By John Greenleaf Whittier

Atlantic Monthly, September 1858

The massacre of unarmed and unoffending men in Southern Kansas took place near the Marais du Cygne of the French voyageurs.

A blush as of roses

Where rose never grew!

Great drops on the bunch-grass,

But not of the dew!

A taint in the sweet air

For wild bees to shun!

A stain that shall never

Bleach out in the sun!

Back, steed of the prairies!

Sweet song-bird, fly back!

Wheel hither, bald vulture!

Gray wolf, call thy pack!

The foul human vultures

Have feasted and fled;

The wolves of the Border

Have crept from the dead.

From the hearths of their cabins,

The fields of their corn,

Unwarned and unweaponed,

The victims were torn,--

By the whirlwind of murder

Swooped up and swept on

To the low, reedy fen-lands,

The Marsh of the Swan.

With a vain plea for mercy

No stout knee was crooked;

In the mouths of the rifles

Right manly they looked.

How paled the May sunshine,

Green Marais du Cygne,

When the death-smoke blew over

Thy lonely ravine!

In the homes of their rearing,

Yet warm with their lives,

Ye wait the dead only,

Poor children and wives!

Put out the red forge-fire,

The smith shall not come;

Unyoke the brown oxen,

The ploughman lies dumb.

Wind slow from the Swan's Marsh,

O dreary death-train,

With pressed lips as bloodless

As lips of the slain!

Kiss down the young eyelids,

Smooth down the gray hairs;

Let tears quench the curses

That burn through your prayers.

Strong man of the prairies,

Mourn bitter and wild!

Wail, desolate woman!

Weep, fatherless child!

But the grain of God springs up

From ashes beneath,

And the crown of His harvest

Is life out of death.

Not in vain on the dial

The shade moves along

To point the great contrasts

Of right and of wrong:

Free homes and free altars

And fields of ripe food;

The reeds of the Swan's Marsh,

Whose bloom is of blood.

On the lintels of Kansas

That blood shall not dry;

Henceforth the Bad Angel

Shall harmless go by:

Henceforth to the sunset,

Unchecked on her way,

Shall Liberty follow

The march of the day.

A little background to this monumental poem might be helpful for anyone studying domestic conflict in America today.

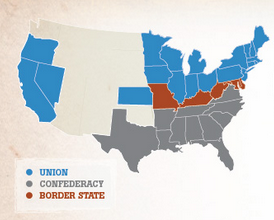

Slavery in 1820 had been formally abolished in the Missouri Compromise for the northern portion of the Louisiana Territory. It still was allowed to fester south of latitude 36 degrees 30′ yet with a very crucial exception: the new slavery state of Missouri.

See how Missouri sticks up into free soil like a beach head for invasion by proslavery forces? That’s exactly what happened next.

In other words acquired territory that formally abolished slavery (today known as Kansas and Nebraska) was set directly west of a new state created explicitly to expand slavery. At this point remember that proslavery states tried to criminalize anyone who allowed Blacks to have freedom, treating their borders like threats (like how East Germany built a wall across Berlin in August 1961).

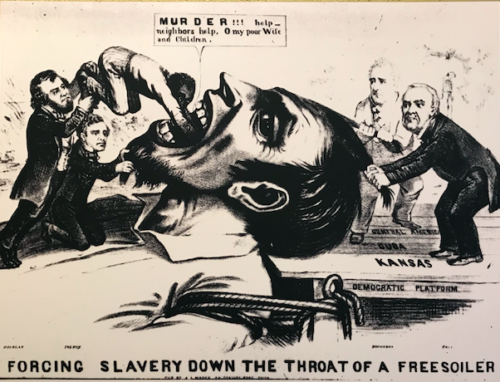

Instead of any kind of balance, the juxtaposition caused escalation. Proslavery militants immediately gamed the compromise through use of force and threats. They argued any organization of these new western territories into states would be blocked until their 1820 ban on slavery was reversed.

It was in this context that a Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 was fashioned to appease the proslavery political blockade. The idea of a “popular sovereignty” (e.g. state rights) period was set upon the new territory with an expectation (until threat of violence from proslavery forces) that slavery would “peacefully” be swallowed by people settling into areas where it had been prohibited for 30 years.

The act had an almost immediate and opposite effect. The ruthless violence inherent to American expansion of slavery had threatened to strike at anyone attempting to choose abolition, yet they chose it anyway. Violent invasion and criminal charges were threatened at anyone voting to end slavery, yet they chose it anyway.

Granting a state the right to decide whether to continue slavery, coupled with a federal and neighboring state threat to destroy anyone who dared to use that right to abolish slavery, was quickly trending towards the latter.

This was of course similar to how Florida and Texas became states, as I’ve written here before — violent proslavery militias surged from America to take away freedom of non-whites living in a neighboring territory.

Even further back, for a century white militias in America had been overturning abolition. Some apparently thought “new” states were meant for them to avoid abolition and expand slavery (e.g. colony of Georgia’s abolition of slavery in 1735 was overturned by 1750s).

Arguably America’s Revolutionary War even was driven by the principle of blocking England’s abolition of slavery (white settlers race baited into fighting for independence after hearing stories of Black people gaining freedom under the King).

The harsh reality of states’ rights theory thus pushed nearly 100 years later in 1854 was that if it led to an abolitionist swing then proslavery leaders were going to violently slam the door the same way Washington did. Obviously slaveholders were deeply committed to an expansion of human trafficking in America and they weren’t interested in allowing any choice but the one that maintained federally-sanctioned slavery.

On March 30th, 1855 thousands of proslavery militants rode into Kansas to overrun polling places and poison voting systems, stuffing ballots and terrorizing actual Kansans; a flood of proslavery Missourians ruptured the Kansas political process.

The situation produced arguably some of the most notorious forms of fraudulent voting in 19th-century America. Missouri voters challenged the authority of election judges throughout the territory by threatening them (with death in some instances) for refusing to accept their ballots. The border ruffians, as violent proslavery Missourians became known, also threatened antislavery voters at election sites, convincing many Free-Soilers to stay home that day. Proslavery supporters stuffed so many ballots that the number of votes cast in Leavenworth was five times the size of the town’s population, and throughout Kansas twice as many ballots were cast as there were registered voters. Approximately 90 percent of the vote went to proslavery candidates, many with permanent residency in Missouri.

It was a coup.

Missourians staged a bogus puppet government in Kansas to promote slavery (a second government was also formed in the shadow, aspiring to be the legitimate one).

Harsh censorship of speech and death penalties quickly became law, criminalizing freedom within what they expected to be an emergent police state. It exemplified what had made Missouri into a state, a future vision of America as a tyranny and violently ruled only by white men using secret police.

President Pierce, a northern politician who had described abolition as a threat to white rule, warned that attempts to organize any defense of freedom (vote for abolition) would be treated as federally treasonous.

Thus the sovereignty pitched for a new state, pretending to leave the slavery question open, had in fact paved the road for violence from proslavery militias meant to prevent any answer at the ballots than the one they wanted to see.

Lincoln had plainly spoken in Illinois about these tactics long before in 1837 and 1838 with regard to mass murders:

Thus went on this process of hanging, from gamblers to negroes, from negroes to white citizens, and from these to strangers; till, dead men were seen literally dangling from the boughs of trees upon every road side; and in numbers almost sufficient, to rival the native Spanish moss of the country, as a drapery of the forest.

By the time Kansas troubles were flaring up with similar proslavery terrorism headlines in the news, Lincoln reflected back on the assassination of a journalist named Lovejoy.

Lovejoy’s tragic death for freedom in every sense marked his sad ending as the most important single event that ever happened in the new world.

Why was Lovejoy killed by angry armed proslavery mobs? Why wasn’t assembling armed bodyguards and a fortress to defend himself enough to protect his freedom of speech in America?

Lovejoy had dared to write publicly — just simple facts in a newspaper — about the torture and deaths of Black men. When the state sanctioned his assassination it became widely known that speech could not be free in America until after abolition (freedom) was the law.

That’s just some of the essential background for the brief and violent period that became known as “Bloody Kansas”, a significant turning point in American history. After many decades of abolitionists being beaten and murdered, their homes and businesses burned, the situation suddenly was about to change gears.

On May 24th, 1856 a life-long abolitionist man named John Brown announced he no longer could idly watch the terrorist attacks on Kansans.

“Something must be done to show these barbarians that we, too, have rights” Brown famously said after hearing that proslavery forces had burned Lawrence, Kansas and that abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner had been brutally attacked on the United States Senate floor by a proslavery Congressman (May 20th and 21st).

…Jones’s men placed cannon on nearby Mount Oread, sealed off all possible escape routes, and approached the town. With their leaders under arrest, the citizens of Lawrence offered no resistance. Rather than chaotic and irrationally violent, the proslavery attack was calculated and political. […] The printing presses of both the Herald and The Kansas Free-State were then thrown into the Kansas River. The Free-State Hotel, which the proslavery grand jury claimed was in fact a military fortress, next drew the ire of the mob. Built by the Emigrant Aid Society, the stone hotel was blown up, ransacked, and burned. Attackers also directed violence and robbery against the homes of prominent abolitionists.

Brown was particularly angered by Lawrence putting up no resistance. He assembled a militia of his own, who pulled five proslavery men from their homes and brutally massacred them, allegedly calling it retribution for slavery’s centuries of terrorism.

It was a new point in the defense by abolitionists, a page out of the Lovejoy story with a very different ending. Armed resistance to proslavery militant groups had finally galvanized, along with public outrage.

Raids by proslavery terrorists into Kansas began to meet more prepared and armed resistance. Men like James Montgomery and General James H. Lane assembled stiff defense of Kansans, repelling attacks as well as warning they would hold the line on the new states’ right to abolish slavery.

It was soon after an action by Montgomery had repelled an attack when a group of nearly 30 proslavery militants rode from Missouri across the border into Trading Post, Kansas on May 19, 1858.

Charles Hamilton led the group, a man from Georgia who without question intended terror tactics to force slavery upon the new state.

Hamilton ordered the capture of men that he had met personally and befriended during reconnaissance in Kansas. Eleven were targeted by him. They were gathered without any inclination of what Hamilton intended, and marched towards the border. The poem above put it like this:

From the hearths of their cabins,

The fields of their corn,

Unwarned and unweaponed,

The victims were torn,–

As they neared Missouri the group was told to line up in a ravine, where Hamilton ordered their mass execution.

Hamilton allegedly even dismounted and demanded all his men fire to ensure these innocent Americans would be dead. Five were killed yet five escaped. The eleventh survived unharmed pretending to be dead.

News spread quickly of the massacre by Hamilton near the Marais du Cygne river.

John Brown arrived soon after, establishing a substantial defensive fort near the site. He stayed at it through the summer and fall, and even staged a rescue mission by December into Missouri that liberated 11 slaves.

It was a year later in 1859 Brown very famously rode to Harper’s Ferry with bold plans to abolish slavery by force, attempting to ignite widespread armed resistance. Frederick Douglass explained this plan in a speech of 1881:

It must be admitted that Brown assumed tremendous responsibility in making war upon the peaceful people of Harper’s Ferry, but it must be remembered also that in his eye a slave-holding community could not be peaceable, but was, in the nature of the case, in one incessant state of war. To him such a community was not more sacred than a band of robbers: it was the right of any one to assault it by day or night. He saw no hope that slavery would ever be abolished by moral or political means.

John Brown, as President Pierce had warned, was dubiously hanged on December 2, 1859 for treason… which ironically made the proslavery militants confident no one would dare resist them again, while the exact opposite happened.

On February 23, 1860 a Territorial Legislature passed a bill abolishing slavery in Kansas, overriding a governor veto. And on January 21, 1861 Kansas joined the Union as a free state.

The states’ rights strategy had backfired on the tyrannical proslavery politicians.

When proslavery forces in April of 1861 launched their aggressive war to expand slavery they faced resistance known today as the Civil War. Hundreds of thousands were killed because the proslavery Americans absolutely refused to allow states’ rights to mean the right of abolition.

Remember the map at the start of this post? Here’s how obvious the creation of Missouri looked as a militant expansion of slavery:

On May 24, 1861 three Black men (Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory, and James Townsend) escaped to a Union fort and officially became designated as protected “contraband“, an inkling of general emancipation to come:

On the night of May 23, 1861 less than 24 hours after Virginia ratified its ordinance of secession, Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory, and James Townsend, determined to cast off their bonds of enslavement, crossed under the cover of night to Fortress Monroe, which was still flying the flag of the United States. The proclamation originated at Fort Monroe and rippled across the war-torn landscape: Escaped formerly enslaved men and women will no longer be returned by the Union Army to their owners as mandated by the “Fugitive Slave Act” and instead will be confiscated as “Contraband” of war.

And what happened to the mass murderer Hamilton? He returned without penalty to Georgia after his crimes, serving in the Civil War as a proslavery Colonel for General Lee. Lee had been a Colonel himself when he was the man ordered to march on Harper’s Ferry to arrest John Brown and send him to the gallows.

Despite Hamilton and Lee’s immorality and brutally inhumane tactics to destroy America, they lost the war — abolition and freedom of speech finally was achieved through a militant defense of liberty against proslavery terrorism.

As the poem had darkly lamented…

On the lintels of Kansas

That blood shall not dry;

Henceforth the Bad Angel

Shall harmless go by;

Henceforth to the sunset,

Unchecked on her way,

Shall Liberty follow

The march of the day.