When Italian commuters see a costume, what are they actually seeing? A new Mental Health Research paper claims seeing Batman on their train will nudge people in a predictable and “prosocial” way.

This study tested whether an unexpected event, such as the presence of a person dressed as Batman, could increase prosocial behavior by disrupting routine and enhancing attention to the present moment. We conducted a quasi-experimental field study on the Milan metro, observing 138 rides. In the control condition, a female experimenter, appearing pregnant, boarded the train with an observer. In the experimental condition, an additional experimenter dressed as Batman entered from another door.

The problem is the researchers assumed they know before they know. They didn’t really ask the question they claim to be studying. They crudely imported an American pop-psychology reading of superheroes-as-uncomplicated-good, which isn’t even close to reality, and then built a study around it.

Batman is… NOT clearly prosocial.

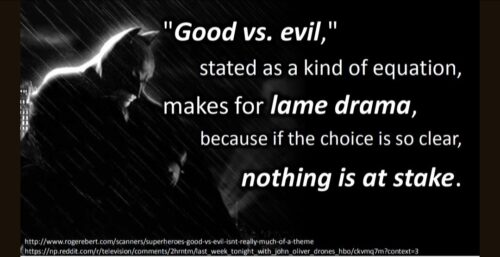

Batman is more like a troubled soul, controversial at best, which is the whole point of Batman.

His story works narratively because he’s morally ambiguous. He’s not Superman. You’re supposed to be uncomfortable with his outsider power. Is he helping, or is he the one creating conditions for escalating violence? Is he protecting Gotham, or feeding his own pathology? Who came first, the villain or the hero, the mob or the law? These are the questions of public representation and personal identity the “dark” Batman costume invokes.

This connects to broader critiques of how research sometimes works: the interpretive framework precedes the data collection, shapes what questions get asked, determines what counts as a finding.

These researchers didn’t discover a “Batman effect.” They constructed this concept on flimsy scaffolding. They fabricated conclusions that Batman could signify prosocial values, and then measured something that happened in order to correlate with their stimulus.

A full 44% who reported they didn’t even see Batman (another critical element to his story arc) are doing more honest epistemology than the researchers. They’re saying “I don’t know why I did that.”

This raises another interesting thing about Batman that he’s like a black bat in the dark, hiding at night, unseen and unknown, and not a clean moral symbol. He isn’t supposed to be seen.

The drama exists because a choice isn’t clear, because something is at stake, because the character embodies genuine ethical tension. And in the study they even note they omitted the full mask “for ethical reasons” to avoid scaring passengers, which seems like an admission that the visage itself carries threat, not prosocial nudges.

The deeper tension and balance has been featured in the ethics courses I have been teaching for over a decade to computer science graduate students.

Yet here come researchers in November 2025 flattening all of history into shallow “American superhero is positive symbolism for prosocial priming.”

They’ve taken nuance of a troubled figure, whose entire cultural function is problematic urban vigilantism, extralegal violence, and the relationship between trauma and corrupt justice, and reduced him by their own definition to… a happy face with a cape?

Let’s be honest. Batman is essentially a one-man surveillance state with a monopoly on extrajudicial violence. He’s what happens when someone with unaccountable resources decides representative systems have failed and takes enforcement into his own hands.

That’s not inherently a hero, that’s a threat model.

And yet their only comparison seems to be the Batman costume versus no unusual stimulus. They have no conditions testing whether the effect comes from costume novelty itself or generally, from positive superhero symbolism specifically, from the Batman character in particular, or from any unexpected human presence that breaks routine.

What if the Milan metro passengers weren’t being primed toward heroism by a vigilante comic but were experiencing something else entirely? Unease at a costumed figure. Heightened alertness that reads as threat-awareness rather than mindfulness. A desire to perform normalcy and virtue in the presence of something ambiguously transgressive. Or simply confusion that happens to correlate with compliance, which is the pique technique they mention but don’t privilege.

The researchers didn’t interview passengers about their actual Batman associations. They asked why people offered seats (answers: pregnancy, social norms) and whether they even saw Batman. They never asked what Batman meant to those who saw him.

People might associate any costumed figure with football ultras, with protest, with street performance soliciting money, with mental illness, with an extrajudicial vigilante threat like the actual Batman story.

Batman as an unambiguous positive superhero is a fiction itself, and added externally to his problematic visage. The entire interpretive framework for this study, that Batman primes heroic helping, is an untested assumption that is being smuggled in by researchers to drive a false premise.

The authors even acknowledge in their paper that social priming research has largely failed to replicate, then proceed to build their entire interpretation on it anyway. They’re essentially saying “we don’t know why this works, and the theory we’d like to invoke has a replication crisis.”

They have theories but can not distinguish between environmental novelty and helping behavior.

Sigh.

The fictional narratives of Batman have been far more epistemologically sophisticated than this professional framework supposedly grounded in reality.