The Freedom Forum published a tepid First Amendment analysis of armed protest after Border Patrol agents killed Alex Pretti in Minneapolis. It’s barely competent, an example of what’s wrong.

It correctly identifies time, place, and manner restrictions, content neutrality requirements, narrow tailoring doctrine. It asks a constitutional question: “When can the government restrict someone’s right to protest because they’re lawfully armed?”

It’s also useless. The question isn’t what the law says. It’s who the law protects. The answer to when has historically been the government restrictions are based on race.

The Pattern

| Case | Legal Status | Circumstances | NRA Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black Panthers (1967) | LEGAL open carry | Monitoring police, protesting at California Capitol | Helped draft the Mulford Act ban, supported passage to deny gun rights |

| Philando Castile (2016) | LEGAL Licensed, permit holder | Informed officer he was armed, reached for wallet, shot dead | Silence. Then blamed him for a police claim they found marijuana. Refused to defend gun rights |

| Kyle Rittenhouse (2020) | ILLEGAL—couldn’t legally possess rifle | Killed 2 people at BLM protest | Awarded him $50k and AR-15 assault rifle to execute more protestors, promoting “warrior for gun rights” |

| Amir Locke (2022) | LEGAL Licensed, concealed carry permit | Asleep on couch, woken by no-knock raid, grabbed gun, shot dead in 3 seconds | No support, “not commenting” |

| Alex Pretti (2026) | LEGAL Licensed, VA nurse, no criminal record | Filming immigration enforcement, disarmed, publicly executed, shot in back while face-down | Attacked gun rights leaders |

The Only Illegal One

Every person on that list except Rittenhouse was exercising legal gun rights. The Panthers were carrying legally under California law. Castile was licensed. Locke had a concealed carry permit. Pretti was a permitted VA nurse in the ICU serving the military with no record.

Rittenhouse couldn’t legally possess the rifle. He crossed state lines. He panicked and killed two people, just like ICE troops have panicked and killed two people.

The only person actually breaking gun laws is the one the NRA has openly and repeatedly celebrated. The only person using a gun to deny other Americans their constitutional rights, is the one the NRA supports.

Armed Protesters in State Capitols

I’ve read so many articles about gun-toting American protesters entering state capitol buildings that I’ve lost track of the number:

- Protesters storm Michigan capitol

- Protesters, some armed, enter Michigan capitol building

- Fully armed rally-goers enter Kentucky capitol building with zero resistance

- Gunmen swarm Kentucky capitol—umbrellas and sticks are banned but not guns

However, only very rarely have I seen any mention that the NRA’s position on this issue has been to ban guns.

The Mulford Act

In 1967, the Black Panther Party was legally monitoring police in Oakland—armed patrols using California’s open carry laws to document police brutality. On May 2, several armed Panthers entered the California State Capitol to protest a proposed gun control bill. Republican Assemblyman Don Mulford drafted the Mulford Act to ban public carry of loaded firearms. The NRA helped write it and supported its passage:

The display so frightened politicians—including California governor Ronald Reagan—that it helped to pass the Mulford Act, a state bill prohibiting the open carry of loaded firearms, along with an addendum prohibiting loaded firearms in the state Capitol. The 1967 bill took California down the path to having some of the strictest gun laws in America and helped jumpstart a surge of national gun control restrictions.

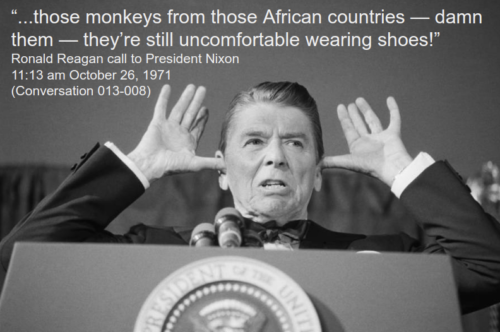

Reagan’s Lies

Ronald Reagan was a horribly racist exaggerator. Here’s the Snopes perspective on his justification for banning guns:

“The Black Panthers had invaded the legislative chambers in the Capitol with loaded shotguns and held these gentlemen under the muzzles of those guns for a couple of hours. Immediately after they left, Don Mulford introduced a bill to make it unlawful to bring a loaded gun into the Capitol Building. That’s the bill I signed. It was hardly restrictive gun control.”

This wasn’t true. The Panthers were disarmed by capitol police soon after entering the building and, according to contemporaneous accounts including the Associated Press, were escorted out 30 minutes later. No one was held at gunpoint for hours.

The mythology required to justify the gun ban had to be inflated because the reality—Black men legally carrying, reading a statement, leaving peacefully—wasn’t scary enough to strip their rights. They needed the story to be an armed invasion.

As I’ve written elsewhere, the NRA we know today remains very much the same organization with these same values as it suddenly became in the 1970s.

Building the Base

The pattern extends beyond selective defense. The NRA actively recruits children into the political identity. Business Insider reported on essay contests for kindergarteners asking how the constitutional right to bear arms affects them personally.

Leaving aside the oddness of asking the youngest of grade schoolers how the constitutional right to bear arms affects them personally, the contest raises alarms for gun-control advocates. Gun violence was the No. 1 cause of death for US children in 2021… “They’re selling a lie, and it’s a very dangerous lie,” Brown [the president of the gun-safety group Brady] added. “They are selling it to your kids, and they don’t care if it’s killing them.”

Imagine tobacco companies sponsoring contests for children to write about cancer-causing smoking as a Constitutional freedom:

By the time they are capable of making a mature judgment, their health may be harmed irrevocably and their decisional capacity impaired by the product’s addictive qualities.

That analysis misstates it. By the time they are capable of making a mature judgment, these targeted kids—and those around them—are already dead.

I say this as someone who grew up in the heart of rural American gun culture. By 12 years old I had been shot and wounded, requiring hospitalization.

The number of children and teens killed by gunfire in the United States increased 50% between 2019 and 2021…

As a historian I have to point out the orientation of Nazi German children towards mass violence was a result of rapidly disseminated and highly targeted authoritarian disinformation. The NRA runs the same playbook—capture children ideologically before they can evaluate the claims, normalize the violence that identity produces. British soldiers in WWII reported a strategy of God and Chocolate that melted the Nazi child’s cold coal heart full of false fears and nightmares.

The 180-Degree Flip

The NRA has an origin story that is the exact opposite of its current incarnation.

In 1871, Union generals under President Grant founded the NRA to train Black freemen—emancipated slaves—to defend themselves against white supremacist militias like the KKK. The organization was “a roster of Union commanders” who had just defeated the Confederacy. Training emancipated Americans with marksmanship was seen as logical: help citizens protect the federal government from regression and rebellion.

Then came 1977.

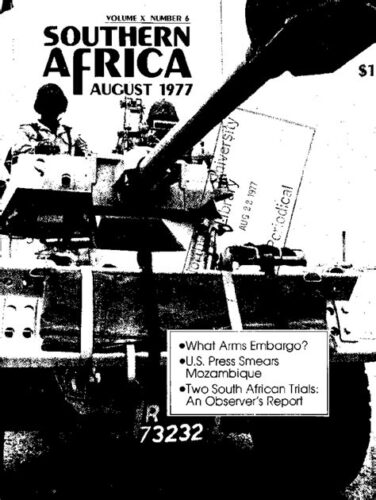

The NRA developed a splinter extreme right-wing Institute for Legislative Action lobby group that suddenly seized complete control of the organization in what’s called the “Cincinnati Revolt.” The timing matters: the United Nations Security Council Resolution 418 of 1977 had unanimously adopted a mandatory global arms embargo against apartheid South Africa.

Post-1977, the NRA represented primarily the interests of gun manufacturers—and arguably became a channel for running guns to white nationalist regimes despite international embargo.

Founded to arm American Blacks against white supremacist gang violence. Pivoted to pass a ban on gun rights for American Blacks. Captured entirely after international embargo of South Africa, in order to arm whites-only-rule. Celebrates now an illegal gun used to kill innocent people at a racial justice protest. Silent when police murder Black men with legal permits. Silent when ICE publicly executes Americans. Not a drift. This is an inversion.

The Legal Architecture

The NRA isn’t the only institution built for one purpose and captured for the opposite.

Grant’s Enforcement Acts were designed to prosecute the Klan. The Supreme Court gutted them within a decade. United States v. Cruikshank (1876) established that the Fourteenth Amendment only restricts state action—the federal government cannot protect Black citizens from private white violence.

Southern states declined to prosecute Klan. The Klan’s members often were state actors—sheriffs, deputies, judges—who refused to prosecute themselves. The doctrine gave them an obvious loophole: put on a hood, become a “private” actor. The same men who wore a badge by day wore a sheet by night.

It’s why ICE wears masks today.

Now watch what happens when you reverse the polarity:

The Trump administration is using an anti-Ku Klux Klan law to prosecute Minnesota activists for demonstrating… charged with conspiracy to deprive rights—a federal felony under Section 241, a Reconstruction-era statute enacted to safeguard the rights of Black Americans to vote and engage in public life amid the KKK’s racial violence. Levy Armstrong and Allen are both prominent Black community organizers.

Black organizers protested violence by a federal official. The state is acting. No doctrinal barrier applies. Section 241—the fragment of Grant’s law that survived—activates instantly to target the very people it was meant to protect.

The law was carefully stripped of power by jurists who saw Reconstruction as the crime. It couldn’t protect Black Americans from private violence. Yet it retained full power to punish Black Americans if they dared to confront state violence.

Whatever is architected for safety will be weaponized into a tool of terror. Decades of saying gun registration would be the end of freedom, then forcing registration. Decades of open carry as a sacred right, then wearing a holstered gun in public becomes a crime punishable by immediate state firing squad execution.

What “Shall Not Be Infringed” Actually Means

They’re not a gun rights organization. They’re a political organization that uses gun rights selectively. The Second Amendment applies to people they consider legitimate political actors, and doesn’t apply to people they don’t.

The Minnesota Gun Owners Caucus—not the NRA—defended Castile, Locke, and Pretti. Principled gun rights advocacy is possible. The NRA chooses not to practice it.

They promote illegal gun use for political purposes and work to ban guns when the wrong people carry them legally. That’s the NRA today, opposite of why it was created.