The US used aircraft to drop explosives in Somalia, killing a large number of people. This abruptly has reminded us all of the existence of ongoing US military operations there, under the aegis of Africa Command (AFRICOM), and I see confusion in my social networks. Perhaps I can help explain what is going on.

Allow me to back up a few years to give some context.

The Shift from Covert to Overt Operations

US military European Command (EUCOM) leaders realized ten years ago they needed a more focused and local approach if expected to run “stability operations” in Africa. Do you remember in 2006 when the ICU (Islamic Courts Union) defeated CIA-backed warlords in Mogadishu? In response, the US special forces backed a 2007 Ethiopian invasion of Somalia to retake control and remove the ICU, as I wrote in posts here called “Ethiopia rolls 1950s tanks into Somalia” and in “Ethiopian invasion of Somalia“.

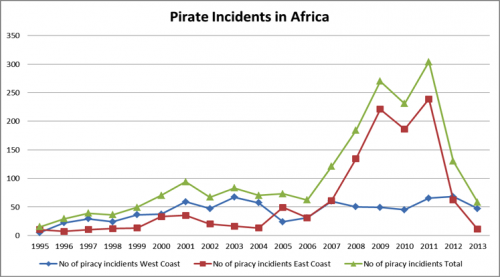

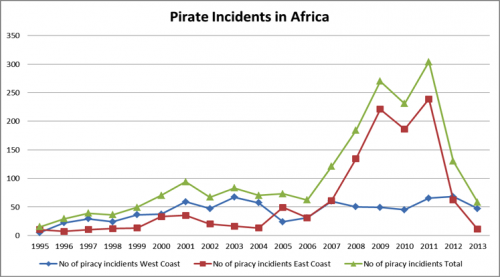

This public EUCOM “stabilization” effort, to use Ethiopia as a proxy military power after the CIA lost covert control, effectively created a huge sucking sound; a vacuum of leadership and instability (free market) was left behind after a neighboring state intervened. The ICU essentially transitioned into Al Shabaab at that time. Although that transition event might seem obscure, most Americans actually have heard of the piracy issues it generated. Unregulated seas and collapse of safe markets led to organized crime backed by Arab investors; the explosion of attacks became a major news story and headache in global shipping, as you can see in a simple SIPRI graph illustration of President Bush’s 2007 Foreign Policy results:

The question before US politicians back then was how to build overt military operations in the Horn of Africa, almost exactly like Britain had to decide in 1949, to push for state control while being considered light-touch state-building (aid) or at least state-support (self-defense) operation (mostly ignoring global piracy issues and wider regional market instability it would create).

Foreign Military Support for African States

EUCOM knew even before 2006 that the US needed a more focused regional approach in Africa to achieve its assigned policy aims. Africa obviously isn’t part of (post-colonial) Europe so change to a more focused regional resource was overdue. Thus, to formalize and better focus emerging intervention and military support policies for Africa, AFRICOM was created in 2008 under President Bush:

This new command will strengthen our security cooperation with Africa and create new opportunities to bolster the capabilities of our partners in Africa. Africa Command will enhance our efforts to bring peace and security to the people of Africa and promote our common goals of development, health, education, democracy, and economic growth in Africa.

This presidential declaration eight years ago of bringing peace to Africa might seem a long stretch from the very recent news of US warplanes bombing Somalia. Bear with me for another minute.

The mission of AFRICOM originally was described as cooperation and augmentation of African governments against destabilization; a mission of dealing with “failing states” rather than taking on war-fighting or “conquering state” objectives. This is of course a bit ironic, given how it rose from the ashes of Somalia invaded by Ethiopia. To be fair though AFRICOM being established under Bush offered the chance for a different future and more locally relevant options than under EUCOM. Although I’ve studied military operations on the Horn of Africa all the way back to the 1930s this major policy shift in 2008 is a good place to start looking at American reasons for being in Somalia today.

Policy Shift and the Acceptance of Foreign Military Support

Creation of AFRICOM was not without controversy at the time, as explained by FOX news.

Most Africans don’t trust their own militaries, which in places like Congo have turned weapons on their own people.

So “they don’t trust Africom, either, because it’s a military force,” Okumu [Kenyan analyst at South Africa’s Institute for Security Studies] said. There is also “a suspicion America wants to use us, perhaps make us proxies” in the war on terror.

AFRICOM initially was to take control and run an existing base in Africa, as well as support the increasingly wider regional military objectives. Aside from pushing a 2007 Ethiopian invasion of Somalia to bring down the ICU, US policy was following at least two prior initiatives: One, in 2002 a US military Combined Joint Task Force base was established in the Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA), staffed with thousands of military personnel. Two, by 2005 a “Flintlock exercise” among many African security forces was being led by the US across the Sahel region (from Djibouti to Senegal).

Thus it makes sense why some were worried that US operational bases with proxy combat missions could be a result. We may never know how AFRICOM was intended to roll out because, after Bush’s grand political hand waving about humanitarian missions and economic stabilization, Obama came into ownership in 2009 with different thoughts on foreign policy.

It seems to me the worries about intentions were well-founded. Obviously Bush already had been caught lying, or at least willfully ignoring truth, in order to invade Iraq. That alone should give everyone pause. His use of Ethiopia in 2007 appeared to similarly be a thinly-veiled destruction of Somali sovereignty to maintain CIA access for renditions and executions on foreign soil without declaring war. Bush foreign policy was so US-centric it raised concerns about, for lack of a better phrase, dumb imperialist thinking.

So in 2009 a new president came into ownership without the same legacy and policy baggage. Obama soon gave speeches that started a slightly different spin on US partnerships with African states:

When there’s a genocide in Darfur or terrorists in Somalia, these are not simply African problems — they are global security challenges, and they demand a global response.

A good indicator of where AFRICOM headed under the new US leadership was seen in operation Celestial Balance, as I wrote in 2010. Tactics changed under an Obama doctrine through more intelligent and less heavy-handed methods of “direct action”, a euphemism for unmarked black helicopters appearing suddenly and killing people identified as threats to America…ahem, I mean global security.

Obama would say privately that the first task of an American president in the post-Bush international arena was “Don’t do stupid shit.”

The difference was significant.

A former president believed evidence was an inconvenience and a latter president wanted carefully weighed and measured outcomes. Less fanfare, less flowery, clear and surgical operations, based on strong evidence, led to highly targeted missions, albeit without much outside review or transparency.

Then, rather than condemn the new US foreign policy doctrine of AFRICOM and US “actions” in Africa, Somalia’s new government warmed to the program and called for even more collaboration against threats.

In a series of interviews in Mogadishu, several of the country’s recognized leaders, including President Sharif, called on the US government to quickly and dramatically increase its assistance to the Somali military in the form of training, equipment and weapons. Moreover, they argue that without viable civilian institutions, Somalia will remain ripe for terrorist groups that can further destabilize not only Somalia but the region. “I believe that the US should help the Somalis to establish a government that protects civilians and its people,” Sharif said.

It appears, from my reading of the Somali perspective over time, we can not easily write-off AFRICOM as the proxy war engine it could have become. There have been no new American bases built. Instead we have seen state-building, or at least assistance in state self-defense, pointing in the direction of augmentation and support. We can criticize transparency, but so far we don’t have a lot of ground to call Obama’s “direct actions” policy a purely self-serving war using African states as proxies.

The Bush administration was right to heed EUCOM establishing new focus, creating AFRICOM; it appears only to have been wrong in how it thought about supporting intelligence operations and its disregard for economic impact. Hard to say whether Obama has been right, but it is likely not worse than before (no longer threatening sovereignty, no longer undermining regional economic viability).

Somalia, let alone the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), has continued talking about being a partner on global security efforts. This is unlike the 2007 Ethiopian invasion with US objectives front and center, aligning awkwardly with other nations or prodding them into going along also for self-interest.

The US currently is feted as a partner in regional Horn stabilizing missions rather than owner or operator. Local stability and growth policy using global partnerships isn’t an entirely awful thing, especially when we see China talking about and doing much of the same in its foreign relations for this region and throughout Africa.

Why An Air Strike?

Ok, so enough background. Back to the present tense, what’s with bombing hundreds of people?

According to a tweet by the BBC Africa Security Correspondent, Tomi Oladipo:

both Al Shabab & residents confirmed militants hit. Dispute is over death toll.

Everyone on the ground seems to agree casualties were militants and not any civilians. I have not seen anything contradicting this: militants massed in a training camp were preparing to graduate and execute a mission to undermine regional stability. The only major caveat to the reporting and news is Al Shabaab has been known to infiltrate news organizations to murder journalists it disagrees with; local reporting can be hard to gather.

I asked Paul Williams, Associate Professor at GWU and author of “War & Conflict in Africa“, if this strike could be seen as a prevention measure, given recent Al Shabaab attacks. He quickly confirmed that as true:

#AMISOM reconfiguring after Leego, Janaale & ElAdde to avoid a repeat.

If you’re familiar with those three references to Al Shabaab attacking security camps you easily can see why this strike to their camp fits regional conflict patterns, with the US serving to help local government forces maintain control and protect civilians.

With this in mind I would like to address four questions raised by Glenn Greenwald about the attack:

One.

Were these really all al Shabaab fighters and terrorists who were killed? Were they really about to carry out some sort of imminent, dangerous attack on U.S. personnel?

Yes, we see credible accounts of imminent danger, in the pattern of recent attacks, from an Al Shabaab militant camp. It almost could be argued that this attack was in response to those earlier militant attacks; a better self-defense plan was called for by local authorities (Somalia and Kenya) after those disasters. US personnel were in danger of attack by nature of working with the authorities targeted by Al Shabaab. We also don’t have details on the attack planned but it very well could have been similar to Westgate or Garissa University.

Two.

There are numerous compelling reasons demanding skepticism of U.S. government claims about who it kills in airstrikes.

Yes, big fan of skepticism here. At the same time, by all accounts and recent events, this appears to be a clear case of a military camp being destroyed to prevent terrorist attack later. BBC made the casualty type clear. Recent Al Shabaab operations, attacking Kenyans while in camp, should further erode skepticism around motive and opportunity of attacking militants while in their camps. I have not yet seen evidence civilians were in these camps. South Sudan, just for comparison, has been a completely different story.

Three.

We need U.S. troops in Africa to launch drone strikes at groups that are trying to attack U.S. troops in Africa. It’s the ultimate self-perpetuating circle of imperialism

This is lazy and shallow reasoning. If US troops left Somalia there would still be attacks by Al Shabaab on the authorities there. Whether you agree or not with supporting the local regime, it is not fair to say the only purpose of US troops is to act like a target for the premise of self-defense to attack US enemies. We have credible evidence that it goes beyond a proxy conflict, and the US is in fact assisting local authorities who are under attack. We can debate the integrity of a US-backed authority and their role in calling for assistance, yet it is clear Al Shabaab is a threat to far more than just Americans.

Four.

Within literally hours, virtually everyone was ready to forget about the whole thing and move on, content in the knowledge — even without a shred of evidence or information about the people killed — that their government and president did the right thing.

Surely I will be called an exception here, as I mentioned already I’ve studied conflict on the Horn for over two decades and have undergrad and graduate degrees focused on it, yet I do not find lack of interest to be true for the general population. There never has been more interest in this region than today.

This blog post was written because people were talking in general conversations about these killings. The fact that the story initially was brought up as a drone attack meant it drew a lot of attention. Conversations went on for hours just about the technical feasibility of drones to carry out such a large attack.

Granted we should be paying more attention. That seems like a great general principle. I am seeing more people pay more attention than ever before to issues and a part of the world that used to be obscure. Within literally hours everyone was asking questions about what happened, who really was killed, and why. It is actually quite a shock to see Somalia so much in the news and Americans digging immediately into the details, asking what just happened in Africa.

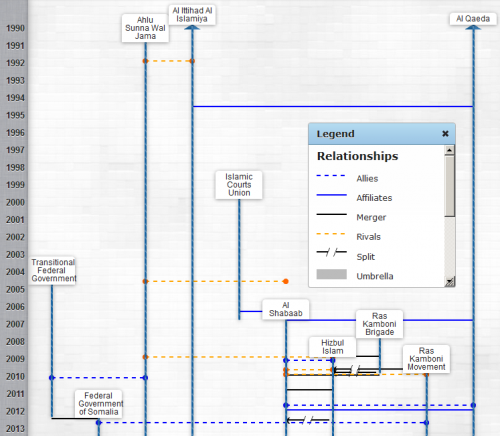

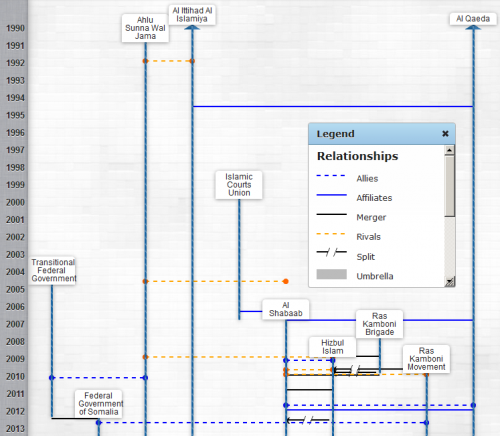

Updated to add a “mapping militants” project chart of Somalia, which better illustrates why power fractures and allegiances are complicated.