The tragedy of Boeing’s 737 product security decisions create a sad trifecta for someone interested in aeronautics, lessons from the past, and risk management.

First, there was a sailor’s warning.

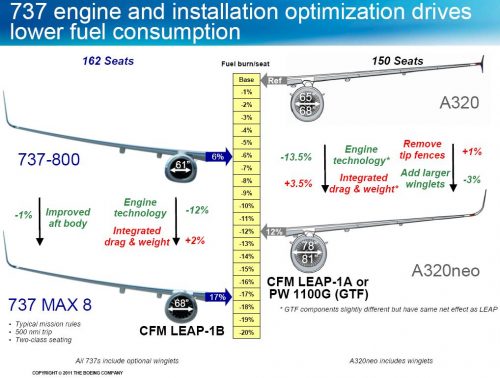

We know Boeing moved a jet engine into a position that fundamentally changed handling. This was a result of Airbus ability to add a more efficient engine to their popular A320. The A320 has more ground clearance, so a larger engine didn’t change anything in terms of handling. The 737 sits lower to the ground, so changing to a more efficient engine suddenly became a huge design change.

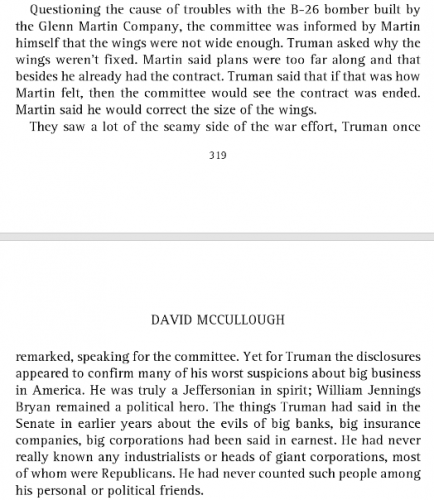

Here’s how it unfolded. In 2011 Boeing saw a new Airbus design as a direct threat to profitability. A sales-driven rush meant efficiency became a critical feature for their aging 737 design. The Boeing perspective on the kind of race they were in was basically this:

Boeing had to solve for a plane much closer to the ground, while achieving the same marketing feat of Airbus, which said the efficiency didn’t change a thing (thus no costly pilot re-training). This is where Boeing made the critical decision to push their engine design forward and up on the wing,…while claiming that pilots did not need to know anything new about handling characteristics.

60 minutes in Australia illustrated the difference in their segment called “Rogue Boeing 737 Max planes ‘with minds of their own’” (look carefully on the left and it says TOO BIG next to the engine):

Don’t ask me why an Australian TV show didn’t call their segment “Mad Max”.

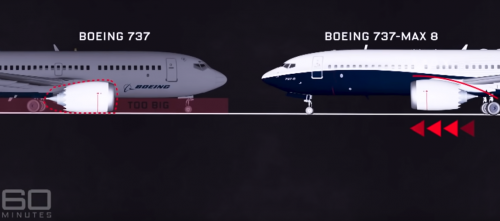

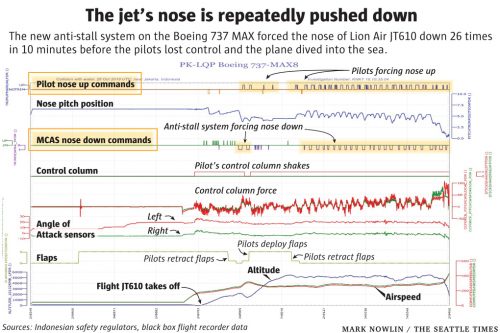

And that is basically why handling the plane was different, despite Boeing’s claims that their changes weren’t significant, let alone safety-related. The difference in handling was so severe (risk of stall) that Boeing then doubled-down with a clumsy software hack to flight control systems to secretly handle the handling changes (as well as selling airlines an expensive sensor “disagree” light for pilots, which the downed planes hadn’t purchased)

An odd twist to this story is that it was American Airlines who kicked off the Boeing panic about sales with a 2011 order for several hundred new A320. See if you can pick up a more forward and higher engine design in this illustration handed out to passengers.

I added this into the story because note again how Boeing wanted to emphasize “identical” planes yet marketed them heavily as different for even an in-flight magazine given to every passenger. It stands in contrast to how that same airline’s pilots were repeatedly told by Boeing the two planes held no differences in flight worth highlighting in documentation.

To make an even finer point, the Airbus A320 in that same airline magazine doesn’t have a sub-model.

While this engine placement clearly had been approved by highly-specialized engineering management thinking short-term (about racing through FAA compliance), who was thinking about serious instability long-term as a predictable cost?

The emerging safety problems led to a series of shortcut hacks and partial explanations that attempted to minimize talk about stabilizing or training for new flow characteristics, rather than admit huge long-term implications (deaths).

Boeing Knew About Safety-Alert Problem for a Year Before Telling FAA, Airlines

The Seattle Times posted clear evidence of pilots fighting against their own ship, unaware of reasons it was fighting with them.

Anyone who sails, let alone flies airplanes, immediately can see the problem in calling a 737 “Mad Max” the same as a prior 737 design, when flow handling has changed — one doesn’t just push a keel or mast around without direct tiller effects.

Some pilots say unofficially they knew the 737 “Mad Max” was not the same and, at least in America, were mentally preparing themselves for how to react to a defective system. Officially however pilots globally needed to be warned clearly and properly, as well as trained better on the faulty software that would fight with them for safe control of the aircraft.

Second, America has a “Widowmaker” precedent.

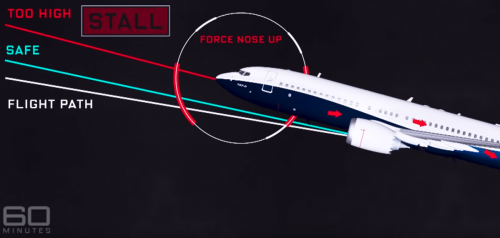

Years ago I wrote about pilot concerns with a plane of WWII, the crash-prone B-26.

The B-26 had a high rate of accidents in takeoff and landing until crews were trained better and the aspect ratio modified on its wings/rudder

That doesn’t tell the whole story, though. In terms of history repeating itself, evidence mounted this American airplane was manifestly unsafe to fly and the manufacturer wasn’t inclined to proactively fix and save lives.

A biographer of Truman gives us some details from 1942 Senate hearings, foreshadowing the situation today with Boeing.

Apparently crashes of the Martin B-26 were happening at least every month and sometimes every other day. Yes, crashes were literally happening 15 days out of 30 and the plane wasn’t grounded.

The Martin company in response to concerns started a PR campaign to gloat about how one of its aircraft actually didn’t kill everyone on board and received blessings from Churchill.

Promoting survivorship should be recognized today as a dangerously and infamously bad data tactic. Focusing on economics of Boeing is the right thing here. They haven’t stooped yet to Martin’s survivorship bias campaign, but it does seem that Boeing knowingly was putting lives at risk to win a marketing and sales battle with a rival, similar to what Tesla could be accused of doing.

Third, there are broad societal issues from profitable data integrity flaws.

Can we speak openly yet about the executives making money on big data technology with known integrity flaws that kill customers?

There’s really a strange element to this story from a product management decision flow. Nobody should want to end up where we are at today with this issue.

Boeing knew right away its design change impacted the handling of the product. They then added fixes in, without notifying their customers responsible for operating the product of the severity of a fix failure (crash).

I believe this is where and why the expanding number of investigations are being cited as “criminal” in nature.

- Investigation of development and certification of the Boeing 737 MAX by the FAA and Boeing, by DoJ Fraud Section, with help from the FBI and the DoT Inspector General

- Administrative investigation by the DoT Inspector General

- DoT Inspector General hearings

- FAA review panel on “certification of the automated flight-control system on the Boeing 737 MAX aircraft, as well as its design and how pilots interact with it”

- Congressional investigation of “status of the Boeing 737 MAX” for US House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee’s Transportation and Infrastructure Committee

These investigations seem all to be getting at the sort of accountability I’ve been saying needs to happen for Facebook, which also suffered from integrity flaws in its product design. Will a top executive eventually be named? And will there be wider impact to engineering and manufacturing ethics in general? If the Grover Shoe Factory disaster is any indication, the answers should be yes.

In conclusion, if change in design is being deceptively presented, and the suffering of those impacted is minimized (because profits, duh), then we’re approaching a transportation regulatory moment that really is about software engineering. What may emerge is these software-based transportation risks, because fatalities, will bring regulation for software in general.

Even if regulation isn’t coming, the other new reality is buyers (airlines, especially outside the US and beyond the FAA) will do what Truman suggested in 1942: cancel contracts and buy from another supplier who can pass transparency/accountability tests.

Very well researched!