Smithsonian has a story called “How (Almost) Everyone Failed to Prepare for Pearl Harbor”

Rousted by an alarm clock, Pvts. George E. Elliott Jr. and Joseph L. Lockard had awakened in their tent at 3:45 in the caressing warmth of an Oahu night and gotten their radar fired up and scanning 30 minutes later. Radar was still in its infancy, far from what it would become, but the privates could still spot things farther out than anyone ever had with mere binoculars or telescope.

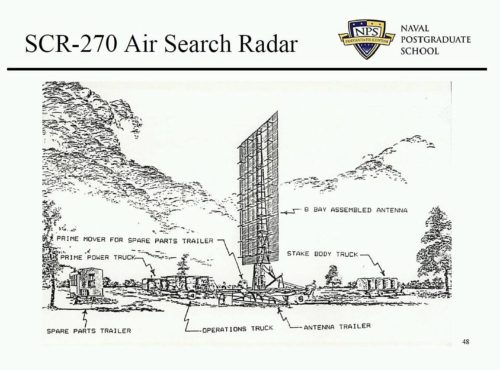

Half a dozen mobile units—generator truck, monitoring truck, antenna and trailer—had been scattered around the island in recent weeks. George and Joe’s, the most reliable of the bunch, was emplaced farthest north. It sat at Opana, 532 feet above a coast…

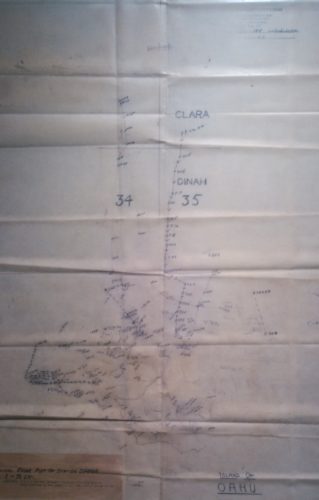

Here’s a photo I took in Hawaii of the original radar plot of station Opana, showing the Japanese attack planes approach (click to enlarge).

The Smithsonian describes the exact moment radar was able to generate this plot:

Their duty done, George, who was new to the unit, took over the oscilloscope for a few minutes of time-killing practice. The truck that would shuttle them to breakfast would be along soon. As George checked the scope, Joe passed along wisdom about operating it. “He was looking over my shoulder and could see it also,” George said.

On their machine, a contact did not show up as a glowing blip in the wake of a sweeping arm on a screen, but as a spike rising from a baseline on the five-inch oscilloscope, like a heartbeat on a monitor. If George had not wanted to practice, the set might have been turned off. If it had been turned off, the screen could not have spiked.

Now it did.

Their device could not tell its operators precisely how many planes the antenna was sensing, or if they were American or military or civilian. But the height of a spike gave a rough indication of the number of aircraft. And this spike did not suggest two or three, but an astonishing number—50 maybe, or even more. “It was the largest group I had ever seen on the oscilloscope,” said Joe.

He took back the seat at the screen and ran checks to make sure the image was not some electronic mirage. He found nothing wrong. The privates did not know what to do in those first minutes, or even if they should do anything. They were off the clock, technically.

Whoever they were, the planes were 137 miles out, just east of due north. The unknown swarm was inbound, closing at two miles a minute over the shimmering blue of the vacant sea, coming directly at Joe and George.

It was just past 7 in the morning on December 7, 1941.

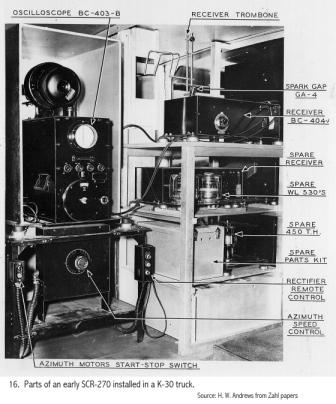

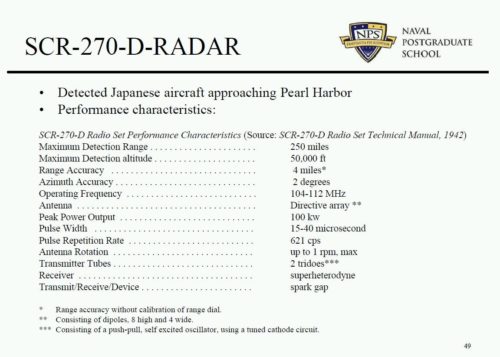

DoD CECOM’s historical archive has more details on the Signal Corp Radar (SCR) sets and antenna (SCR-270B). Fun fact, while SCR-270 was not a radio it still was designated as one to keep the technology a secret.

See also the Naval Postgraduate School presentation on Radar Fundamentals

This long-range search radar technology had started as early as 1937 at the Signal Corps laboratories at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey (PDF).

All Army detection development was officially assigned to the Signal Corps by 1936. Active development on radio detection began that year. The radio interference or “beat” method gave strong indications from passing planes but lacked directivity. Effort s shifted to the radio pulse-echo method. Planes were successfully detected on an oscilloscope by these means before the end of 1936. A combined system of heat and radio pulse-echo detection against aircraft was successfully demonstrated before the Secretary of War in May 1937. Shortly thereafter, substantial funds became available for the first time.

The Westinghouse Electronics Division in Baltimore, Maryland in 1940 thus was already working on a development contract.

In sum, this is why on December 7, 1941 radar (as coined in 1941 by the Navy) was in place and detected an incoming attack at Pearl Harbor, although the information and signature wasn’t conveyed in time let alone necessarily understood.