Charlotte, North Carolina, has a “Confederate” history marker that I noticed while walking on my way into meetings at Bank of America headquarters.

It is in need of major revision, if not removal.

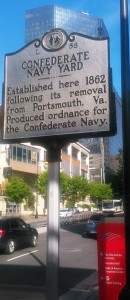

Let me start this story at the end. My searches online for more information eventually found a “NC Markers” program with an entry for L-56 CONFEDERATE NAVY YARD.

Closer to the end of the war…tools and machinery from the yard were moved from Charlotte to Lincolnton. Before the yard could be reassembled and activated in Lincolnton, the war ended. After the war the yard’s previous landowner, Colonel John Wilkes, repossessed the property, for which the Confederate government had never paid him. Where the Confederate Navy Yard once operated, he established Mecklenburg Iron Works. It operated from 1865 until 1875 when it burned.

Please note the very vague “the war ended” phrase in the second sentence.

This supposedly historic account seems to obscure the very simple fact that white supremacists lost the war they started to expand slavery.

I find saying “the war ended” to be an extremely annoying attempt to avoid saying who lost.

To make the problem more clear, compare the above L-56 official account with the UNC Charlotte Special Collections version of the same history:

The exact date of the formation of the Mecklenburg Iron Works is unknown, as is ownership of the firm until its purchase in 1859 by Captain John Wilkes. There is evidence, though, that the firm existed as early as 1846. The son of Admiral Charles Wilkes, John was graduated first in his class at the U.S. Naval Academy in 1847. Following a stint in the U.S. Navy, Wilkes married and moved to Charlotte in 1854. Two years after he purchased the iron works, the Confederate government took it over and used it as a naval ordnance depot. After the Civil War, Wilkes regained possession of the Iron Works, which he operated until his death in 1908. His sons, J. Renwick and Frank, continued the business until 1950, when they sold it to C. M. Cox and his associates.

So many things to notice here:

- Confederates appropriated a firm in their war to expand slavery, and possession was returned after they lost that war.

- There was a Captain John Wilkes, not Colonel, although neither story says for which side he fought. An obituary lists him as U.S. Navy and says he was active during Civil War

- Captain John Wilkes was the son of infamous Union Navy Admiral Charles Wilkes, who was given a court-martial in 1864. Was John, son, fighting for the North with father, or South against him?

- There is evidence these Iron Works were established long before the Civil War. NC Markers says “as early as 1846”. The Charlotte library says Vesuvius Furnace, Tizrah Forge and Rehoboth Furnace were operating 35 years earlier, with a picture of the Mecklenburg Iron Works to illustrate 1810.(1)

- Wilkes was not just “yard’s previous landowner”, he ran an iron works two years before the Confederate government took possession of it. Did he lose it as he went to fight for the North, or did he give it to help fight for the South? Seems important to specify yet no one does. In any case the iron works was pre-established, used during Civil War and continued on afterwards

The bigger question of course is who cares that there is a Confederate Navy yard in Charlotte, North Carolina? Why was a sign created in 1954 to commemorate the pro-slavery military?

Taking a picture of the sign meant I could show it to an executive business woman I met in Charlotte, and I asked her why it was there. She told me “Democrats put up that sign for their national convention”. She gave this very strangely political answer about the Democrats in her very authoritative voice while being completely wrong. And she both seemed opposed to the sign because of who put it up, yet in no way interested in taking it down. She ended with an explanation that there was no mention of slavery because (yelling at me and walking away) “CIVIL WAR WAS ABOUT TAXES, NOT SLAVERY. I KNOW MY HISTORY”.

I found this also very annoying. Apparently white educated elites in North Carolina somehow have come to believe Civil War was not about slavery. She was not the only one to say this.

What actually happened, I found with a little research, was the North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program started in 1935. They put up the signs, with no mention of Democrats or political conventions, as you can tell from the link I already gave at the start of this post.

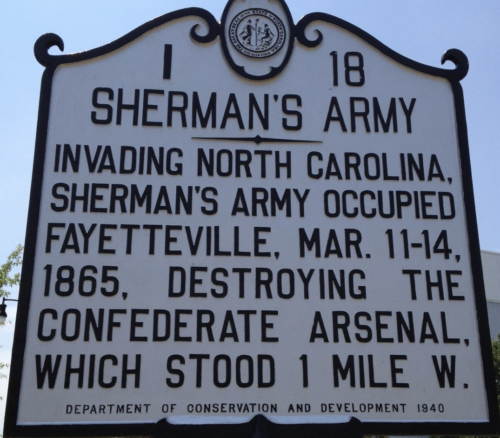

Here is the kind of one-sided “history” the program promotes, calling the preservation of the Union by its own forces an “invasion” and then “occupation”.

Historian pro-tip, you aren’t technically an occupying army when you still are in your own country, even if in an attempted secessionist territory. Otherwise we would still say today that American troops are invading North Carolina when they are assigned to Fort Bragg.

Speaking of Fort Bragg it was opened in 1918 (under racist “America First” President Wilson) and stupidly named after the Confederate General Braxton Bragg.

Bragg is said by historians to have been the worst tactician in the entire Civil War, causing major losses through incompetence that led to defeat of the pro-slavery forces.

Aside from perpetuating his racism, what possible reason would North Carolina have to name a U.S. Army fort after such a terrible enemy military leader known for losing battles let alone wantonly shooting his own men?

How could anyone in North Carolina been proud of Bragg?

Anyway, here is how the NC Markers program explains the official purpose of a CONFEDERATE NAVY YARD sign on the street:

For residents the presence of a state marker in their community can be a source of pride

Source of pride.

Honestly I do not see what they are talking about. What are people reading this sign meant to be proud of exactly? Is a failed attempt by pro-slavery military to create a Navy a proud moment? Confederate yards failed apparently because of huge shortages in raw materials and labor, which ultimately were because of failures in leadership. That is pride material?

What am I missing here?

The sign is dated as 1954. Why this date? It was the year the U.S. Supreme Court struck down “separate but equal” doctrine, opening the door for the civil rights movement. It was the year after Wilkes oldest surviving child died. Does a pro-slavery military commemoration sign somehow make more sense in 1954 (city thumbing nose at Supreme Court or maybe left in will of Wilkes last remaining child) than it does in 2016?

A petition at the University of Mississippi to change one of their campus monuments explains the problem with claiming this as a pride sign:

Students and faculty immediately objected to this language, which 1) failed to acknowledge slavery as the central cause of the Civil War, 2) ignored the role white supremacy played in shaping the Lost Cause ideology that gave rise to such memorials, and 3) reimagined the continued existence of the memorial on our campus as a symbol of hope.

[…]

From the 1870s through the 1920s, memorial associations erected more than 1,000 Confederate monuments throughout the South. These monuments reaffirmed white southerners’ commitment to a “Lost Cause” ideology that they created to justify Confederate defeat as a moral victory and secession as a defense of constitutional liberties. The Lost Cause insisted that slavery was not a cruel institution and – most importantly – that slavery was not a cause of the Civil War.

Kudos to the Mississippi campaign to fix bad history and remove Lost Cause propaganda. The North Carolina sign’s 1950s date suggests there might be a longer period of monuments being erected. When I travel to the South I am always surprised to run into these “proud” commemorations of slavery and a white-supremacy military. I am even more surprised that the residents I show them to usually have no idea where exactly they are, why they still are standing or who put them up.

Anyone who knows me well knows I walked into Bank of America and at the start of the meetings demanded an explanation for the sign outside. The response I heard was “what sign, never seen it” followed after the meeting by a call from someone asking how dare I mention the sign in a business meeting.

My response? How dare you put that sign in front of my meeting and tell me I can’t talk about it being a bad one.

At the very least North Carolina should re-write this sign to be accurate, if they can’t do the more obvious fix of removing it.

Here is my helpful suggestion:

MECKLENBURG IRON WORKS: Established here 1810. Pro-slavery militia in 1862 seized the works in a failed attempt to supply a Navy after their defeat in Portsmouth, Va. Liberated from occupation 1865.

That seems fair. The official “essay” of the NC Markers really also should be rewritten.

For example NC Markers wrote:

…in time it began to encounter difficulty obtaining and retraining trained workers

Too vague. I would revise that to “Southerners depended heavily on immigrants and Northerners for shipyard labor. As soon as first shots were fired upon the Union by the South, starting a Civil War, many of the skilled laborers left and could not be replaced. Over-mobilization of troops further contributed to huge labor shortages.

NC Markers also wrote:

…given its location along the North Carolina Railroad and the South Carolina Railroad, it was connected to several seaboard cities, enabling it to transport necessary products to the Confederate Navy

Weak analysis. I would revise that to “despite creating infrastructure to make use of the Confederate Navy Yard it had no worth without raw materials. Unable to provide enough essential and basic goods, gross miscalculation by Confederate leaders greatly contributed to collapse of plans for a Navy”

But most of all, when they wrote “the war ended” I would revise to say “the Confederates surrendered to the Union, and with their defeat came the end of slavery”.

Let residents be proud of ending the pro-slavery nation, or more specifically returning the Iron Works to something other than fighting for perpetuation of slavery.

So here is the beginning of the story, at its end. Look at this sign on the street in Charlotte, next to Bank of America headquarters:

(1) 1810 – Iron Industry screenshot from Charlotte – Mecklenburg Library