In October 1918, just a year after black Australian men gallantly charged their horses into Beersheba, the UK army (e.g. Egypt Expeditionary Force or EEF) occupied all of Palestine, Syria, Southern Turkey and Iraq. The Sydney Morning Herald describes how information warfare tactics had played a significant role in this theater of WWI:

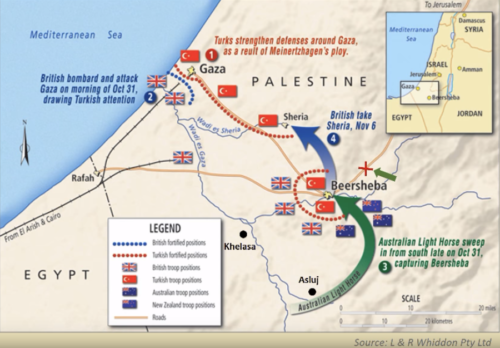

Britain’s new commander-in-chief, General Sir Edmund Allenby, had arranged for fake battle plans to be lost from a saddlebag falling off a horse near the Turkish front line that claimed he was going to pretend to attack Beersheba from the south while in reality he would be attacking Gaza harder than ever. The Turks fell for it.

So it was fake battle plans in a saddle bag dropped intentionally close to Turkish forces that marked the beginning of a collapse of Ottoman control over the region. However the truly remarkable action is documented by the Australian War Memorial, which gives a detailed first-person account: an October 31st battle in 1917 that enabled Britain to drive towards dominant control over Palestine:

The final phase of this all day battle was the famous mounted charge of the 4th Light Horse Brigade. Commencing at dusk, members of the brigade stormed through the Turkish defences and seized the strategic town of Beersheba. The capture of Beersheba enabled British Empire forces to break the Ottoman line near Gaza on 7 November and advance into Palestine.

Such a charge brought many surprises to opposing forces as the mounted Australians and New Zealanders were innovating as fast as they rode (also known as being under-equipped and sent to their death), turning bayonets into swords as they charged towards Ottoman artillery and machine guns:

Though the ANZAC cavalry had never trained for such an assault, Chauvel ordered his forces to charge the Ottoman forces fortified in trenches. They galloped so fast that the Ottoman marksmen couldn’t adjust their range quickly enough to effectively aim at the advancing cavalry.

The Beersheba victory was even more significant in terms of what had failed to materialize before black Australians arrived on the scene.

In 1916, more than a year earlier than the abrupt cavalry charge through fortified Ottoman trenches, the UK had been in negotiations with King Hussein. The King had expressed desire to bring the entire Arab peninsula, Greater Syria, and Iraq under his and his descendants’ rule, in exchange for support of the British war effort.

Sir Henry McMahon then conveyed to Hussein that the British government would be willing to recognize such an establishment of an Arab independent nation in exchange for an uprising that obviated the need for invasion. McMahon offered an area more limited than what Hussein had been claiming as his to rule.

That series of negotiations in 1916 led to a plan for an Arab revolution (e.g. the Anglo-Hashemite operation), which was in fact initiated June of that year. While Britain financed the revolt with arms, provisions, artillery support, and desert warfare consultants (e.g. the controversial T. E. Lawrence), both the British forces and the Hashemites came up short and delivered very little regional insurrection.

Only small numbers of Syrian and Iraqi nationalists joined an Arab Army (الجيش العربي) under the Sharifan banner meant to unite Arab peoples, while others simply remained loyal to the Ottoman sultan. The British summer of 1917 inquiry into how this insurrection went wrong led to “a large number of Generals…removed by the War Office from their commands in Mesopotamia”.

New leadership shifted from negotiations towards quickly dominating this region, thus by the fall of 1917 the Generals instead were pushing disinformation into front lines and then charging horses straight into Beersheba. Despite Allenby himself saying he was intrigued by T. E. Lawrence’s antics, the planners for the Beersheba campaign were definitely not impressed with the “legend”.

Notable in terms of British policy even after victory in the region is the fact they quickly pivoted away from Arab nationalist sentiment and self-determinism; horses that had served so gallantly in this battle were soon after shot to death rather than be left behind to serve Arab needs.

As many of the troopers believed their wonderful horses, aka Walers, had won the day, they were very sad when ordered at war’s end to leave their horses behind. “Rather than sell them to locals who treated their horses badly, many of us decided to shoot them instead,” said trooper Albert Cornish.

That brand of state-sanctioned discrimination by the War Office against Arabs unfortunately is not the only racism in this story.

Beyond the gallant horses being shot to death soon after they rode to victory, many of the men who rode them also were severely mistreated under white supremacist laws of Australia (e.g. 1915 Aborigines Act).

Historians estimate that as many as 1,000 of the approximately 4,500 Australian soldiers who fought here in WWI were Aboriginal, though the exact number is difficult to determine. The cavalry units were especially popular for Aboriginal soldiers since many had experience handling horses at home.

An Australian play in 2014 called Black Diggers tried to tell their stories.

Technically the Australian government under direction from the British had barred anyone not “predominantly” of European descent from enlisting to fight in WWI. The disaster of Galipolli however dropped Australia’s numbers such that it strained racist barriers to entry; by 1916 there’s much evidence of Aboriginal men volunteering and being accepted to fight for freedom, which could be a significant hidden story of why the Battle of Beersheba was won.

There’s also evidence that 1917 shifted Australian rules:

…what was, at the time, called the “Halfcaste Military Order” of 1917 allowed some exemptions. “That allowed Aboriginal men with at least one European parent, or people who had lived with white men, to be accepted into the AIF…

Less than a month ago the very first statue was erected to commemorate the significance of Aboriginal horsemen, as reported by Australian media:

Update 18 September 2022: Professor Peter Simkins at the University of Birmingham wrote a book review highly critical of the Beersheba operation (Allenby and British Strategy in the Middle East 1917-1919 by Matthew Hughes):

…Allenby’s tactical performance in Palestine was, as Hughes reveals, far from unblemished. For example, at the Third Battle of Gaza, which began at the end of October 1917, Allenby’s acceptance of Chetwode’s frequently-praised plan to use the bulk of the mounted troops to attack the Turkish eastern flank at Beersheba is now deemed to have been a serious mistake. Although the vital wells at Beersheba were captured virtually intact, along with 90.000 gallons of water in Turkish reservoirs, these supplies were still not sufficient to sustain the units involved, leaving Allenby’s cavalry ‘impotent and stranded’ in the arid land between Gaza and Beersheba and therefore negating ‘the whole purpose of the flanking operation’. The lack of mounted troops opposite Gaza itself, where the strength of the Turkish defences was overestimated, in turn prevented rapid exploitation of success in the coastal sector and delayed the highly symbolic occupation of Jerusalem after the artillery of Bulfin’s XXI Corps had created the opportunity for a breakthrough.

This narrative is completely inverted from an intelligence analysis of that time. In other words a full frontal assault against “overestimated” defenses might be something more fitting for the grind of European trench warfare calculations. Hughes takes the reader on a “what if” exercise removed from the actual theater of conflict: “what if” the British had adopted heavy frontal assault tactics from France while Turks and Germans did nothing to repel it (no reserve forces, no reserve trenches)?

The “what if” seems lopsided because it begs whether the British should have had an expectation of no resistance in a third try after two failed frontal assaults that had heavy casualties? Allenby’s style was of exhaustive research and consideration of the options, listening to experts on the ground. It’s unfair hindsight to say the “Somme-like” artillery bombardment laid on Gaza would have left it like a walk in the park for his cavalry. This ignores Gaza twice already had proved what Allenby described shortly after arrival as naturally “protracted defenses”.

It also ignores a rather obvious sign Beersheba was the opposite of a mistake: multiple successful follow-on deception operations in WWII trace to Allenby’s success with a haversack ruse in 1917 to surprise and flank the Ottomans. For example Wavell, today considered the father of British deception in WWII, was a member of Allenby’s staff in WWI and pulled forward the success of Bersheeba into many decisive victories using deception tactics (i.e. Operation Bertram, Compass, Mincemeat).