Since 2004 I have been driving a diesel engine. The B5.5 generation VW Passat gets about 40 mpg despite being a full-sized vehicle with the towing strength equivalent of a Ford F150 pickup. It’s really quite amazing to consider how efficient it runs. On a trip from San Francisco to Las Vegas, which is approximately 600 miles, I did not have to stop to refuel and saved almost an hour off the total time.

Even a small time spent looking at or driving a modern diesel vehicle tends to teach you several things about diesel myths:

- They’re expensive: Despite being loaded with all the possible upgrades diesel cars can be less expensive off the line than a gasoline equivalent model. I paid $5K LESS in 2004 to get a diesel Passat instead of gasoline. When I told others they went to the dealer and confirmed the same thing. My parents bought a brand new 2005 VW Passat TDI after they saw the sticker price was lower than the sticker on gasoline. Diesel vehicles apparently can be priced very competitively. And then, after paying less, the value of my car actually increased.

Some suggest diesel engines now must be more durable (due to compression load and high-pressure) and therefore more expensive to build than a gasoline engine. This is not, however, an argument against diesel. It could be another reason FOR buying diesel; a lot like saying a larger more powerful gasoline engine will be more expensive to build than a weaker small and inefficient one. Charging a premium for better performance/efficiency/durability obviously is no real barrier for auto sales, right Ford Tough?

- They’re noisy: Disesel vehicles are quiet, really quiet. I’ve said this before but when the Audi and Peugeot hugely powerful (1,000 ft/lb torque) supercars the 24 hours of Le Mans the fans told me they were disappointed. They no longer could hear the roar of engines from cars in the lead. These engines are incredibly powerful yet understated. The vehicles that lost after stopping to be refueled more often, such as Ferraris, Porsches and Corvettes, were the engines that made the most noise.

Consider also that my mother, a professor who studied sound, in 2005 said she did not like the idea of buying a diesel because of the reputation for noise. She was bracing for what she had been told would be the stereotypical “clatter”. However, when she sat down in the actual car for a test drive she said with delight “It purrs like a cat!” Seven years later she bought a second diesel and she says it is practically silent. This is no coincidence. Diesel engines run at lower revolutions to achieve power and therefore are quieter.

- They’re anemic: Torque is an amazing thing for driving. Horsepower is what most people are used to in America. The horsepower feels great when you want to get going because you can rev an engine through a long curve. Step on the pedal and you might not take off right away but you can accelerate through 4000 rpm. It turns out torque is really what matters most. Driving up a hill at 65 mph and want to avoid shifting down? You need torque. Driving a car full of family and groceries yet trying to pass another car and want to avoid shifting down? You need torque. Torque is not only great for pulling weight, it also is great for getting started at slow or low speeds such as driving in slippery conditions.

Diesels have a lot of torque but they also tend to have a short curve of power. Starting from a stop they can kick but then feel hesitant/gutless compared to a gasoline engine. This is typically resolved by the addition of a turbo to push through the upper end of a curve. Some even have twin turbos and/or technology to eliminate the lag when engaging a turbo. If you have ever been pushing a diesel pedal when the turbo fails you will be faced with the undeniable realization that it is a completely different beast than gasoline; some extra technology is needed to give it the exhiliration of horsepower.

Another way of looking at this is the average mileage of diesel is impacted by stop-and-go. 40 mpg is easy on the highway because there’s almost no need to touch the pedal (due to power at the low end of the curve) but if you stop for a lot of red lights you have no choice but to waste fuel as you run into high RPMs. Another point on torque, My VW Passat wagon is a 4 cylinder engine. The power it produces at low RPM is comparable to a 6 cylinder gasoline engine. That’s why diesel cars can be made with smaller, lighter engines yet have reasonable power.

- There’s no room for improvement: The improvement over just a few years has been amazing. More efficient injectors, cleaner emissions, quieter, smoother…the list goes on and on. Innovation has allowed the latest VW diesels to achieve 90 mpg in track tests and 84 mpg in real-world use. Honda says its new Civic diesel engine runs 79 mpg with 221 ft-lb torque and is the lightest in its class. Subaru calls its 2005 boxer diesel engine a “True Engineering Revolution”

When Subaru started its development project for the BOXER DIESEL, we soon realized that we were in an unprecedented, unchartered area in diesel engine development and were undertaking a technological challenge for which no benchmarking comparisons existed.

You also could simply follow Catepillar’s diesel innovation marketing from 2001 (clean bus fleets) to 2005 (low emission trucks) to 2012 (near zero emissions). Outside the consumer automobile, diesel is marketed with many amazing innovations. I’ve been eyeing the Volvo diesel hybrid (already sold-out for 2013) because it gets 126 or better mpg yet has the torque and all wheel drive of a truck combined with the performance of a Ferrari 308.

Perhaps you can see why I am so eager to stay with diesel when I move to a hybrid vehicle. Given that we’re only just starting to see the potential innovation in both diesel and electric technology we could be on the verge of a vehicle revolution. Imagine combining the performance of a sports car, power of a utility truck and the efficiency of a daily driver into a single vehicle. That is what we see already in the first diesel electric hybrids.

Obviously an electric engine eliminates the stop/go mileage issue completely. Diesel only would be needed at speed and long distances, where it is getting more efficient every year. In other words:

It might sound obvious but I have to stop now and reflect on a strangely opposite view from a site called Green Car Reports. John Voelcker wrote an opinion piece called “Diesel Hybrids: Why They Don’t Make As Much Sense As You Think“. His arguments against using diesel hybrids are the following:

- “First and foremost is the issue of cost. On average, a diesel engine costs about 15 percent more to manufacture than a gasoline engine of equal output.”

- “…a diesel hybrid should have boatloads of torque off the line, but may require extensive gearing to ensure highly efficient running at speed.”

- “Gasoline engines convert 25 to 30 percent of a fuel’s energy content into forward motion at the wheels; the rest is wasted as heat and noise. By contrast, a diesel converts 30 to 35 percent of the fuel’s energy into forward motion–hence the higher fuel efficiency figures. But that leaves less “headroom” for improvement.”

Ugh. No, really. Ugh. I want to put John in a diesel just for a day so he can feel how utterly wrong he is on point number two.

A horsepower curve continues well beyond the diesel curve as explained by The Institute of Motor Industry. The diesel has to shift or hit a turbo to get through the full acceleration path while a gasoline engine just revs higher and higher. What this really means is that he is flat wrong; diesel is a better match for hybrid because electric can carry the start to speed and then leave diesel to maintain speed with efficiency (as it does already). This is a PERFECT application of the electric engine that has NO CURVE. Let it take over starts/stops and you have a beautiful marriage of technology. John would instinctively know this if he drove a diesel.

Now back to point number one and the matter of cost.

I call bullshit. Cost is 15% more for an engine of equal output? Let’s see the numbers on that unbelievable statement. Are we measuring patent application fees or what? Rather than get tied down in an inventory of parts and labor, however, let’s get straight to the point. Nobody thinks the Ford Raptor is an inexpensive vehicle. A stock sports truck ready to chew up Baja desert at 60 mph starts at $45K; and probably not one single Raptor sold will ever actually be used for what it was designed. So cost can be higher and people gladly pay more for it because of percieved and realized value, period.

Even if I go along with the unbelievable point that the diesel engine costs 15% more for “equal output”, in terms of value it kills a gasoline engine with a longer life and higher efficiency. Go tell a family of four that they will have to visit the pump half as often and they will be glad to pay a premium. Just the other day a couple with a newborn child pulled up and told me they switched from a Tahoe to a Jetta TDI when they realized they would go from refueling every week to once a month. What is the value of all that time gained to parents of a newborn? John’s 15% cost worry simply evaporates in the face of some common sense. It seems to me the new diesel engines are in fact lighter, smaller and less-expensive to build and maintain over time than gasoline engines.

Now on to his third point.

He says there’s no “headroom” for improvement. This is completely backwards logic.

If you give me the option of a diesel-hybrid high-performance full-sized sports-wagon that gets 120+ mpg (Volvo V60) or a gasoline-hybrid lightweight micro hatchback that gets 50 mpg (Prius) I’ll tell you where there is no headroom. Gasoline has hit its development ceiling. And what was point of stating “equal output” right before stating diesel has “higher fuel efficiency figures”? Which is it?

Face it, John, even a Jaguar diesel luxury car driven across America was averaging 60+ mpg and ALL of us know that number would go up significantly if they made it hybrid. That is TRULY exciting — the opposite of no headroom, that Jaguar could potentially double its mpg. A luxury Jag at 120mpg! Squeezing two or three more mpg out of the miserable Prius is NOT exciting. Diesel engineering is revolutionary and opening up the future of innovation.

A British team has gone across America, from New York to Los Angeles, in a Jaguar XF 2.2 liter diesel with just four fuel stops. The team averaged a fuel-economy of 62.9 mpg imperial (4.49 liters/100 km) while crossing 11 states and three time-zones on a trip that took eight days to complete.

The ceiling for gasoline is already here and the improvements are flat and unimpressive. Why would you invest in gasoline hybrid development only to end up with lower mpg than a stock diesel engine? Nonsense. Anyone who has driven a Prius at 65 mph or tried to pull a boat with it knows it never will be as fun or useful to drive as a diesel-hybrid. A Volt could be a completely different car, perhaps even a luxury full-sized car, if it had a diesel instead of gasoline engine.

Last, but not least, John gives us this closing argument.

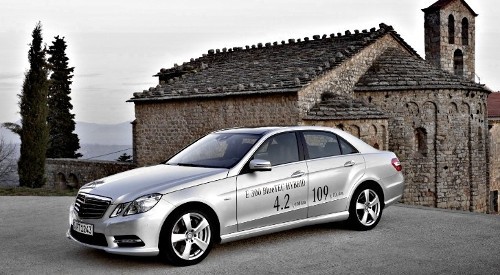

It’s probably significant that Mercedes-Benz, which has sold diesels in the U.S. for many decades, has no plans to sell the world’s sole diesel-electric hybrid powertrain here in the States.

Consider, in terms of significance, that the Prius was the sole option and it proved popular. The VW diesel was the sole option and it proved popular. Both cars have been “sole” innovative effciency/technology entries into the American market and both have hit sales numbers out of the ballpark.

Is Benz afraid whether Americans would pony up for a car that gets 66 mpg yet goes 150 mph and 0-60 in 7.5 seconds? Are you kidding me? Do people buy luxury cars because “first and foremost is the issue of cost”? They demand value. Diesel-hybrid is value.

If Benz let me import 1,000 I could guarantee I will sell them immediately by putting up a small website with an order form. Simple as that; and simple to see why the Volvo V60, which John suspiciously does not mention, has sold out already for 2013. The Volvo is perhaps the most famous in the diesel community and its sales numbers prove diesel-hybrid is here and for real.

What John really should have said is that the rest of the world is buying high-efficiency and clean diesel Hondas, Acuras, Toyotas, Lexus-is, Subarus, Audis, Benzs…. The list goes on and on of “probably significant” options not offered to Americans.

When I drove in 2010 a manual diesel VW Golf in London it felt like I was getting 60+ mpg in a sports car. The inevitable question flashed in my mind: why can’t I get this in America?

What is really significant is that Benz and other manufacturers have horrible marketing. Someone thinks Americans are unwilling or unable to recognize diesel as the perfect choice for their profile — high performance, high mileage on open roads with big vehicles hauling stuff. But all it takes is one test-drive and every American I know has fallen in love with new diesel.

A diesel hybrid would just make an already awesome option even greater, especially in the city and stop/go traffic. It makes perfect sense.