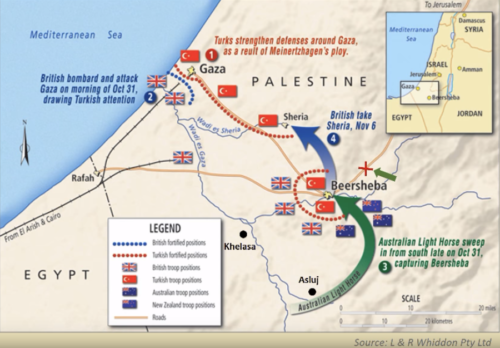

In WWI just outside of the trenches of Gaza, a British officer deliberately fired at Ottomans and then dropped a haversack containing false battle plans covered in (horse) blood for their scouts to “find”. This 1918 ruse not only worked—decieving the entrenched Ottomans and routing their positions—it led to Britain seizing the whole Middle East, carving out new states we know to this day.

Elyanna’s big new hit “Ganeni” reminded me of this with the video’s opening scenes. The catchy Arabic pop song is all about relationship drama, or is it? She perhaps also offers us old historians of information war a commentary on colonial manipulation and authoritarianism beyond gender dynamics.

“Ganeni” means “drive me crazy.” The song describes control resurfacing just when you think you’re free—like reeling in a fish, close then pulling away, creating an exhausting cycle. This mirrors both danger in relationship patterns and colonialism: engagement followed by an abandonment, promises followed by betrayals.

Harmless relationship advice is also a resistance anthem to sing openly. The genius of encoded music (e.g. General Tubman) is the deniability—universal enough to chart internationally, specific enough to speak directly to those who understand.

The progression from confusion (“What brought you back?”) to decisive refusal (“I don’t want this anymore”) maps both personal healing and political awakening. The recognition that inconsistent treatment (e.g. Nazi permanent improvisation doctrine) is control, and that saying “enough” is de oppresso liber.

Translation

| جارا إيه؟ مش كنت ناسيني؟ | What happened? Hadn’t you forgotten me? |

| إيه اللي جابك تاني يا عيني؟ | What brought you back again, my dear? |

| أيوة زمان كنت حبيبي | Yes, once upon a time you were my love |

| بس خلاص دانا مش عايزة | But enough—I don’t want this anymore |

| أرجع لأ، فكر آه، سيبك لأ | Go back? No. Think? Yes. Let you be? No. |

| مش عارفة دماغي لفة | I don’t know, my mind is spinning |

| وأنا دايماً يا يا يا يا | And I’m always going ya ya ya ya |

| جنني، جنني | Drive me crazy, drive me crazy |

| على دقة ونص رقصني | You made me dance to your rhythm and a half |

| جنني، جنني | Drive me crazy, drive me crazy |

| قربه وبعده بيتعبني | Your closeness and distance exhaust me |

| يا حبيبي أغنيتي خلصانة | My darling, my song is finished |

| ما تعرفش تلعب معانا | You don’t know how to play with us |

| الموزيكا بقى تمشي إزاي | How does the music even flow now? |

| بس بتلعب طبلة ونای | You just play drums and flute |

| آه جنني | Ah, drive me crazy |

| يا معذبني | Oh, you who torment me |

| إيه ده اللي إنت بتعمل بيا | What is this that you’re doing to me? |

| يوم جايبني يوم ماخدني | One day bringing me close, one day taking me away |

| بس خلاص دانا مش عايزة | But enough—I don’t want this anymore |

Like the Beersheba Ruse carrying a carefully curated message to the Ottomans in 1918, followed by a daring stampede by Aboriginal horsemen to overwhelm machine guns and artillery, “Ganeni” calls upon reason with its rhymes. The British couldn’t directly confront Gaza fortifications, so they crafted a clever ruse to go around.

In regions where direct political expression is dangerous, art continues as the vehicle for truth. The song charts internationally in Arabic, promoting messages of resistence to oppression.

Related: هواجيس – Worries