poetry itself, we see the same impulse that drove Emerson and Longfellow to found The Atlantic: the conviction that literature must engage with democracy’s ongoing struggles.

Hunter’s collection thus represents more than literary archaeology. It documents an unbroken tradition of American writers using verse to contest official narratives, expand democratic participation, and preserve space for dissenting voices—precisely what Jackson’s postal censorship attempted to eliminate.

The Stakes of Literary Memory

“The Singing Word” arrives at a moment when democratic norms face renewed pressure. The anthology’s subtitle, “168 Years of Atlantic Poetry,” quietly asserts the durability of institutions that defend free expression against authoritarian assault. By bringing together voices from Longfellow to Limón, including poets “whose work has never before been published outside of the magazine,” Hunter demonstrates how literary institutions can preserve and amplify voices that might otherwise be silenced.

The collection’s price and wide distribution through major retailers represents another form of resistance to Trump/Jackson corruption and elitism. While Jackson used federal power to suppress abolitionist literature, The Atlantic uses democratic capitalism to ensure its counter-narrative reaches the broadest possible audience.

In this light, “The Singing Word” becomes not just an anthology but a manifesto: proof that American literature at its best serves as democracy’s memory, its conscience, and its most persistent hope for renewal. The poets collected in Hunter’s anthology didn’t just document American experience—they fought for the right to define it against those who would narrow its possibilities.

From the ashes of Jackson’s postal bonfires to the digital age of “The Singing Word,” The Atlantic’s poetry represents 168 years of resistance to the authoritarian impulse, which once again is closing the door on American democracy. In our own moment of political extremism and media manipulation, this anthology arrives as both historical witness and contemporary call to arms: proof that the republic of letters remains a reliable guardian of democratic expression.

“The Singing Word: 168 Years of Atlantic Poetry,” edited by Walt Hunter, was published by Atlantic Editions on September 9, 2025.