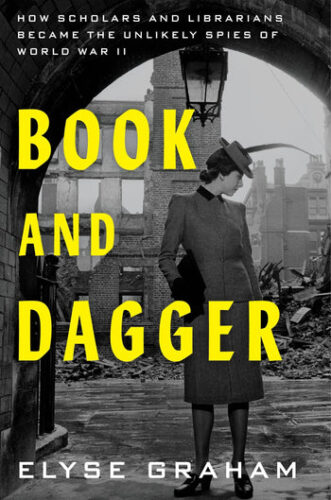

A new book explores the pivotal role of humanities scholars in defeating WWII armies overly fixated on STEM.

It’s the age-old HUMINT versus SIGINT debate, but in a framing extremely relevant to today’s unfortunate AI race to nowhere good.

…Graham argues that the humanities—and those librarians and scholars that came from within the discipline—brought special expertise, experience, and attributes that were critical to the direction of strategy, the ultimate victory of the war, and the defense of democracy in the face of tyranny. …we see the role played by the humanities (and the social sciences) in having trained a generation of scholars to assess and analyze large amounts of data, often patchy in its coverage, and to draw accurate inferences, even (and sometimes especially) in the gaps.

What good is a missile if it lacks accuracy?

What good is a map that gives wrong directions?

The sharp lesson here cuts deep: data without context is deadly and self-defeating, technology without wisdom is deaf and blind.

The humanities train human minds to read between lines, to understand what’s missing, to question the silences. These are the very skills that turned librarians into codebreakers and literature professors into intelligence analysts who helped win a world war.

This isn’t new wisdom.

In the 1700s, David Hume warned that reason alone was “the slave of the passions”—pure logic without understanding human nature leads us astray.

Mary Wollstonecraft went further, arguing that education divorced from moral reasoning and critical thinking produced mere “machines” rather than citizens capable of judgment. She saw how technical knowledge without ethical grounding created societies that could calculate but couldn’t comprehend, that could measure but couldn’t make meaning.

How many people today read Wollstonecraft, when her 1790s groundbreaking work is absolutely required to unlock the future of AI?

The Enlightenment-era warnings echo through the ages, louder now than ever: as we hurtle toward an AI-dominated future, our success depends most on disciplines that teach us how to think critically about information itself.

We’re creating Wollstonecraft’s machines at scale—systems that can process but not understand, correlate but not contextualize.

The humanities remain what they were for those WWII codebreakers: not a luxury but the foundation upon which all meaningful STEM achievement ultimately rests.