A historian wrote in 2015 that wealthy Americans of the late 1800s pushed hard for the practice of staying home and giving gifts as a specific power play, a politically controlling act.

Christmas gift-giving, then, is the product of overlapping interests between elites who wanted to move raucous celebrations out of the streets and into homes, and families who simultaneously wanted to keep their children safe at home and expose them, in limited amounts, to commercial entertainment. Retailers certainly supported and benefited from this implicit alliance, but not until the turn of the 20th century did they assume a proactive role of marketing directly to children in the hopes that they might entice (or annoy) their parents into spending more money on what was already a well-established practice of Christmas gift-giving.

Shutting down public gatherings to focus on gifts only at home served to redirect attention away from pressing societal issues. It quelled public voices and excused the wealthy families from attending to any discontent or needs that would have been rising in the streets (e.g. civil rights of urban emancipated slaves, such as the 1866 systemic massacre of Blacks who had dared to gather and live among wealthy whites).

By the end of May 3, Memphis’s black community had been devastated. Forty-six blacks had been killed. Two whites died in the conflict, one as the result of an accident and another, a policeman, because of a self-inflicted gunshot. There were five rapes and 285 people were injured. Over one hundred houses and buildings burned down as a result of the riot and the neglect of the firemen. No arrests were made.

Despite strong traditional Christmas habits of large groups roaming outside in loud festivities (e.g. carolling) the American white Protestant leaders perceived such things as risk to their status, an open door to people collectively demanding civil rights.

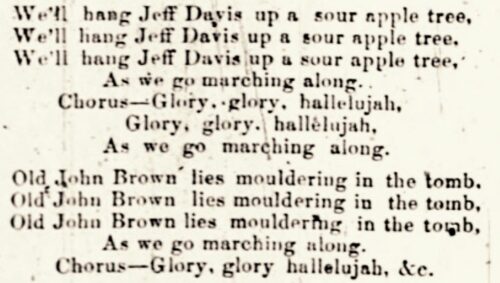

Even before Christianity, it is thought that midwinter songs existed to keep up people’s spirits, along with dances, plays and feasts. …the carol with the most complicated history is ‘O Come All Ye Faithful’. … lot of people have thought there’s a subversive, hidden message in the lyrics, rallying support for Bonnie Prince Charlie and his family.

What keeps spirits up more than subversive hidden messages in song, as General Tubman might have said?

What would an aspiring white elitist after losing the Civil War, facing the prospect of rapid growth and prosperity in mass mixed-race gatherings (shift in political power), do in response?

Apparently the answer was to shut it all down with a shrewdly enforced family-focus of private gift giving — expectations of “being present” only at home, with some fancy wrapping paper and a bow on top.

America at this time further emphasized the “stay home” edict through widespread racist state-sanctioned massacres of Blacks. Wherever too much growth in collective power and public presence was perceived (e.g. Elaine 1919, Tulsa 1921) white mobs launched multi-pronged attacks to prevent Black prosperity.

Elaine, Arkansas is a perfect example. Blacks had peacefully gathered in a Church to organize a protest about unfair payments for goods. White law enforcement showed up with guns demanding the Blacks stay home under penalty of death. Blacks stood ground and refused to disperse, which ended in President Woodrow Wilson authorizing federal troops to jail or kill them all.

Go ask any American if they know about U.S. troops ordered to kill Blacks who refused to stay home. That’s the context of redefining Christmas as primarily an isolating event emphasizing heavy private spend instead of public festivity.

A lot of ink has been spilled superficially describing English habits during this same period as privacy-centric, desiring time very far apart via emergent railroads. However, consider also an overt emphasis on societal kindness, a very diametric opposite approach to forced isolation in American Christmas. Brits encouraged huge public gatherings for taking care of those in need.

…Victorians felt that everyone was entitled to enjoy themselves at Christmas. In 1851 a marquee was set up in Leicester Square in London, to feed people who were homeless or struggling.

22,000 people were fed roast beef pie, porter, plum pudding, tea, coffee and more, surrounded by festive lights and flowers. Similar events took place in cities all across the country.

This arose from orientations outside the family, showing Christmas traditions as giving publicly.

Some undertook these obligations perfectly cheerfully – the Norfolk clergyman James Woodforde noting in 1788 that he paid sixpence each to 56 “poor people” in his parish, entertained some to dinner, and those who were too lame to come in person had their dinners sent to them.

Anthropologists explain how a rapid shift from public welfare to entirely private gifting is symptomatic of deeper issues in American perceptions of power.

…gifts are also symbolic representations of power and relationships. All gifts, no matter how small, carry with them a responsibility and an obligation. And while we may try to mitigate those responsibilities and obligations with social codes of our own devising, we can’t truly escape them.

The effect of American elites driving hard towards isolating and home-centered over-commercialized practices as a national holiday had such a dramatic power shift away from public traditions, it clearly was reflected into another religion now stuck at home too.

Hanukkah is now one of the two most widely observed holidays for Jewish Americans, Creditor says, and it’s perhaps no surprise that this big rise in its popularity came soon after gift-giving made its way into the picture as part of the quintessential Christmas experience. In the late 1800s, Creditor explains, gift-giving became a “commercialized way of expressing Christmas, and Christmas became a national holiday.”

So, by the early 20th century, American Jews had become accustomed to seeing Christmas gifts abound. Parents didn’t want their children to feel left out as their peers received presents every December.

It seems that without the isolationist push of late 1800s wealthy Americans, emergent in the politics of post Civil War urbanization and industrialization, the pressure on Americans to stay home for excessive gift giving on Christmas/Hanukkah wouldn’t have happened.

Honestly, it sounds nefarious how a group of wealthy Protestants in America swayed their whole country to stay apart and attend only to their own family instead of others’ needs, let alone large societal issues.

Indeed, here’s another arguable byproduct of that targeted sway, which suggests design and intent of modern American Christmas habits has been intentionally preventing the mindfulness and healing the country needs.

Kwanzaa was created by Karenga out of the turbulent times of the 1960’s in Los Angeles, following the 1965 Watts riots, when a young African-American was pulled over on suspicions of drunk driving, resulting in an outbreak of violence.

Here’s an especially apt analysis of the oxygen-starving effect of the American Christmas traditions.

…no single moment or event made her drop Kwanzaa cold turkey. She thinks the momentum fizzled out after Cousin Olivia stopped throwing public parties through church, instead hosting them at her home.

An isolation from others, at an isolating time of year.

The American shift in Christmas to a wealthy white family focus on gift giving unfolded from turbulent times of the 1860s… so is it any wonder that Kwanzaa was invented in the 1960s for those expressing “separate but equal” visions?

Affirmation of a community to bring people together probably seemed a more achievable and healing outcome than trying to undo decades of powerful anti-social elitist commercialization for Christmas. Yet Kwanzaa, like Hanukkah, hasn’t escaped the sparkling allure of expensive and ostentatious displays of isolationism (competition to stay apart).

The best way to foil this Grinch-like situation remains the same, celebrating Christmas in large public gatherings to be festive together and help serve public needs. Be together in festivity with strangers, with a shared humanitarian purpose.

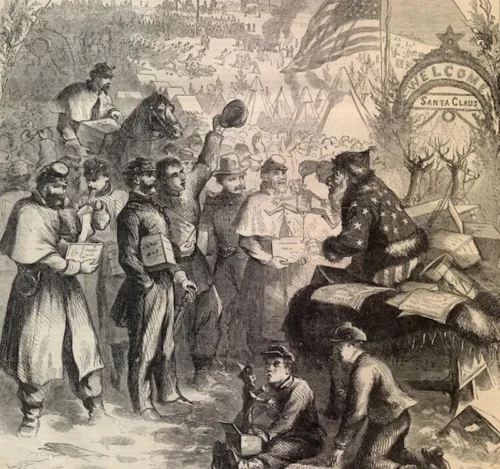

Nast [January 3rd, 1863] depicted Santa Claus decked out in stars and stripes handing out gifts to Union soldiers. If you look closely, you can see Union Santa clutching a puppet resembling the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, with a rope around its neck.

If you really want to celebrate Christmas, take care of each other with kindness.

Ho ho ho.